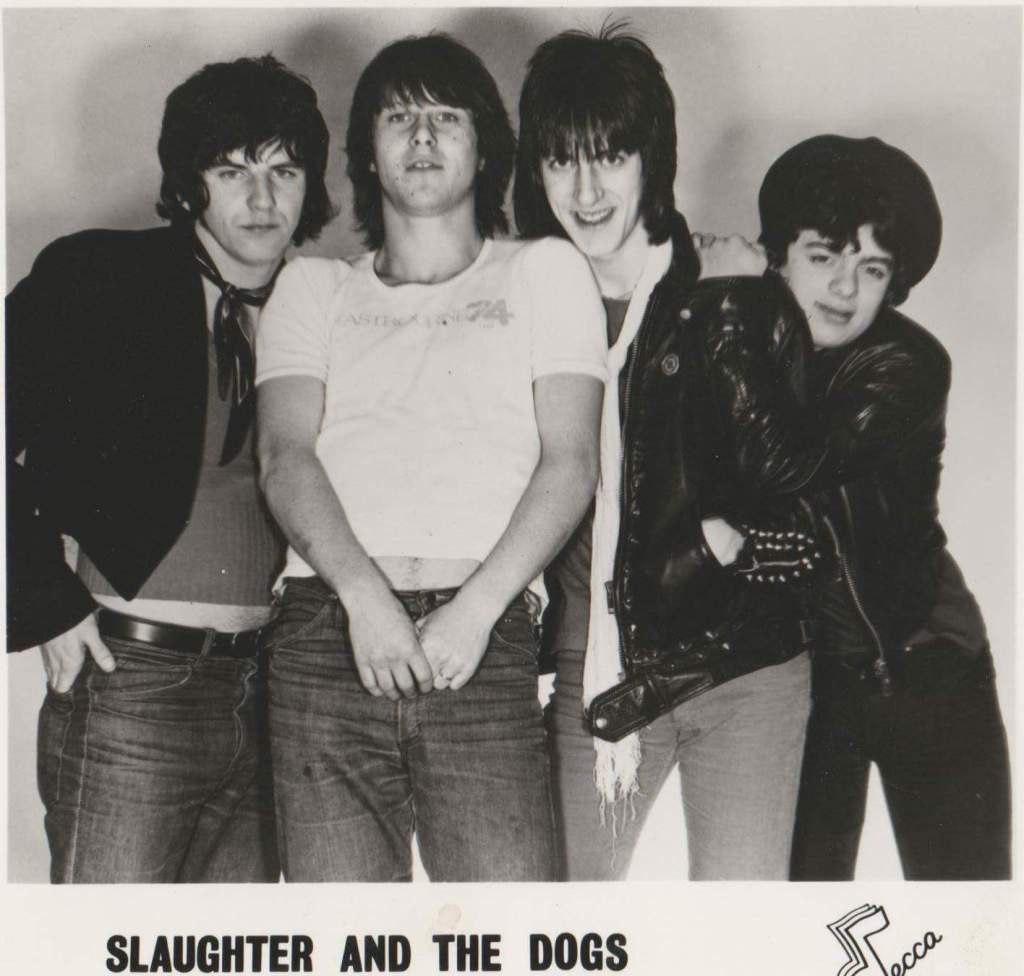

This interview feels special to me on several counts. First, I caught up with Wayne Barrett during what he says is his farewell tour under the Slaughter and the Dogs banner, closing exactly 50 years of this seminal punk outfit’s history. Second, Wayne chose to play the band’s final dates in my adopted homeland, Italy – a country he feels a special connection to (the band’s last album even bore an Italian title).

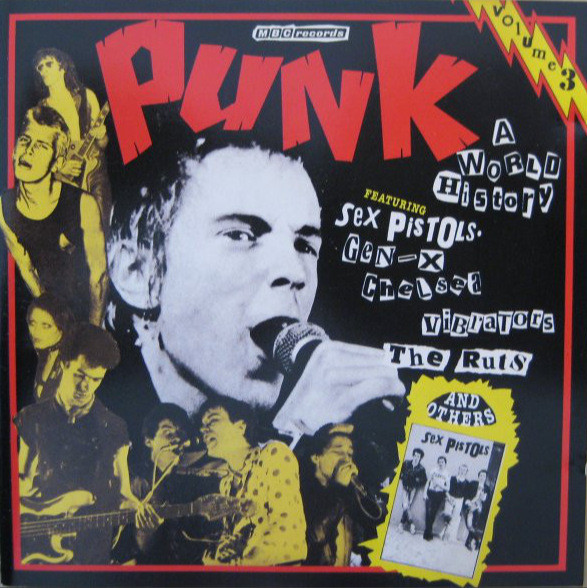

Third, it’s December, and with my birthday approaching, I’m reminded of the gift I received on my fifteenth: a record called Punk – A World History Vol. 3, which ranks high among the albums that shaped my taste in music. Part of a dodgy bootleg compilation series, it introduced me to a handful of ‘second-tier’ – but actually more enjoyable – figures of the original punk wave, such as The Boys, Chelsea, and of course Slaughter and the Dogs, who remain among my all-time favourites. Sitting somewhere at the intersection of bootboy, glam and punk, they were in some ways the perfect band.

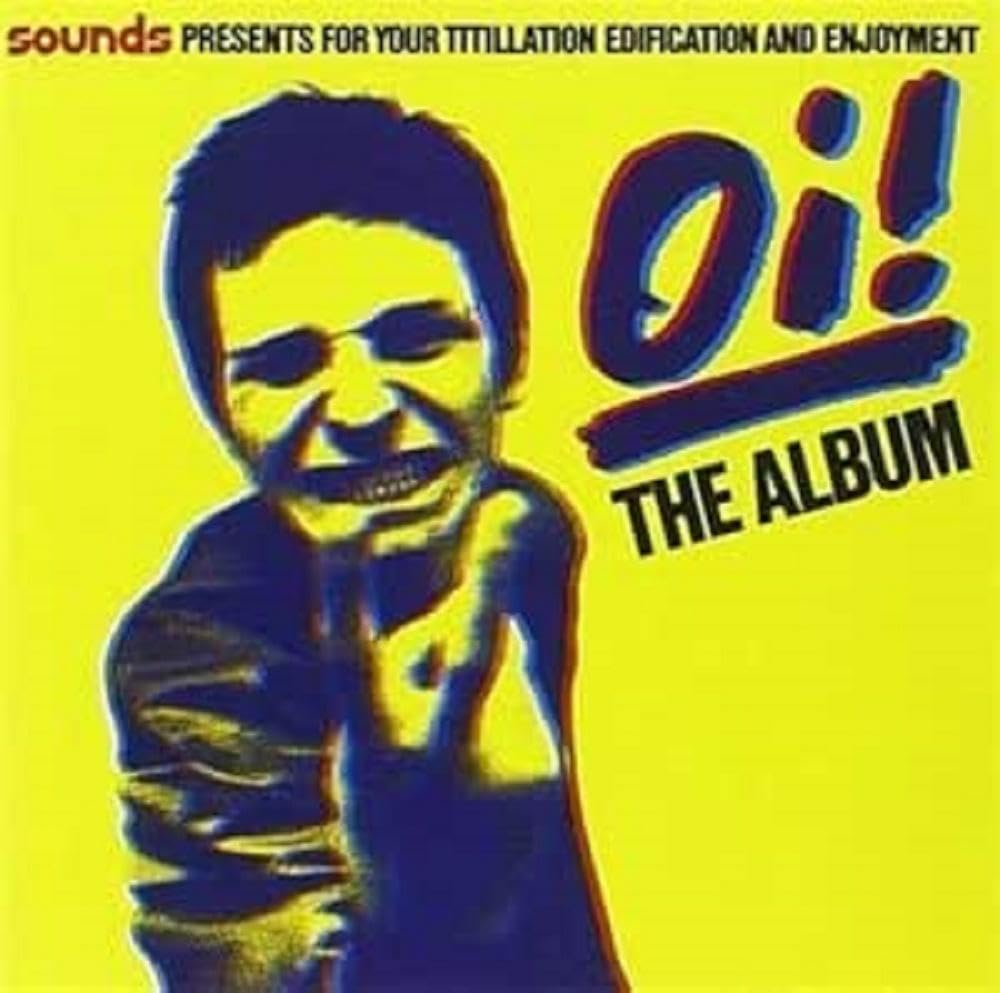

In the skinhead world, of course, the band is best known for their inclusion on Oi! The Album with ‘Where Have All the Boot Boys Gone’ – a 1977 single that helped put skins back on the map and retrospectively gave the band a sort of proto-Oi status. “Wearing boots and short haircuts, we will kick you in the guts” have got to be some of the greatest opening lines ever – not even The Last Resort managed to top them.

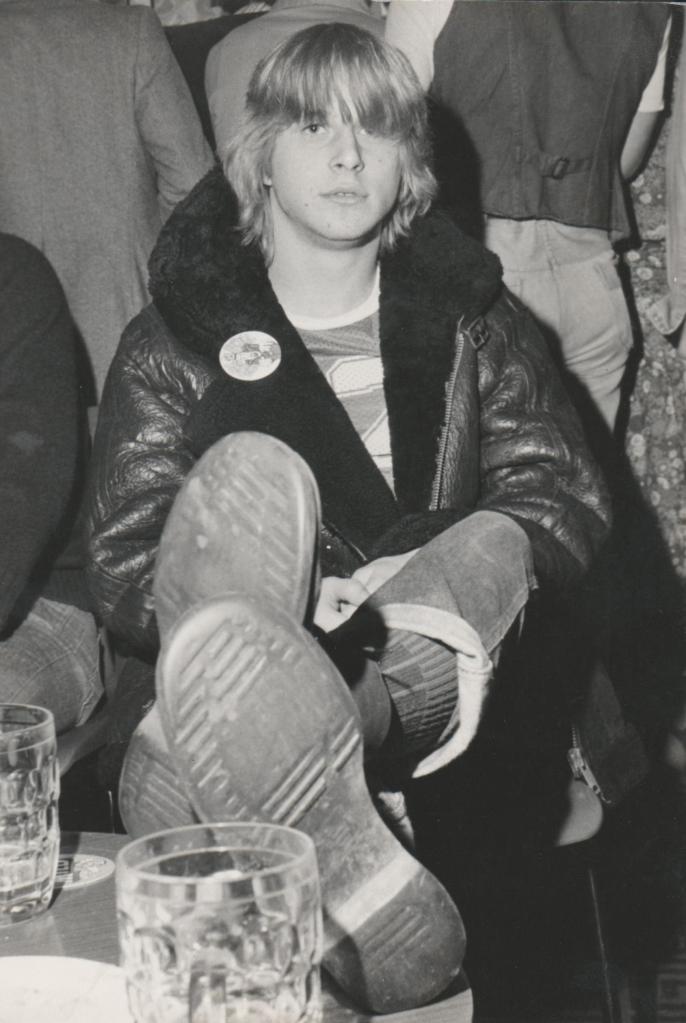

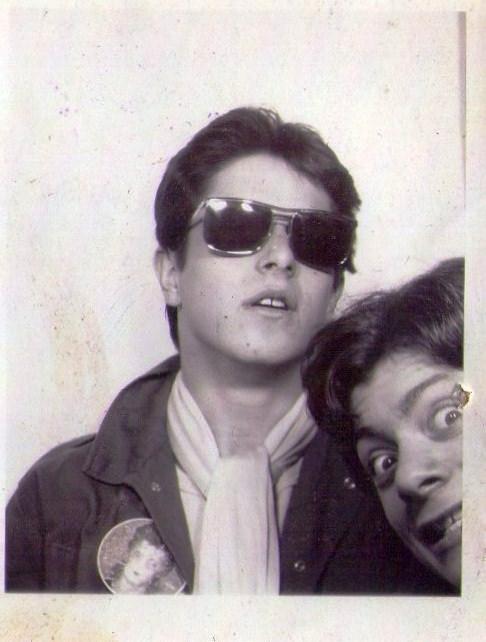

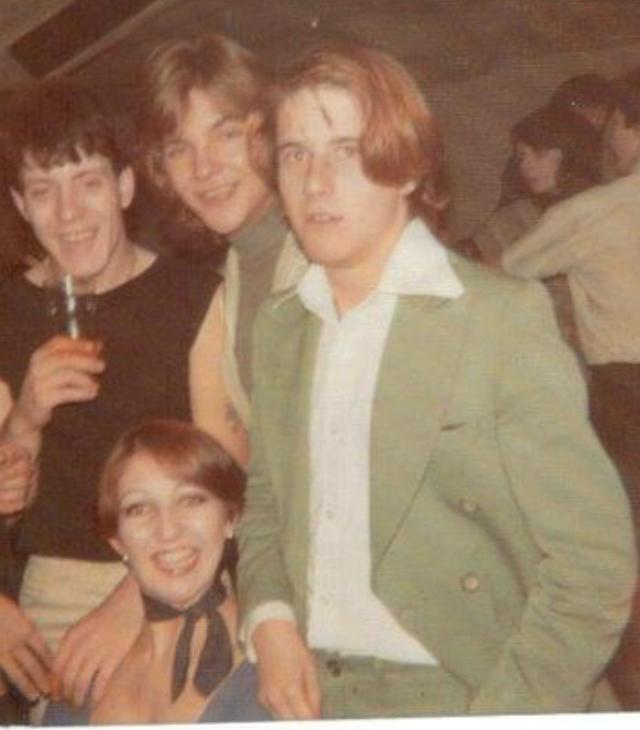

We spoke about the different stages of band founder and lead vocalist Wayne’s life: as a young bootboy; as a Bowie boy cutting his musical teeth at the tail end of glam rock; and as a Manchester council estate kid riding the first wave of English punk.

Many thanks to Wayne’s lovely wife and manager Erin for making it all possible!

Matt Crombieboy

Hi Wayne, I really enjoyed your gig in Bologna – I was pogoing like I was 16 again.

Good to hear that, I like putting a smile on people’s faces. I’m a bit knackered, but I had a good time.

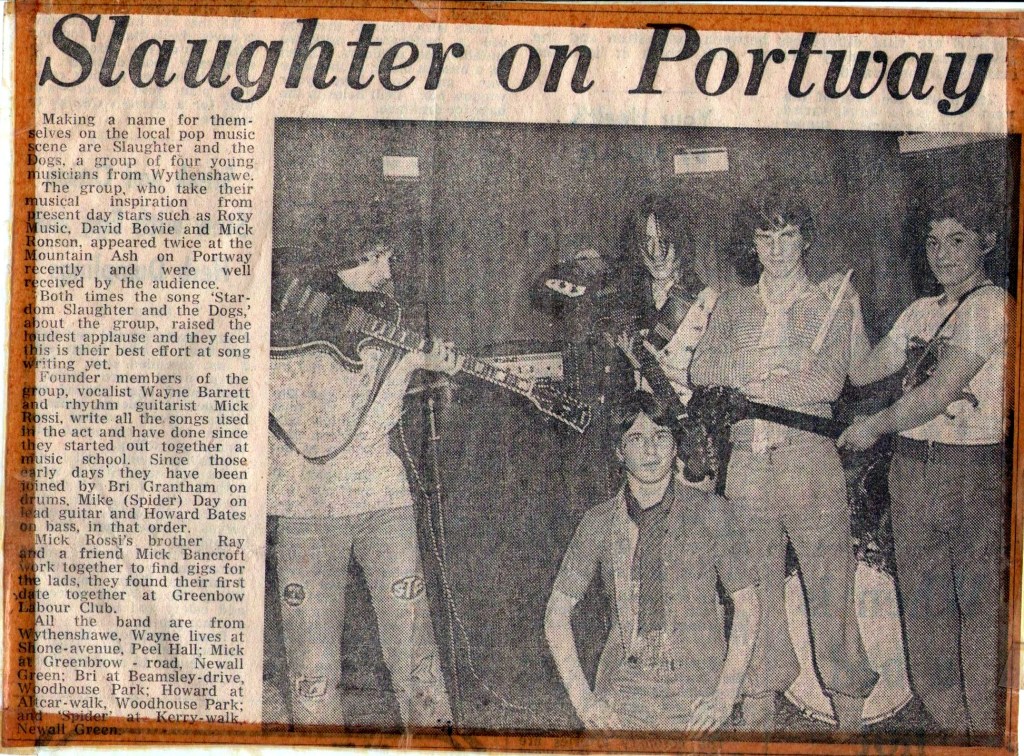

Let’s go back to the start. You first met Mick Rossi at Sharston High School when you were 15, right?

Exactly. I’m a year older than Mick. I met him because a mate said he was a massive Bowie fan, and I thought ‘Right, nobody knows more about Bowie than me’. So I went to test him in the schoolyard. I gave him a bit of stick, asked a few Bowie questions, and he got them all right – I was impressed.

He asked what I did at school, and I told him I played double bass. I’d been at it a couple of years, spent most lessons playing it. I asked if he fancied playing with me. Mick jumped at the chance – got him out of the other lessons. He was small then, so all you’d see were his arms around the bass, not the rest of him. I said, “Maybe try the guitar instead.” Next thing, he got his mum to buy him a Stratocaster, and that’s how it all began.

You grew up in Wythenshawe in Manchester, which was then Europe’s largest council estate.

It was massive, absolutely huge. After the war they built loads of prefabs and moved in Irish families, Jamaicans, anyone who was poor really – all sorts of social cases. It wasn’t a ghetto, but it was socially segregated enough to feel like one.

The New York Times described the estate as an “extreme pocket of social deprivation and alienation”, but that was in 2007. Was it already like that back in your day?

Well, let’s just say things were different. The world’s more individualistic now, people look after themselves first. Back then, even if we didn’t have much money, there was more solidarity. You respected your neighbours, people looked out for each other.

You mean there was a proper working-class community?

Yes, exactly.

Wythenshawe has also been described as the skinhead capital of the North.

It was, yeah. Where we grew up, people felt respect and fear at the same time. The fear came from lads like me and my mates – if you didn’t follow the laws of Wythenshawe, you got burned. I terrified a lot of people, but it earned respect. When we skinheads said something, people might not like us, but they couldn’t ignore us. Sure, there was a bit of bullying involved.

But when people today say all skinheads are nazis, they’re wrong. Back then, the skinheads, the bootboys, we were socialists. We defended the poor. The nazi stuff came later because politicians made it so. They used skinheads as security, built them up, promised them a future. Many had no future, so they jumped at it – a real shame. In my day it was about unity. We weren’t angels, but there was no racial discrimination.

How old were you when you became a skin?

About 12 or 13 – I was well into it, and into the music. Slade, loads of rocksteady, Motown. If you went to the pub, the music on the jukebox would be Motown.

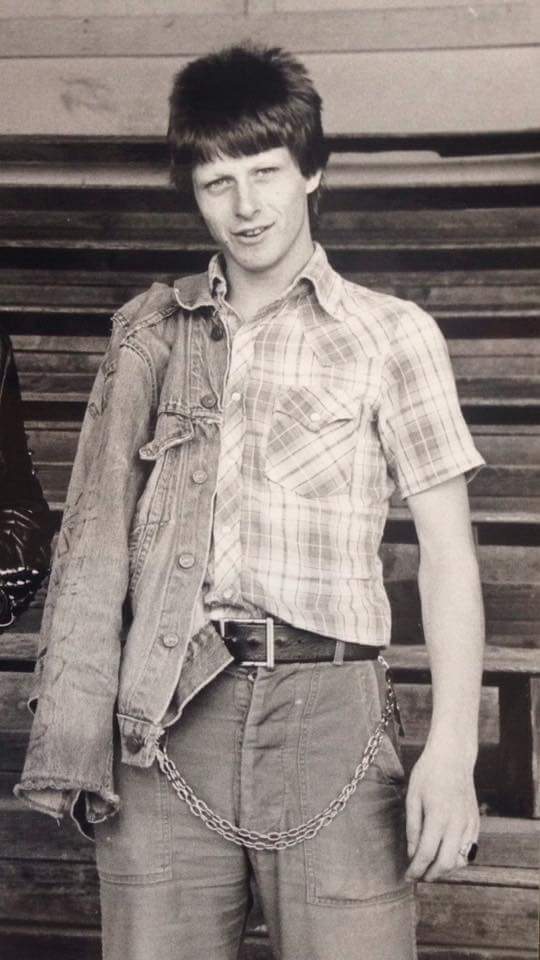

What were you wearing back then?

I was a skinhead, but more of a bootboy. Bootboys wore parallel jeans with their boots. Mine were monkey boots because they were cheaper than Docs. Actually, my last couple of pairs of Docs were badly stitched, so I’ve gone back to the old East European monkey boots, made in the Czech Republic. I’ve got two pairs now: one oxblood, one black.

You’re a scooterist now, right? Last time we met, you wore a parka covered in patches.

Yes mate, I am. Started that way back, I think around ’73 or ’74, when skinheads were drifting into glam. Loads of skins in Manchester had scooters then. We were stealing scooters, taking them apart, then rebuilding them. I like Vespas too, but my real love’s still the Lambretta.

Your iconic skinhead song, ‘Where Have All the Bootboys Gone’, mentions “Hammy, Jacko, Boots and John”? Who were they?

Real lads I hung out with. Hammy and Jacko were twins. We used to go to Stretford End together [the ‘lively’ west stand at Old Trafford, home of Manchester United]. One of them went to my school. John we called Johnny White Boy. We just hung out together, caused a bit of trouble.

Are you still in touch with any of them?

Nah. I last saw Hammy about 25 years ago when we were doing the Beware Of… album.

The song says: “Now it’s been five years or more, I’m a skin, I don’t know what for. I must move, move or die”. Was that autobiographical?

Yeah, completely. It was me talking to myself. When I was still at Sharston, I got caught doing something I shouldn’t and ended up in front of the headmaster. He told me I’d either end up in prison for life, shot dead in a robbery gone wrong, or dead in an alley with a needle in my arm. That was the future he painted for me.

What saved me was my music teacher. He saw me messing about on the piano in the assembly room. I couldn’t play properly, but he noticed I was trying to find harmonies and patterns. He said he was looking for a bass player for the orchestra, so I started that.

I just refused that bleak future he’d laid out for me. I pushed harder into music because I knew football wasn’t going to happen. I loved playing, but I didn’t have the talent. Back then, it was sport or music that could get you out.

When I was 15, three-quarters of the girls in my class were pregnant. You had one year left – at 16 you were out, and that was it. You were basically condemned to a no-life. It was mad.

Fast-forward a year or so and you’re in a band with Mick.

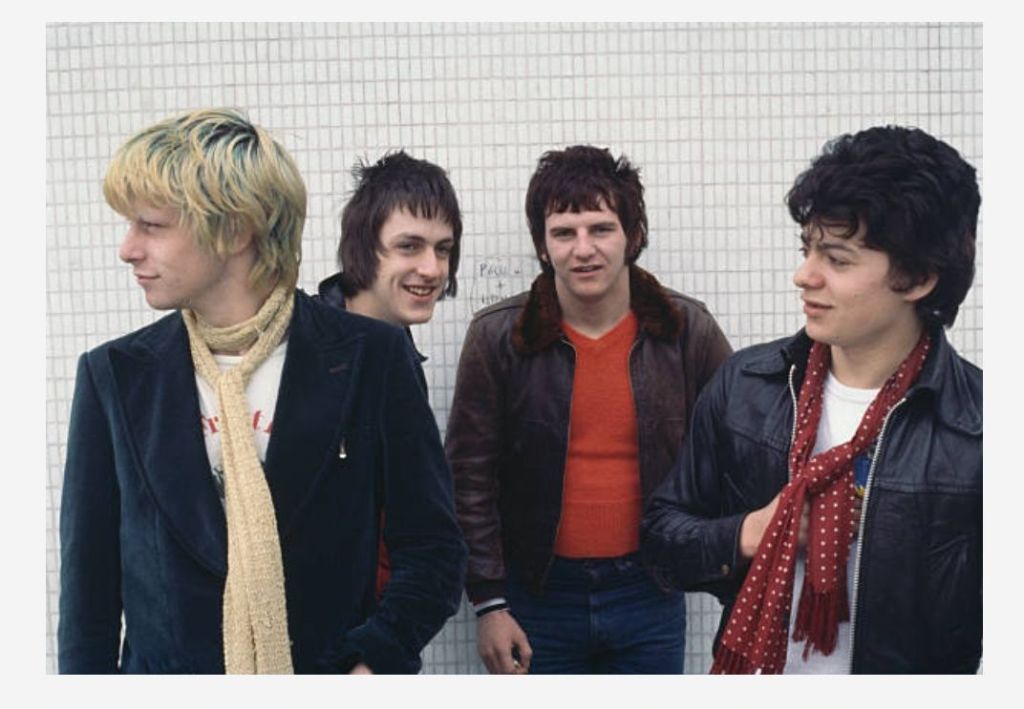

1975, yes. The name Slaughter and the Dogs was something I made up last minute before a gig. It came from Mick Ronson’s Slaughter on 10th Avenue and Bowie’s Diamond Dogs.

You were proper Bowie boys?

Definitely. We saved up and went to London to visit Bowie hangouts, hoping to see him. We even played songs from Space Oddity on the tube for a few quid. And we met Bowie’s first manager, Ken Pitt. We knew Bowie still visited him now and then, so we hung around his house in Manchester Square. One rainy day he came out and invited us in.

Pitt was very refined, and we were just scruffy Manc bastards. But he was very nice. His place was full of memorabilia – he’d managed Bowie, Long John Baldry, even Sinatra in England. I asked him to manage us, and he said no. I told him, “Well, one day you will” – and a few years later, he actually did.

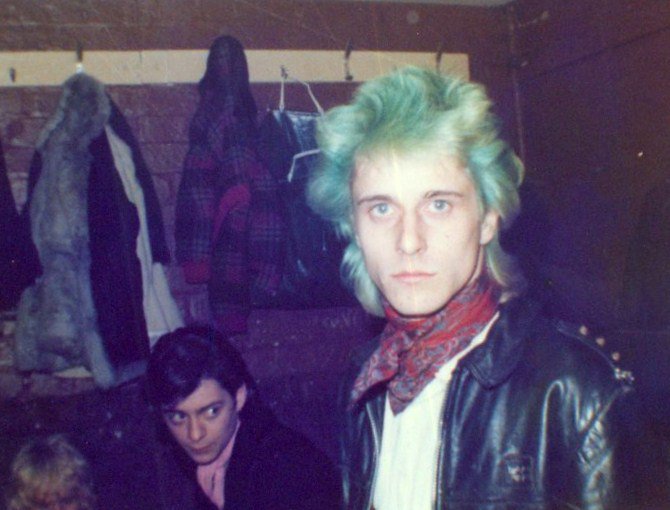

Did the Bowie boy look cross over to the terraces as well?

Oh yes, definitely. When you went to see Manchester United, you’d see Bowie boys there too. I had red hair, green hair, blue hair – kept changing it all the time. Once I dyed it green because my school had complained about my hair. Green matched the Sharston High uniform, so I told them it was school colour – that’s how I got away with it (laughs)

Where were you getting those colours so early, years before punk?

I worked part time as a colourist in a hairdresser’s. Bit of a pretty boy, the older ladies tipped me well.

Were you also into the American trash glam stuff, like the New York Dolls?

We didn’t have access to the American scene. Closest we got was Alice Cooper on TV, who was more horror than glam. Today, you click and it’s all there on Amazon, but back then you had to physically move to hear anything. We didn’t get to hear the New York Dolls until much later.

Fair enough. Did you have any particular influences or idols in terms of singers when you started out? Because you’ve got this punk snarl, but sometimes you hit those high notes punk singers don’t normally do. Like in ‘The Bitch’, where you go “But I couldn’t mend our love…” Where does that come from? Is it heavy rock, soul, or what?

It’s a bit of everything, really. I refused to be boxed into one genre. The only thing I couldn’t pretend to enjoy was free jazz, but I’d listen to everything else. I still believe today that creativity comes from accidental mixes of different art forms.

As for ‘The Bitch’, it was the B-side of Cranked Up Really High. Both songs share the same tonality because we worked with Martin, who knew his stuff. He asked us to listen to some records before the studio sessions and give him our feedback. One Jamaican reggae track had this rich trombone tone, and I thought: this should be a vocal tonality! That’s what inspired the EQ on the vocals and the “na na na” bit in ‘Cranked Up Really High’. The studio had this acoustic crackle that worked beautifully.

Some of your earliest recordings from 1975 were later released on the EP It’s Alright. Were these songs typical of your glam-era sound?

Well, the recording date was a lie (laughs). Those recordings were made when we signed to Decca. Our manager Ray sold them to TJM, who released them even though we were under contract. People thought they were pre-punk, but they were recorded at the same time as the first album.

But they were old songs you’d written in 1975, weren’t they?

Yeah, ‘Edgar Allan Poe’ and ‘Twist and Turn’ were early songs from 1975. But the other two, ‘It’s Alright’ and ‘UFO’, were basically just studio blues jams.

You played ‘Edgar Allan Poe’ at your Bologna gig – a nice surprise to hear such an early song. That one’s clearly pre-punk, with the guitar workout in the middle, and quite gothic too.

You see, in the early years, I was a proper bookworm for poetry: Ginsberg, Kerouac, Burroughs. Always drawn to the improbable. Edgar Allan Poe, House of Usher, that sort of thing, where the ending would surprise you. ‘Edgar Allan Poe’ came from that time. I’d wander round graveyards with green hair, reading or writing. People thought I was mental and left me alone.

So you were an early goth of sorts. Do you recall the first gig that you played with Slaughter and the Dogs?

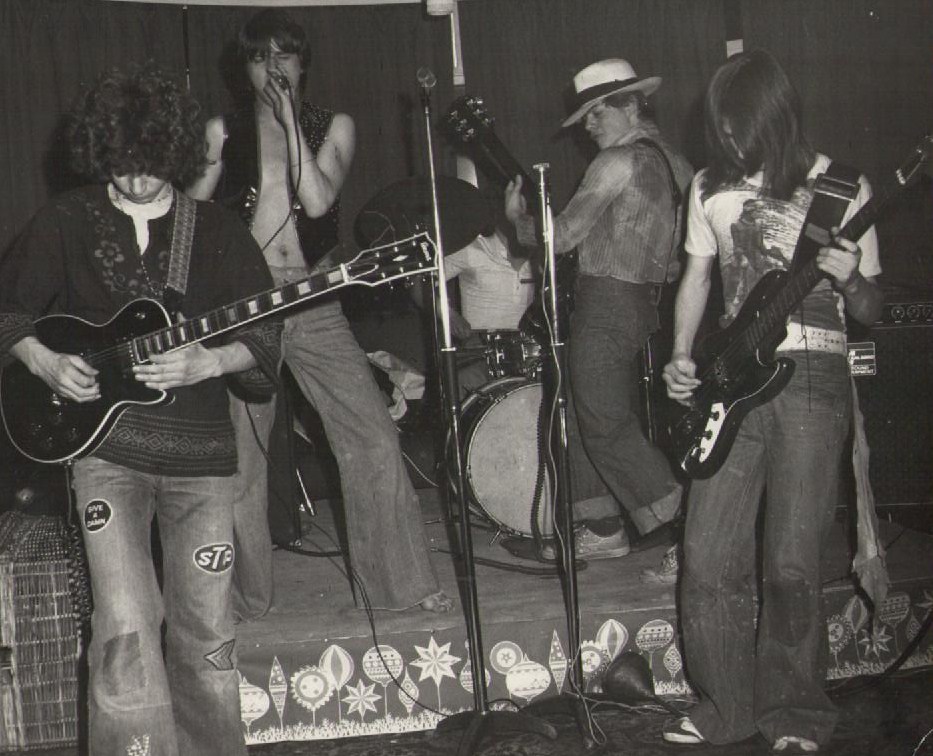

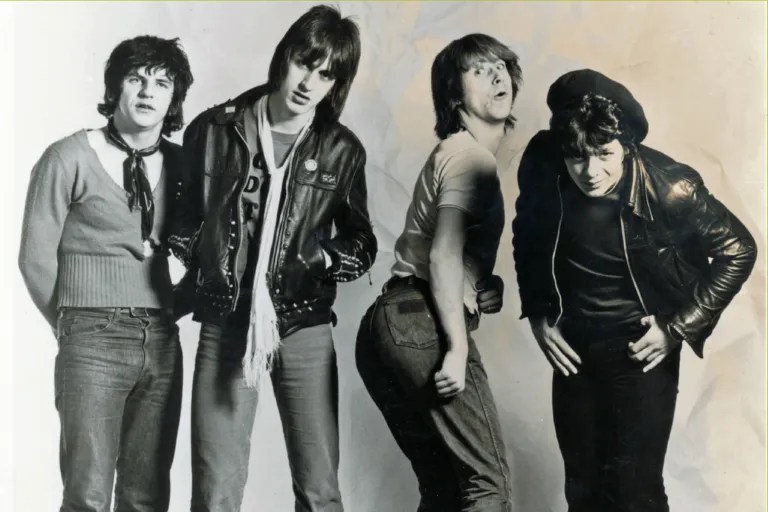

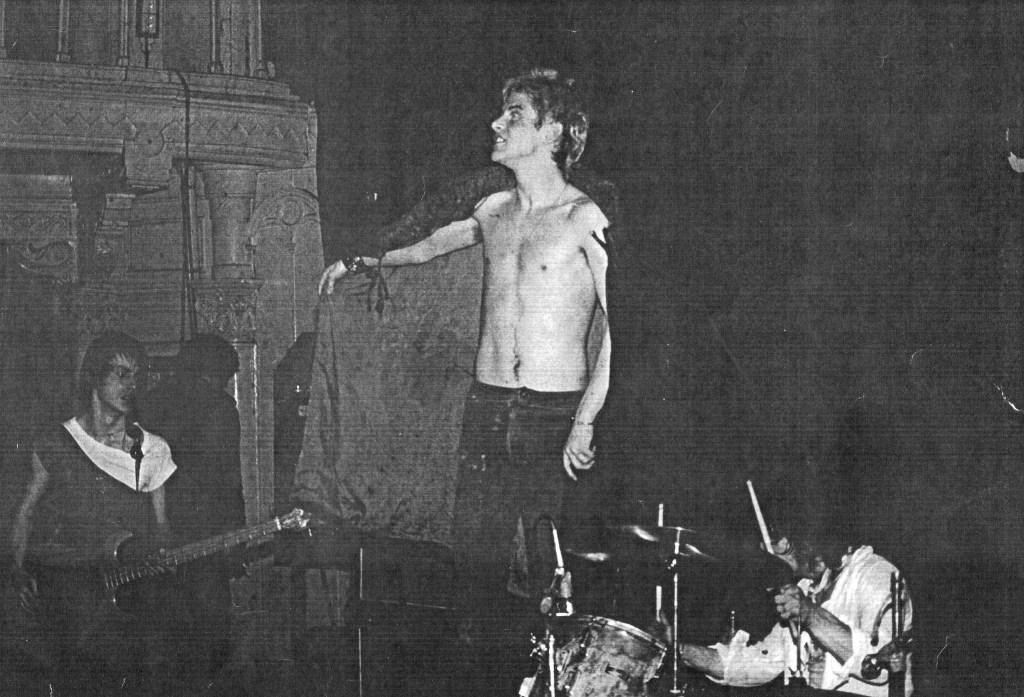

Yeah, March 1975 at the Greenbrow Social Club – a proper working men’s club full of old folk [on Greenbrow Road, Newall Green, Wythenshawe – Editor]. We went on like we were Bowie and Ronson. We were a five-piece then, with Mike Day on lead guitar.

Who were your audiences in those early pre-punk days?

Mostly kids from the estate. Our first shows drew 10–50 people, but soon we were playing to around 300. That’s why the Sex Pistols wanted us to open for them in Manchester – they’d only played to 14 people two months earlier and needed a bit of a bounce, and we already had a following.

How did that invitation come about?

Howard Devoto and Pete Shelley from the Buzzcocks came round to my parents’ house with our manager, Ray. They asked if we’d fancy playing with a band called the Sex Pistols. There was no internet, hardly any info about them in Manchester, but we said yes. They told us about their manager, who’d previously managed the New York Dolls. They seemed impressed, but I thought, “New York who?” – never even heard of them. The only American band I followed then was The Runaways.

Neil Spencer later compared us to the Ramones, but at the time I didn’t understand the Ramones’ significance. Today everybody claims they had the records, but most didn’t. Getting American imports like the Ramones was near impossible back then – same as with the Dolls a few years earlier. People love to say they had all the Dolls records from the start, but it’s just not true.

The Sex Pistols gig you’re talking about is the famous one at the Free Trade Hall, no?

Yeah, and I tell you what: I could fill Bingley Hall twice over with the number of people who claim they were there. Everybody says they went. Well, they didn’t. There were 385 people. I know because my mum was on the door with a clicker. Out of the 380-odd, 350 were kids from Wythenshawe – our fan club. The rest? Whoever they were, probably from Salford or somewhere. In fact, there was a big fight because some Salford lads turned up, and we knew exactly who they were. Salford, Manchester, Wythenshawe – they don’t get on. It’s like Marseille and Paris.

So what did you make of the Pistols? Was it a game-changer for you?

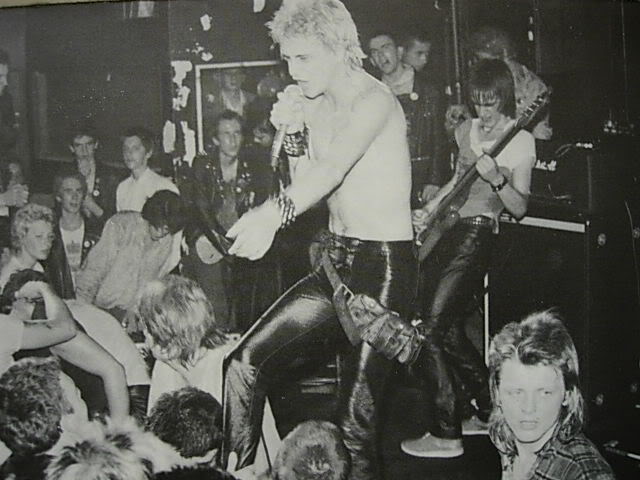

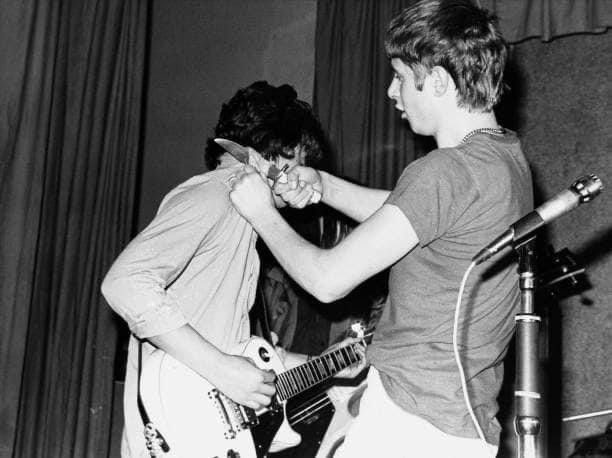

Oh yeah. We’d gone on stage still wearing the glam stuff, satin and all that, but I already had the attitude. We were kind of glam, but we kicked arse. After the Pistols, Mick, Brian, and I all thought, that’s attitude – we were blown away.

After the show, I spoke to Martin Hannett. He said, “Wayne, that was good. But you have to drop the satin and shiny stuff and just be yourself. You’ve got attitude. The clothes you wear in the street are exactly what you should be wearing on stage.” I thought, you know what? He’s right. I said, “I’m living a dream, I want to be David Bowie. But actually, I should just be myself”.

Some say Slaughter and the Dogs were just a glam band that jumped on the bandwagon when punk came along.

We couldn’t have jumped on any bandwagon because it didn’t exist. There were the Pistols, but nobody else. History makes it all look neat and ordered, but in reality punk was something new every day. It was still developing, becoming something. There were no rules. You have to remember, we started a year before it all kicked off.

Yes, of course there were the Sex Pistols, and later The Clash. But in April 1976, The Clash were still rehearsing in garages in London – they hadn’t even done a gig yet.

How did the press react to your show?

A local journalist from the Wythenshawe Express wrote a small piece about us. But because we came from Manchester, the London press wouldn’t touch us. We got coverage in the Manchester Evening News and other local papers, but the big music papers – Sounds, New Musical Express – were all London, Fleet Street-based, and they just ignored us.

But by ’77, you were playing in London and even appeared on the The Roxy London WC2 compilation. Did you move to London at that stage or were you just playing there?

No, we were just playing there at first. We only moved a couple of years later, in early ’79. But I left the band shortly after.

Being council estate kids from up north, how did you feel in London’s fashionable punk scene? Were you accepted?

They hated us. 99 percent of the London musicians were poseurs – more mannequins than musicians. All about the image, wearing immaculate £800 leather jackets, but the music was often terrible. The only lads we got on with were Cock Sparrer, who were signed to Decca as well, and Little Rooster, which Gary Lammin of Cock Sparrer started a bit later. I’ve stayed friends with Gary to this day because we have the same mind – was only on the phone to him last week.

As for the London music scene, I’ve always refused to bow down to the system. Managers and record companies tried to make us look commercial, but I wasn’t changing my music. Politically too, you have to be a certain way to get on media or TV. I’ve always refused that. Punk’s about real freedom of expression – not waiting for a journalist with a camera so I can punch somebody for a photo. That’s not me.

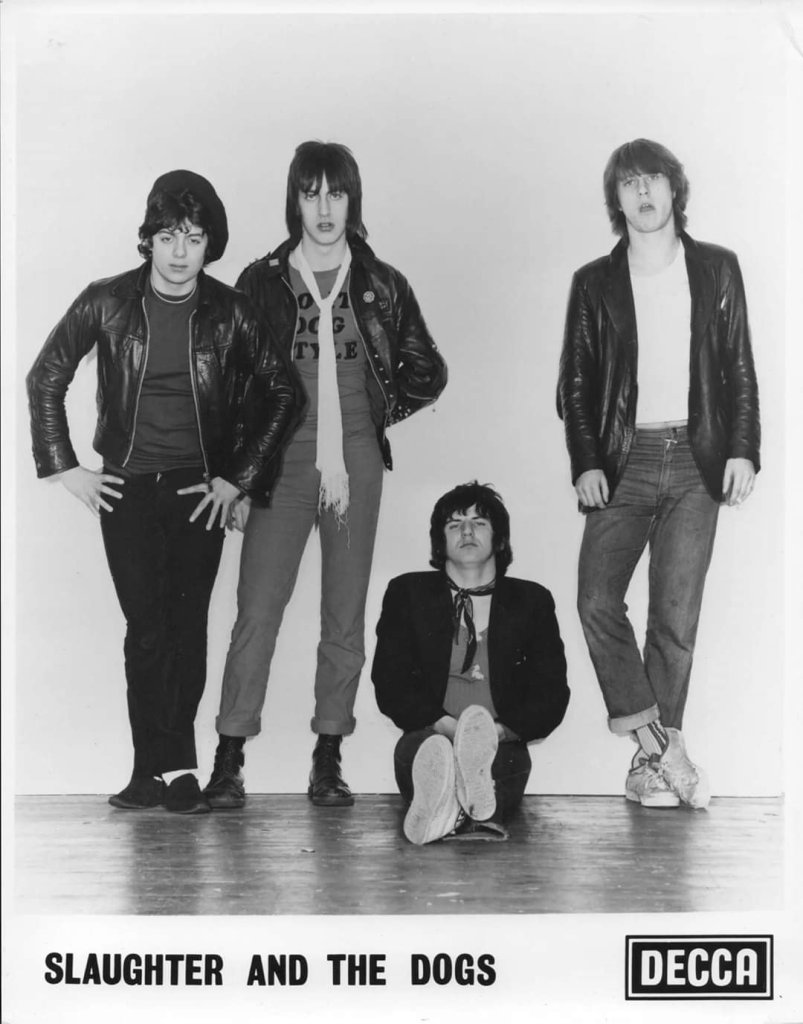

Decca was notorious for not promoting their bands well. For some reason, they published Cock Sparrer’s first album only in Spain, for example. How did they handle you?

Decca had big names – The Moody Blues, the Rolling Stones, Thin Lizzy – but they hadn’t signed a new band in nearly a decade. When they bought us – because that’s what they did – they thought they were getting a young band with some rock ’n’ roll attitude. They even bought up Rabid Records, our independent label we’d started with Tosh Ryan in Manchester.

They told us, “Whatever you want, you can have”. And as four hooligans, we took that literally – throwing money out the window, ordering champagne, living it up. They didn’t care, because they’d just deduct it from our royalties. Only one person from Decca ever came to see us rehearse; the rest stayed in the offices. They’d all been selling carpets or cars the year before, and now they were music industry people. Decca were a decade behind, what I called the ‘Stonehenge record company’.

Nick Tauber, our producer, was good to us – but he wasn’t punk or underground. He’d just nod along and cheer, “Rock ’n’ roll, woohoo”, which was fine, but that was the extent of it.

In 1979, Slaughter and the Dogs split up for the first time. You left for France to live with a girl. Mick Rossi commented later, “Our egos were getting bigger. Wayne and I had this rivalry. We were both guilty. Naivety played a massive part in the split”. What would you say about that?

I’d say he was right to some extent. Our egos were growing, and there was rivalry between us, but outside influences played a big part too. Friends, social circles – they started pulling us away from the band. I take some responsibility, but it was all part of learning.

How much did money factor into the split?

Quite a lot. We realised that money was disappearing, and the record deal was exploitative. The way royalties and advances were structured, you’d have to sell a million records to earn £100. I mishandled royalties, but it opened my eyes to how the industry really worked – spending, deductions, and withheld advances were all designed to benefit the label, not us.

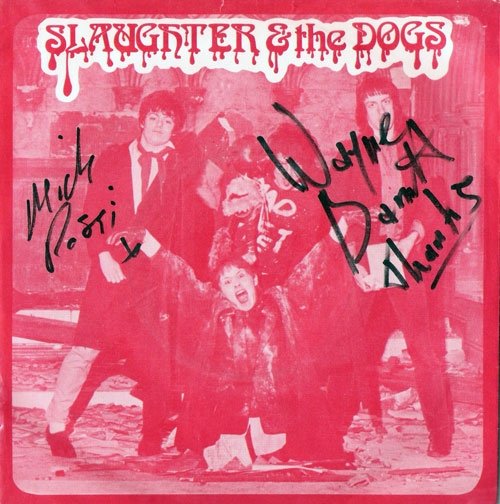

But you came back briefly and recorded the single You’re Ready Now with the band, right?

Yes, I came back after speaking to Mick. I was ready to stop the band – it was mine, after all, my name, my creation. They tried to keep it going, but for me, it was over. Mick asked if I’d give it another go. I agreed, on one condition: we manage ourselves. We’d just have Ken Pitt as a managerial advisor – I didn’t want any official managers.

By then, my first daughter had been born, and we were living in Hendon, North London. I had to sort out my finances, talk to the bank, get everything back in order. That’s when I heard about Ray Rossi, Mick’s brother, who’d been managing the band behind the scenes. I wasn’t fully aware of what had been arranged, but I worked with him. Ray was sound – he’d helped launch our career.

‘You’re Ready Now’ is such a killer track – probably my favourite cover of any song, better than Frankie Valli’s original. What was the idea? Did it come from your skinhead days?

Yeah, these were the songs we’d hear in pubs. I’ve always loved Frankie Valli, and Ray and Mick did too. I loved it because we could mess around with it, give it a bit of nonsense. In rehearsal, Ray would provoke me, and I’d respond aggressively, so instead of a sweet voice, I sang it aggressively. That’s how the version came out – it was naturally us.

We originally wanted to record it for the Do It Dog Style album, but we already had too many covers – ‘Waiting for the Man’, ‘Quick Joey Small’, ‘Mystery Girls’ – so we put it aside. For the 1979 single, the plan was to put ‘Runaway’ on the A-side and ‘You’re Ready Now’ and ‘Situations’ on the B-side. In the end, ‘Situations’ was pulled and ‘You’re Ready Now’ ended up as the A-side.

Have you seen the clip on YouTube where someone put that track over footage of bootboys off to a Man United vs Leeds match in the ‘70s? It’s brilliant.

Yes mate, I was at that game! It’s a Leeds United fan who did it. A mate of mine sent it to me and said, “Wayne, remember, we were both there at the game.” I don’t know why someone put our track on it, but it’s great.

Yeah, it’s amazing. So, in 1980 you left the band again and moved to France, while they continued as ‘Slaughter’ with a more rock sound. But around the same time, the original band was rediscovered by the nascent Oi movement – Gary Bushell, Oi! The Album, ‘Where Have All The Bootboys Gone’. How did that come about? Did they contact you?

It was all scheming, money dealings, record companies, management. I didn’t give my authorisation for any of it. Some bands on those Oi compilations are ones I don’t want to be associated with.[1] To me, they don’t represent what bootboys were about. Some of these bands jumped on the bandwagon and used an image that doesn’t belong to them. Oi ain’t bootboy, and bootboy ain’t Oi. Bootboy is a mix of skin and glam – that’s what it is. If you listen to songs from Little Rooster, early Slaughter and the Dogs, or Slade – that’s bootboy to me. Foot-stomping music.

And then of course, it all became extreme right-wing…

Most of that came a bit later.

In ‘79, when I was in London, you could already sense it happening. Punk was losing its sense of direction. So the skins became the Ois, and the Ois became tools for the extreme right. That scared me. Kids – and I’ve always said this – shouldn’t have politics shoved at them through punk. I write about social stuff, everyday life, not politics. I don’t think any musician has the right to perform in front of young kids and give them an ideology, because they don’t have a politician’s degree. Most don’t know much about life yet, then they’ll hear the music and start supporting the ideology. Everybody should have the right to decide for themselves, not be indoctrinated.

But this way you’re just leaving politics to professional politicians. I think everybody has a right to express their views.

Yeah. But the problem is, the message always gets twisted. Any political point you make ends up coming back at you – turned around and smacking you in the face. I’ve even met people who think ‘Where Have All the Bootboys Gone’ is a nazi song. Once, when we played in Germany, some people started doing the sieg-heil salute during that song. I’m from the Jewish faith, so I stopped the show and recited Kaddish. Everyone was like, what the fuck? Then I told them straight: “You can’t go around doing nazi things. It’s stupid enough when people in England go ‘Heil Hitler’, and England was never even under nazi occupation. But in Germany, of all places – how irresponsible is that? You know exactly what happened in the past”.

Everyone is entitled to their opinions, but I wanted to make clear to them how stupid that behaviour is.

Wasn’t there some earlier incident at the Music Machine in Camden, probably in the late ’70s, where people were sieg-heiling at you?

Yes, I walked off stage! My aim, from the moment I started playing music, has always been simple: make people happy. Have a good time. Dance, laugh, drink, meet people. I’ve never had some big message beyond that. That’s part of why the London press didn’t like us – they were always looking for a “message”.

Why do you think the Oi crowd liked Slaughter & the Dogs, and did it surprise you?

Not really. Songs like ‘We Don’t Care’ and ‘Where Have All the Boot Boys Gone’ became anthems ‘cos they’re good for chanting. Then there was ‘You’re Ready Now’, which was a chanting song too. But they couldn’t put that one on their compilations because the copyright was too strong.

But in general, you didn’t like Oi music?

Some of it I liked for the energy, yeah. Other stuff I wouldn’t touch. These days I can’t really be bothered with it, but in the early years there was some that sounded alright.

There are young bands today I really like, though – Giuda, for example. They’re brilliant. Young, energetic, and focused on having a good time. No heavy messages, just entertaining people. And that’s what music’s about for me. The world’s sad enough without going to a gig to listen to someone preach politics.

You and Mick put out a strange comeback album as Slaughter and the Dogs in 1991, called Shocking. It had a kind of dance rock vibe, like Billy Idol or Iggy Pop’s Blah Blah Blah. How do you look back on it?

At the time I was just experimenting – samplers, machines, seeing where else I could go musically. I was learning, really. Noel, the drummer I’d been working with in France, came into the band because he was very disciplined. He didn’t shift his rhythm, so you had to work around the beat, not the other way round. I liked that.

But looking back, I think the result was a bit too serious.

You reformed again for the Holidays in the Sun festival in Blackpool in ‘96, and a few years later you did the Beware of… LP. It’s a strong album, which is a rare thing with bands that are around for so long.

Yeah. We wanted to go back to the roots of where we came from. So we moved to Manchester for a month, just to give the record that identity. For the first week, Mick and I would drive around at night, going past the places we used to hang out, looking at what had changed. Then we’d go back to the house and I’d write lyrics based on what I’d seen. The whole album was written in about two weeks.

Some of my mates who came along to the gig in Bologna hardly knew any Slaughter and the Dogs. Afterwards they said their favourite song was ‘Saturday Night’ – that was the one that really stood out to them. Which is remarkable, considering it’s one of your more recent tracks. Well, not that recent – you wrote it 25 years ago, haha.

It’s a very sing-along song. I remember filming the video in San Francisco. As we were walking around the streets shooting it, people were singing along with us. Beware of… is a good album – I like it myself. And that’s because of the way we went about making it. It’s much better than Vicious, which was too much of a guitar-hero album. There are a couple of songs on that one that are alright, but overall it wasn’t great.

You remember the gig you played at the 100 Club in London in 2017?

Of course I do. And do you know why? Because we never played it back in the day. We played everywhere else, the Greyhound, the Roundhouse, the Marquee, but never the 100 Club. That’s exactly why we suggested it to the owners.

It was a great gig, but far too many people. There was not enough space and that led to a situation, so I ended up watching the last third of your set with a bloody nose.

Oh no, I’m sorry that happened to you at our gig!

No no, these things happen – I had a great time. Fantastic show like every time I saw you. But then you fired the whole band August 2018, didn’t you?

What Mick did behind my back wasn’t good, and it wasn’t courageous. I’ve known him for 55 years, worked with him for decades, defended him constantly, never let anyone say a bad word about him. Our agreement goes back to the school playground in 1974 at Sharston, when I asked him if he wanted to be in my band.

Like any long relationship, there were good times and bad. But when my mother died, Mick never called me once. I gave him a month to reach out. When he didn’t, I severed ties. Over those 55 years I’d always been there for him. When his parents died, I was calling him twice a day, even though I knew he didn’t get on with his dad.

From the band’s point of view, the final straw was this. I had to cancel a great festival slot and ten dates in Germany because Mick told me no. He said he was working on a film script in Los Angeles. I was shocked, because these were well-paid gigs that could have really helped us financially. A few weeks later I found out, not from him, that he was playing in Japan with Walter Lure from the Heartbreakers, and he’d taken our bassist and drummer with him. That was it for me.

Unfortunately, Mick has always been all about money.

I’m sorry it all went that way! Your current tour is your last, titled ‘Time To Fuck Off’. Why is it time to fuck off?

Well, there’s a lot of people who’ve got kids, houses, cars, the lot, and they’re still trying to pass themselves off as punks. I think there’s a point where you’ve got to stop doing that. For me, the last straw was the Sex Pistols thing. Selling your soul to a multinational like Disney – I just couldn’t believe it.

I want to see young bands playing, and there’s plenty of them out there. I’ll carry on playing music, but not as Slaughter and the Dogs, and it’ll be different styles. You’ll see.

I remember three years ago you played in Bologna as Slaughter and the Dogs with a young backing band. A couple of years later I saw Claimed Choice, the bovver rock band from Lyon, and it struck me they were basically the same band…

Yes, yes. It was an experimental idea I tried to do. I brought young musicians in to show them off, giving them a little push. It backfired a bit, because they walked out and, on the strength of having played with me, got booked at Rebellion with their own band.…

In fairness, Claimed Choice are a very good band in their own right.

No doubt about that. Simone, the singer, is a skinhead, he believes in that way of life. I used him as a roadie at first. When I recorded Il tradimento silenzioso, I used session musicians I already knew. It was a bad period, but nobody could work, there were no gigs, nothing. So I got five guys into the studio and we recorded the album

When Covid ended and I started getting offers for shows, they couldn’t do it because they’d all gone back to their own bands and projects, which is fair enough. Simon said he had friends who could step in, so that’s what we did. They’re good lads.

We’re gonna have to wind up slowly but surely, Wayne. So let me ask you the last couple of questions. Looking back at your various phases – bootboy, glam, punk – which do you think had the best style?

I’m gonna tell you: the Wayne style.

What’s the Wayne style?

The Wayne style is all of them. I loved all of them. I take full responsibility for the glam, the skinhead thing, all of it, because that’s how I felt. People have different times, different phases, but I’ve always tried to be true to myself. I hope I have. I believe I have.

I still love football. Football and the skinhead thing – it just goes together. When I watch football, I get aggressive. It’s like driving a car – when you start driving, you lose yourself.

So when you watch football, you become a skinhead again. Nice one.

Yes, always. I support two teams: Manchester United, of course, and Lyon. I’m a big fan of Lyon, and I’m a member of the ultras there. Lyon and United have played each other three times in the last 12 years. Every time it happens, I don’t watch the game. Television off. No radio, no internet, nothing for two days. I don’t want to know. Because at heart, I know I’m a bigger United fan.

Last question. If you could speak to your 16-year-old self on your estate in Wythenshawe, what would you tell him?

Get a very heavy stone, tie a rope around it, tie the rope to your foot, and throw yourself into the river immediately (laughter)

Those are some nice closing words.

Seriously though, I’d tell him this: you’re going to experience one of the greatest privileges a human being can have, which is meeting all kinds of people. That’s what music gives you. The stage is my living room.

Well, I hope it will continue in some way.

It will continue. I’ve got two projects on the go, but I’m not talking about them yet.

Thanks for the interview, Wayne. And thanks as well for what you’ve given me personally. I’ve been listening to Slaughter and the Dogs since I was 15 – since the exact day I turned 15, actually – and your band has made my life a bit better.

[1] Years after Oi! The Album, Slaughter and the Dogs appeared on a great deal of Oi compilations. Among them, Pop Oi! (1989), Oi! Chartbusters (1989) 100% British Oi! (1997) Oi! The Singles Collection (1997), Lords of Oi! (1997), Addicted to Oi! (2002) Oi! Riot (2003) and Oi! Across the World (2004), among others.

What a brilliant interview!

Slaughter & The Dogs’ 2 tracks on the Roxy album were my faves on that record (I too was 15 at the time) and my ‘Where Have All The Bootboys Gone?’ 12″ single is one of my treasured vinyl records.

Looking forward to hearing Wayne’s new music.

LikeLiked by 1 person

One of the best posts so far!

I had never listened to “Beware Of” out of pure prejudice against reunion albums.

Thanks for mentioning it, I’m totally addicted to it now.

LikeLiked by 1 person