Following our recent article on the mysteries of rude boy fashion, we decided to dig a little deeper. While searching for material on rude boys in general, we found a 2006 piece that struck us as the best primer we’d come aross. Ironically, it wasn’t written in Britain – let alone Jamaica – but by a self-described ska fanatic from Italy, Sergio Rallo, for Skabadip.it. That site was a direct offshoot of Skabadip.com, the first Italian website devoted to ska and related genres, founded by Alessandro Melazzini.

A couple of notes before we begin. First, bear in mind that this piece appeared 23 years ago, and new information may have emerged since. Second, in Italian the term ‘rude’ is used much more freely than in English, referring to a broader attitude and scene rather than to rude boys in the strict sense. For example, Italian skinhead bars where reggae and Oi are played are known as ‘rude bars’ – the Sally Brown in Rome and the Bluebeat in Lecce being notable examples. Hence, towards the end of his article, the author applies the term ‘rude’ to all manner of things. What follows is our translation of Rallo’s piece:

Some time ago, a devoted reader of SkabadiP wrote to me asking about rude boys. He wanted to know what they were really like, what they thought, what their lifestyle was like and if they had a philosophy. As usual, I replied at length, within the limits of what I know. However, I also made the mistake of forwarding my email to Alessandro, the boss, who immediately seized the chance to order me to tidy up my reply so he could turn it into a nice little article for SkabadiP, that fine purveyor of ska culture – probably just to satisfy his own mischievous curiosity. After adding some more information following further research, here’s my article:

The story

Before I begin boring you to death, I should first make the obvious disclaimer: fortunately for me, I didn’t grow up in Kingston during the roaring ‘60s – even if, during my brief trip to the Green Island, I did encounter a tiny, crack-addled rude boy who threatened me with the infamous ‘ratchet’. So I can hardly claim to know exactly what rude boys thought or how they really lived. But from what I’ve seen, heard, or just picked up since becoming a ska fanatic (including from talking directly with the musicians themselves), I’ve formed a fairly clear idea of what they were like. I’m now going to set out what I’ve learned, starting with some historical facts in strictly non-chronological order.

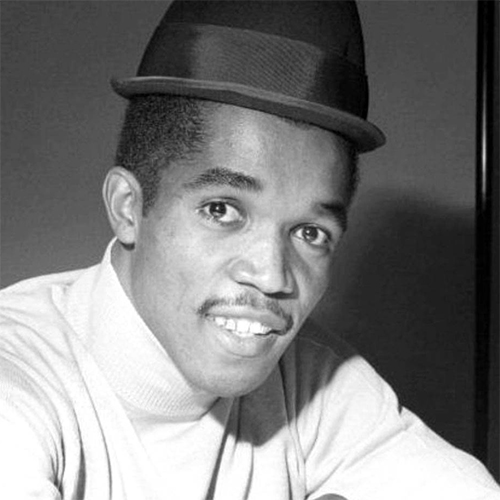

Prince Buster was almost certainly the first to mention rude boys in a ska track, with his excellent 1965 number ‘Rude Rude Rudee’. In the intro to this captivating instrumental, Buster declaims: “You say you are a rude boy / You also say you can’t go to jail / But you live in a glass house”, consequently warning: “So don’t throw stones”.

It’s worth noting that Prince Buster was reasonably qualified to sing about rude boys, having been the leader of a gang as a teenager, a semi-professional boxer, and for a few years the head of Coxsone Dodd’s ‘order stewards’ crew. Legend has it that during one of Coxsone’s sound system shows, Buster saved the arse of Dodd’s all-purpose assistant, talent scout, and DJ Rainford Hugh ‘Lee’ Perry, who was about to be stabbed by some random dance crasher trying to prove just how ‘rude’ he was – a fellow who, incidentally, was never heard of again after the incident.

If Buster’s track was the first to actually spell out the words ‘rude boy’ (the song’s tone, as can be inferred from the cited intro, is pedagogical), the attitude itself had already been in vogue for at least six years – unless I’m mistaken and the instrumental shuffle credited to Duke Reid’s group (Arkland Parks, Cluett Johnson, Rico Rodriguez, and Ernest Ranglin) called ‘The Rude Boy’ was actually recorded before 1959. This seems likely, given that Duke began recording in 1957 but only started releasing 45 rpm records once turntables had become widespread. Then again, I could be wrong, and the track may simply have been retitled when it was released on vinyl.

Either way, who better than the track’s producer, Mr Arthur ‘the Duke’ Reid – a former policeman who liked to strut around with a large gun tucked into his belt to strike fear into people – to give the first public recognition of these baddest of Kingston’s ghetto lads?

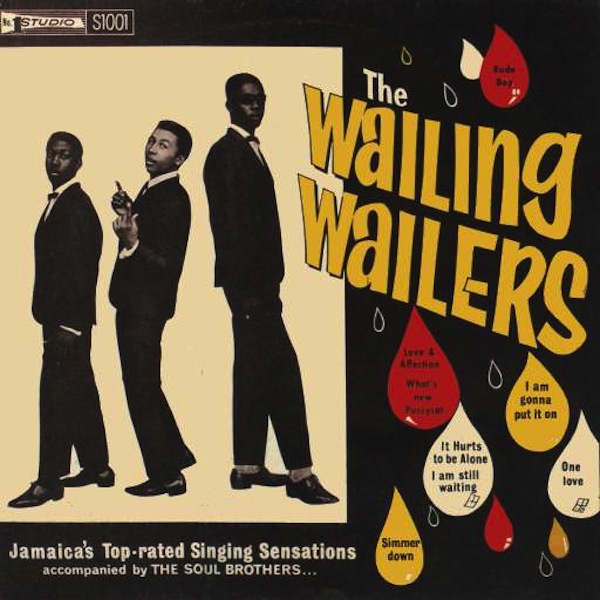

During the heyday of ska (1964–65), the rude boy phenomenon was also referred to as ‘hooligans’ – also the title of a song by the Wailers, a cult band among Kingston’s Trench Town rude boys; the Wailers had debuted barely a year earlier with ‘Simmer Down’, another rude boy favourite – or ‘dancehall crashers’ (see Alton Ellis & The Flames, Winston Jarrett). These terms all refer to the same thing.

Adding fuel to the fire, intentionally or otherwise, were the artists themselves. Notorious were the musical clashes between fans of Derrick Morgan and Prince Buster. When Morgan left Buster to work for Leslie Kong, Buster fired back with the scathing ‘Blackhead Chinaman’, to which Morgan responded with the legendary ‘Blazing Fire’. Such insults aimed at rivals were very common in the Jamaican musical tradition (see Lee Perry versus Prince Buster in ‘Prince in the Pack’, or a young Delroy Wilson unleashed against Buster by Coxsone in ‘Spit in the Sky’ and ‘Joe Liges’) – all intended as harmless fun and mockery. This is clearly evident in the fact that Perry wrote scathing tracks against his competitors, such as ‘Help the Weak’, while still taking part in their recording sessions for ‘Judge Dread’ and ‘Ghost Dance’…

In the case of Morgan and Buster, however, their respective rude boy fans took the singers’ mutual insults so seriously that they ended up brawling across Kingston’s dancehalls – knives at the ready! Jamaican politicians had to step in, forcing the two stars to shake hands publicly in an effort to convince their overexcited fans that, actually, there had never been any real animosity between them.

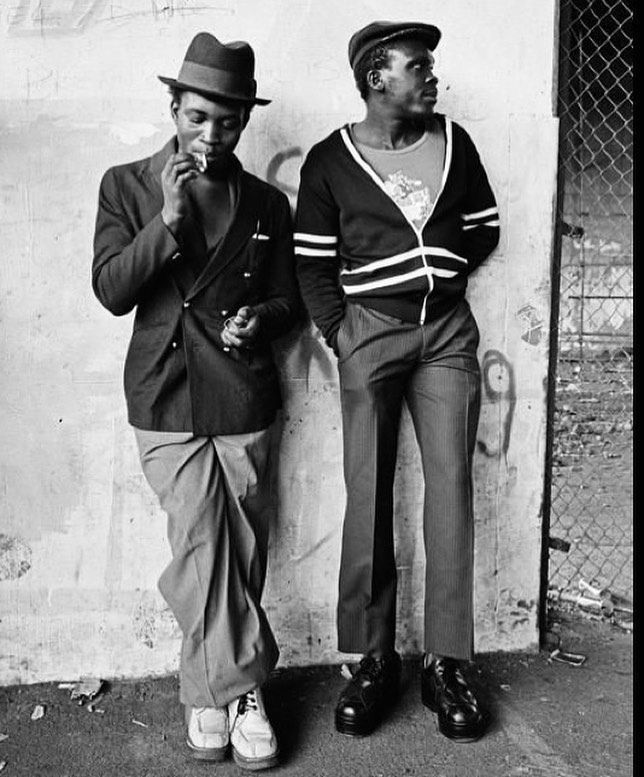

The most intense period of clashes is reflected in the music of 1966–67, by which time the term ‘rude boy’ had become widely recognised in Jamaica. In reality, the rude boys were simply thousands of young lads who were literally nobody’s children. They were as poor as only the Third World could be and looked up to robbers as role models, since these men made easy money and could afford the status symbols flaunted in the movies. To the rude boys, this seemed like a chance to ‘make it’ quickly and by any means necessary… after all, they had nothing to lose.

Some, without a doubt, were saved by the art of music, which, in hindsight, was a much less dangerous way of earning those same status symbols. Perhaps that’s why competition in Jamaican music was always particularly fierce. Between 1966 and 1967, countless tracks were dedicated to what are now universally recognised as rude boys, as summarised by Trojan’s legendary 1993 compilation Rudies All Round, subtitled Rude Boys Records 1966/1967, and the earlier 1992 collection Tougher Than Tough. These lads caused such havoc in the Caribbean city that the government had to send soldiers to patrol the streets and support a police force already notorious for its brutality – for reference, listen to ‘Copasetic’ by The Rulers or ‘Gunmen Coming to Town’ by the Heptones. In Jamaica, punishments for all sorts of crimes included flogging, and there were no plea bargains.

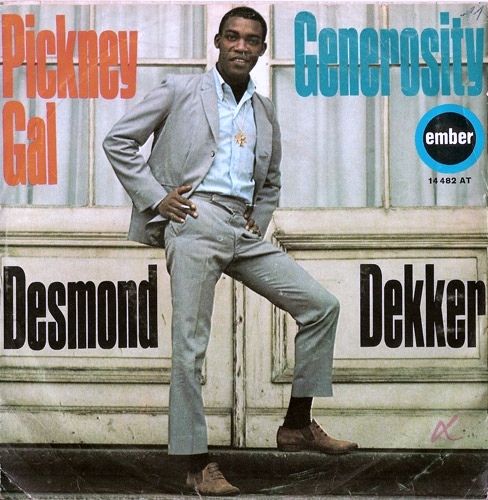

It was around this period that some of Jamaica’s most captivating ska and rocksteady tracks were recorded: Prince Buster’s ‘Too Hot’ (like the aforementioned ‘Judge Dread’, where Buster, playing the fearsome Judge, condemns rude boy Emmanuel Zacharias ‘Zackie’ Pom – that is, Lee Perry – to 400 years in prison), Desmond Dekker’s ‘Rude Boy Train’ and ‘Rudy Got Soul’, the Valentines’ ‘Blam Blam Fever’, the Clarendonians’ ‘Rudie Bam Bam’, Joe White’s ‘Rudies All Round’, and many more. As you can infer from the titles, many tracks celebrated the rude boys, some condemned their bad behaviour, and others yet tried to lead them onto the right path – the most famous example of the latter being Dandy Livingstone’s ‘Rudy, A Message to You’.

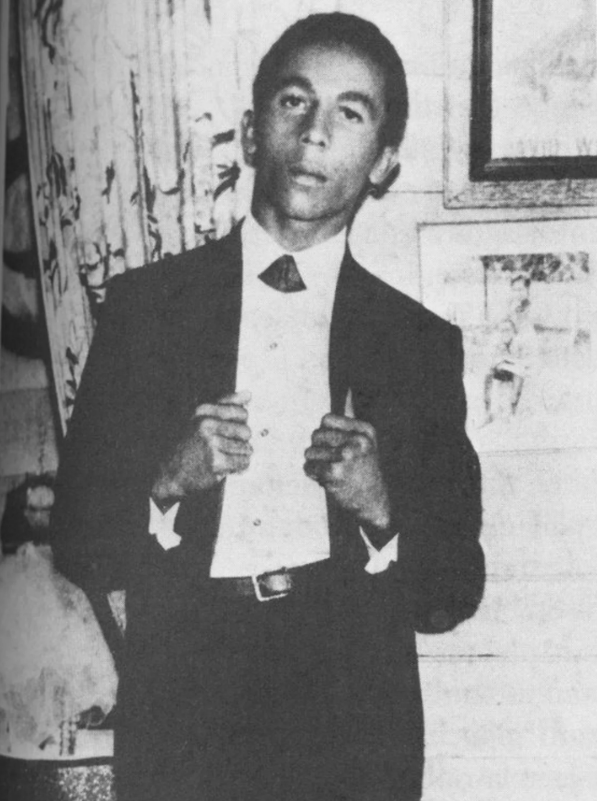

Some songs indirectly referenced the exploits of a real-life rude boy: Vincent ‘Ivanhoe’ Martin, nicknamed Rhyging, whose life is described in detail by Chris Prete on the back cover of Tougher Than Tough (Trojan, 1992), an album dedicated to rude boy ska, rocksteady, and reggae.

Vincent Martin was tiny, vicious, and had an innate hatred of the law. Maybe you can’t really blame him – by the age of fourteen, he had run away from his country home, sneaking into a lorry bound for Kingston, and the law had never given him a chance to earn a living legally.

From petty criminal, Vincent Martin rose to legend through a series of victorious standoffs with the police over robberies, earning the admiration of Kingston 11’s rough neighbourhoods. That same community later shielded him fiercely after a dramatic prison escape. Regarded as a hero by the notorious local underclass, he met a spectacular, movie-worthy end: gunned down by police on Lime Clay Beach after killing three officers and wounding two others.

His story is vividly retold in the cult film The Harder They Come (Perry Hanzel, 1971), worth watching not least for its fantastic soundtrack, with an unexpectedly mature and talented Jimmy Cliff playing the legendary rude boy. The film is highly recommended for anyone wanting to explore the subject and is widely available on DVD – so, if you’re short on Christmas gift ideas…

The film doesn’t offer any indulgent sociological excuses (you know, things like “it’s society’s fault”). The main character doesn’t become a rude boy because he is forced to. He simply, and foolishly, makes a series of wrong choices that lead him there. His reasons are fairly trivial: to attain certain status symbols and to emulate the swagger of tough guys in Westerns (those by Sergio Leone or starring Franco Nero were especially popular), gangster flicks (“Al Capone guns don’t argue!”), or spy movies (007). In Perry’s reconstruction, this is emphasised by the fact that ‘Ivanhoe Martin’, played by Jimmy Cliff, is also an excellent singer and songwriter – a talent Rhyging himself may have lacked.

With the shift from ska to rocksteady, Jamaica’s social ills seemed to explode alongside disillusionment with the over-hyped prosperity promised by politicians. Four years after independence, that prosperity was nowhere to be seen in the harsh realities of everyday life. People were migrating from the countryside to an ever-expanding Kingston (as the film depicts), and it’s no coincidence that The Ethiopians rose to fame in mid-1968 with ‘Everything Crash’, a song that beautifully captures a situation that was only getting worse:

What gone bad a morning can’t come good a evening woy, every day carry a bucket to the well, one day the bucket bottom mus’drop out, everything crash.

Don’t you watch my size

I’m dangerous

Between summer 1967 and spring 1968, the situation was such that Prime Minister Shearer’s police had killed 31 people in various circumstances – some by accident, others as a result of gratuitous brutality. Even the police, at the heart of the controversy, went on strike to protest about the low wages they were paid, one of the main causes of their rampant corruption. Everything was well and truly falling apart.

A final note: even today, Jamaica ranks second only to Colombia for deaths in shootouts between ‘gunmen’. As of today, the toll has already exceeded forty, mostly in and around Kingston, and the year is far from over. [1]

The term ‘rude boy’ and themes around young people clashing with each other or with the police in the slums, remain popular in Jamaica. The rhythms may have changed, but the issues persist. In the ’90s, I swear I saw digital ragga records with titles or artist names like Ruud Buoy Staylee, or something similar, on the reggae shelves. As I’ve only sporadically listened to that music, I take this opportunity to ask anyone with info to share it – I’d be grateful.

2 Tone

Towards the end of the 1970s, talk of ‘rude boys’ resurfaced with the movement inspired by the 2 Tone label, founded by Jerry Dammers. Between 1979 and 1981, skinheads who embraced the ‘dirty and tough’ vibe were considered ‘rude’ and saw themselves as direct descendants, given that reggae had been in their DNA since at least 1968. Many ska fans who weren’t mods or skins but loved the music of The Specials, Madness, The Beat, and similar bands also adopted the accompanying sharp look of sunglasses and beat-style clothing. At least in the media, they were all regarded as ‘rude boys’.

Of course, the mods were also ‘rude’, having been captivated by ska before the skins got into reggae. For them, ‘rude’ behaviour also included the reckless use of amphetamines. The differences between these groups were often subtle, especially to the media, which tended to lump everything together at the time.

Mostly, however, the term ‘rude boys’ came to identify the followers of the new ska movement:

“Alongside The Specials and The Selecter, Madness are the creators of the most exciting and important musical development in England since punk rock: they are so-called ‘rude boys’, that is, ‘tough guys’. There’s no doubt this is a real movement: it encompasses racial, social, and musical factors. Racially, it is founded on black and white. The band line-ups feature both black and white members (except in the case of Madness), and their clothing colours reflect that. Socially, all members (including The Beat, The Bodysnatchers – apparently all-female! – and Dexy’s Midnight Runners) come from London’s underclass: the whites are mostly ex-punks or ex-skinheads, the blacks are Jamaican immigrants, hence the nickname ‘rude boys’”.

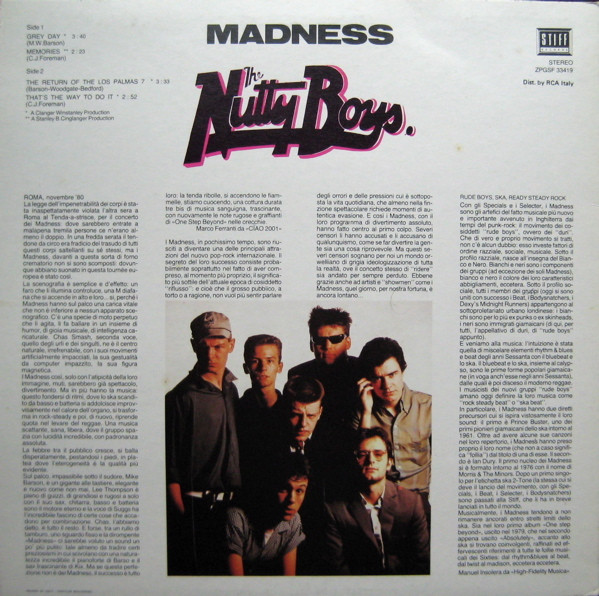

In this 1981 article, reprinted on the back of Madness’s The Nutty Boys EP (Stiff/RCA Italy),[2] journalist Manuel Insolera may have been unsure whether the Bodysnatchers were an all-female band, or unaware of the Jamaican rude boy tradition in its entirety, but his writing captures the ‘80s atmosphere, which was dominated by youth tribes, each instantly recognisable by their distinctive appearance. Today, with the tribes largely gone, there are still people passionate for ska and its derivatives, although the sharp look of three-button jackets, skinny ties, Dr Martens boots, Crombie coats, braces and pork pie hats – undoubtedly one of the best styles ever – is followed less rigidly.

Following this brief historical sketch, I can move on to the second part of this article, which concerns the philosophy and/or lifestyle of a true rude boy.

The philosophy

I don’t think a ‘rude boy philosophy’ ever existed. If it did, it was hardly any different to the philosophy of violent youth gangs in the US or Jamaica today, who are happily trafficking in drugs and weapons, contributing to the high death tolls I mentioned earlier.

For many skinheads, being ‘rude’ simply means being yourself – or, more precisely, once you’ve left school: work, beer, Oi music to pogo to, ska music, and – here lies the real test of who’s ‘rude’ and who isn’t – knowing how to skank to it properly. Then there’s football on Sundays,[3] your woman (who doesn’t need to be a skin); no politics; and mates with a capital M. In essence, for some skinheads, being ‘rude’ is just a kind of healthy normality, even if the odd scrap occurs due to certain temperaments.

Personally, I think the figure of the rude boy in the strict sense – that is, in the original Jamaican sense – has fascinated Europeans far more than it probably deserved. Those discovering ska and reggae – and subsequently Jamaican cultural traditions – were drawn in by his style, swagger, and rhythm.

British bands, especially The Specials, helped revive the myth, covering songs like ‘Rudy, A Message to You’, ‘Too Hot’, or ‘Rude Boys Out of Jail’, alongside their own originals in a similar vein, like ‘Concrete Jungle’. In doing so, they fired the imagination of countless listeners who identified with a certain image of the rude boy: smartly dressed and tough enough to command respect, but above all, in love with an irresistible rhythm.

[1] As of 2024-25, the murder rate in Jamaica has dropped significantly: in 2024 there were around 1,141 homicides, down from about 1,393 in 2023, and for part of 2025 the trend continues downward, though gun violence and gang-related deaths remain a serious problem – Editor

[2] The Nutty Boys was an expanded, Italy-only 12’’ version of Madness’s 1981 single Grey Day, and Insolera’s article printed on the back cover was taken from the Italian High-Fidelity Musica magazine – Editor

[3] Football matches in Italy take place on Sundays rather than Saturdays – Editor