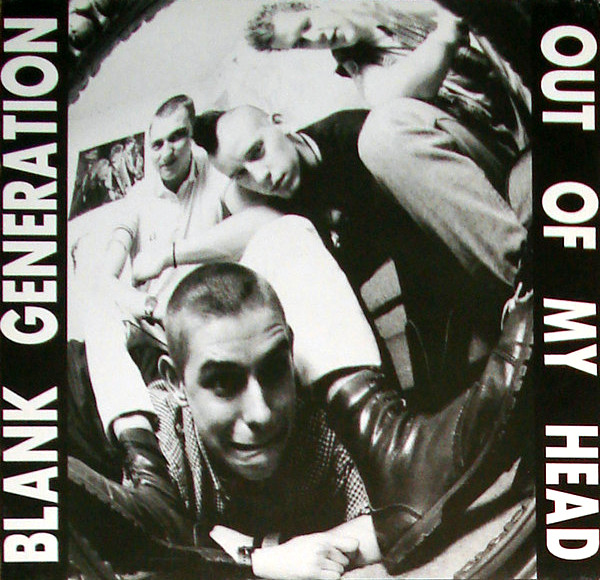

Though not often brought up today, there was something of an Oi revival happening in the early 90s. In England, some of the foremost acts were Boisterous, Another Man’s Poison, Braindance and Argy Bargy, and the must-have compilations of the hour were Oi! The New Breed and British Oi! – Working Class Anthems. The latter album also comprised a band of youngsters from High Wycombe, a market town some 30 miles west of central London. Named Blank Generation – though not after the Richard Hell song, as we shall see – the group managed to record a demo, a single and the album Out Of My Head during its four-year existence.

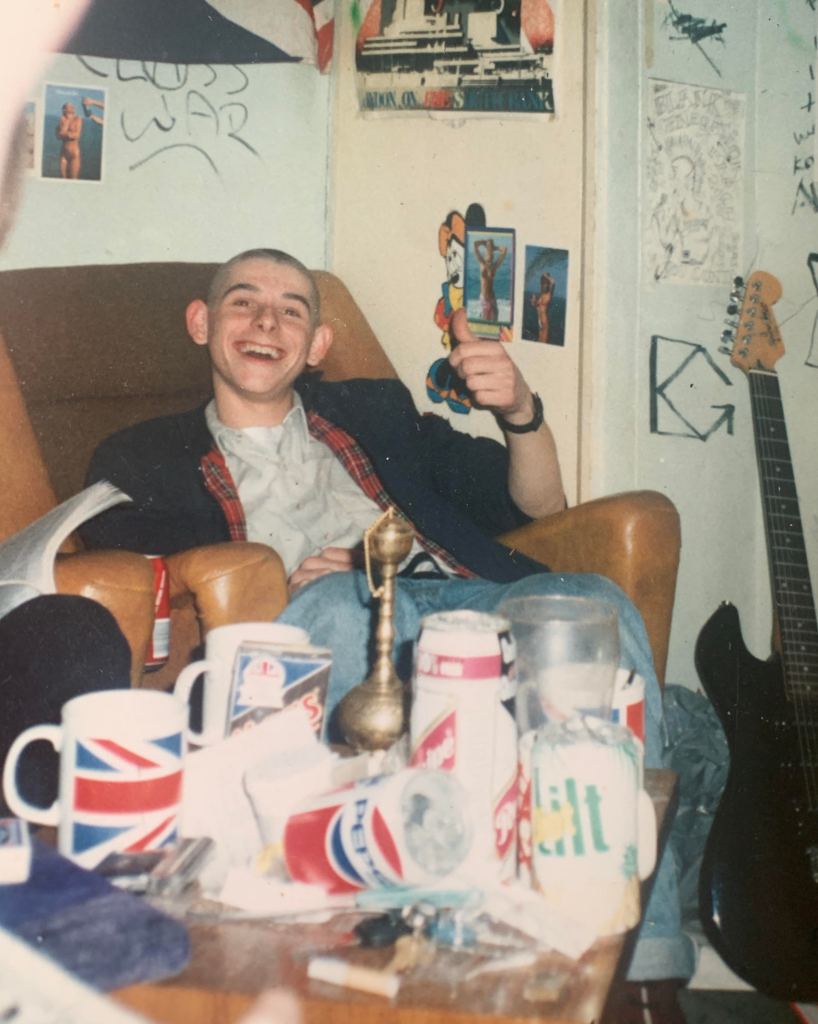

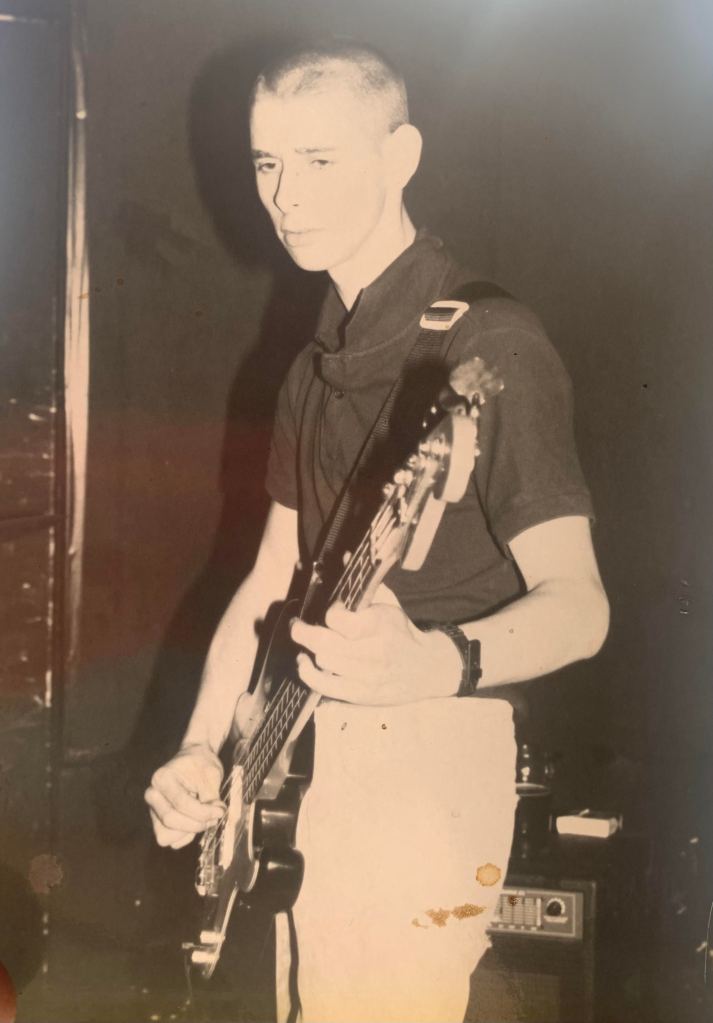

The core of the band were the industrious brothers Benny and Chez on vocals and bass respectively (alongside Kneill on guitar and soon joined by Don on drums). Today they’re both based in London, and if you live north of the river you’re likely to bump particularly into Benny – for, no matter how much he insists that he’s through with the skinhead world, he’s magnetically drawn back to it time and again. Recently it struck me that the story of Blank Generation has never been told, but probably should be, as it offers a glimpse of the British Oi scene at a particular moment in time. So I decided it was time for a historical interview with Benny and Chez.

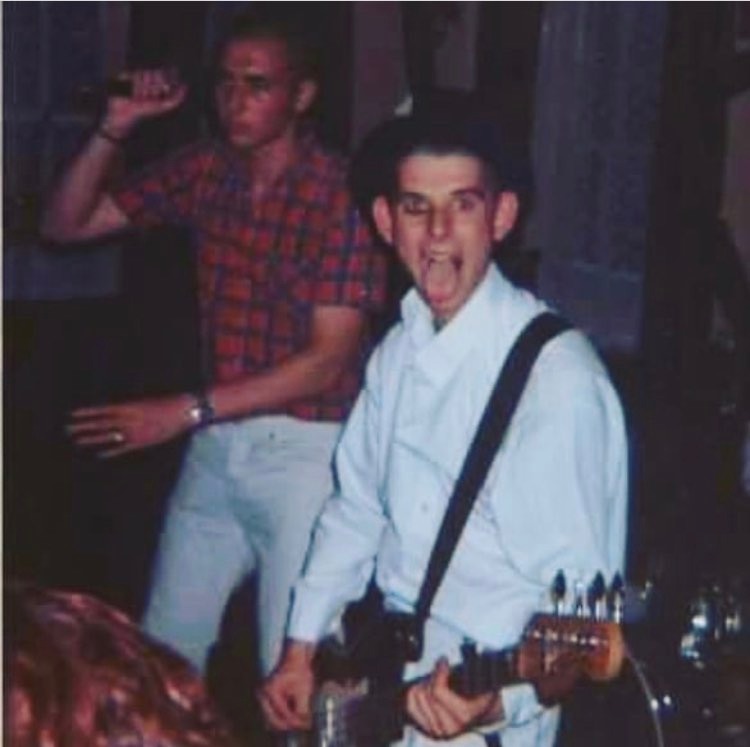

Matt Crombieboy

What was it like growing up together before you got into punk?

Benny: We grew up in a house surrounded by rock ‘n’ roll music. Our dad was a rhythm & blues guitarist, so we had a very early exposure to live music. I met Kneill, who would become the guitarist in Blank Generation, through his cousin, who I was friends with at school. Our dad taught Kneill to play and said he was the most natural guitarist he’d ever seen, with the speed at which he picked it up.

When we first met Kneill in the 80s we were all into hip hop. Kneill was an incredible breakdancer. Then, I can’t remember how or why, we got into rockabilly – that’s when we first got the idea to be in a band. Nothing ever happened, but the seed was planted. Not long after that we got hold of a VHS copy of The Great Rock N Roll Swindle and watched it and watched it until we were punks.

Your hometown of Wycombe is an ‘overspill town’ outside London with a long-standing punk and skinhead tradition. I’m thinking Xtraverts, Gavin Watson and of course the most-photographed skinhead of all time, Symond Lawes. But you lot are a bit younger.

Chez: I had, and still have, a lot of respect for a lot those lads Gav, Symond (Scab), Barry, John, Lorp, Biff, few of the others too. They looked out for us. Gave us the guts to go and do a lot mad things, I reckon. Always will have time for ’em.

Benny: And good that you Mention The Xtraverts. Our dad was the manager of The Xtraverts in 1977 and their first single Blank Generation was released on Spike Records. Spike was our dad’s name. We took our name from the song to continue the legacy.

Oh wow, I had no idea. So what made your rhythm & blues guitarist dad want to manage a punk band?

Chez: When our mum and dad got married, their best man was a gentleman called Ron Watts, an old Wycombe legend who used to run the Blues Loft at the Nags Head, High Wycombe – this venue will come up later, I’m sure. Ron was also the promoter of the 100 Club in London and in September ’76 he put on the punk festival with the Pistols, Clash, Damned and Buzzcocks there. His book 100 Watts of Music is a great read, by the way.

Our old man was a gigging musician. Him and his pal Wid bought a PA and started putting on bands at locals venues. Ron brought all those punk bands to Wycombe, helping to create a scene there, and our old man was hanging out with Ron and put on a few acts along the way, e.g. The Lurkers – and as the Xtraverts were local, it all came together. He also played bass in a cracking punk band called The Legendary Flobs, who recorded some unbelievable songs – look ‘em up if you can find ‘em.

Also, our mum was in a punk band called Pink Parts in ’76-’77. Later, she went on to be a part of the riot grrrl punk scene and was playing in a punk band at the same time we were in Blank Generation. She used to wear a t-shirt of our mates’ punk band The Gasmasks t-shirt.

As a riot grrrl, did she never complain to you that Oi was too macho?

Chez: She said a lot of things about it, and a lot of what she said ended up being true – like its darker political edges and those that hang onto it with bad intentions. But she knows the difference and understands the world. She used to take me to West Ham games at Upton Park throughout the 80s. We were right in the mix. You couldn’t get a more macho environment than that. She bought me some Business records too I remember.

Benny: She bought me my first real MA-1 flight jacket for my 21st birthday.

Was Wycombe a ‘tough’ town, then?

Benny: Olden-days Wycombe was a very tough place, with lots of drinking and fighting and a few race riots in the heat of summer. But it all died down a lot when ecstasy arrived in town in the late 80s. It became a massive drugs town for ages – everybody was high because decent speed was cheap and readily available.

Chez: Wycombe was a tough place in the 80s. Just things like every London football firm had numbers that travelled up from Wycombe. It had a big, confident Caribbean and Pakistani community that didn’t take any shit. It was divided by class, surrounded by some of the richest parts of the world, I think. But full of poor working-class black, white and Asian people.

Was there still loads of skins and punks around when you were growing up?

Chez: There was loads of punks and skins about the area when we were kids. The playgrounds were littered with empty glue bags, that’s my main memory of ‘em then. We also had Xtraverts round our house a lot in the late 70s.

Benny: By the time we were punks all the older punks and skins in Wycombe had moved on to rave. They used to call us The 10 O’ Clock Shop Mob because we used to hang out by the village shop. Despite having moved on to rave they still had an Oi band called The Hoopers, who were a massive influence on us, and not just musically. They taught us some very important life lessons – some good, some not so good, but all important. Before we had met them, we knew of them through rumours of their gigs turning into bloodbaths of violence, which wasn’t true. As usual, perpetuated by people who had never actually been. One day we were hanging out at a friend’s house and there was a knock – it was Johnny Hooper, lead singer of The Hoopers. He said, “You lot the 10 O’ Clock Shop Mob? I heard you got a band, wanna support The Hoopers next week?” We said, “Erm, alright then”.

After all I said earlier, that gig did end up in a punch up!

Chez: Yeh, I was going to say… I’m pretty sure every gig we did with them or saw ‘em play ended up in some kind of aggro. Anyway, me and Kniell became best pals, but Benny and him started Blank Generation. So, given that my brother and best pal had started a band and said they needed a bass player, not wanting to miss out I told them I could play bass. They accepted this piece of bullshit with little questioning, even though they both knew me pretty well. I gave ‘em a recently learned rendition of ‘Belsen Was A Gas’ on two strings of an acoustic guitar and I was in. We did our first gig two weeks later at the Morning Star, High Wycombe. We also nicked a couple of lads off a local band called The Taxmen, but only Don the drummer stuck it out.

What year are we talking?

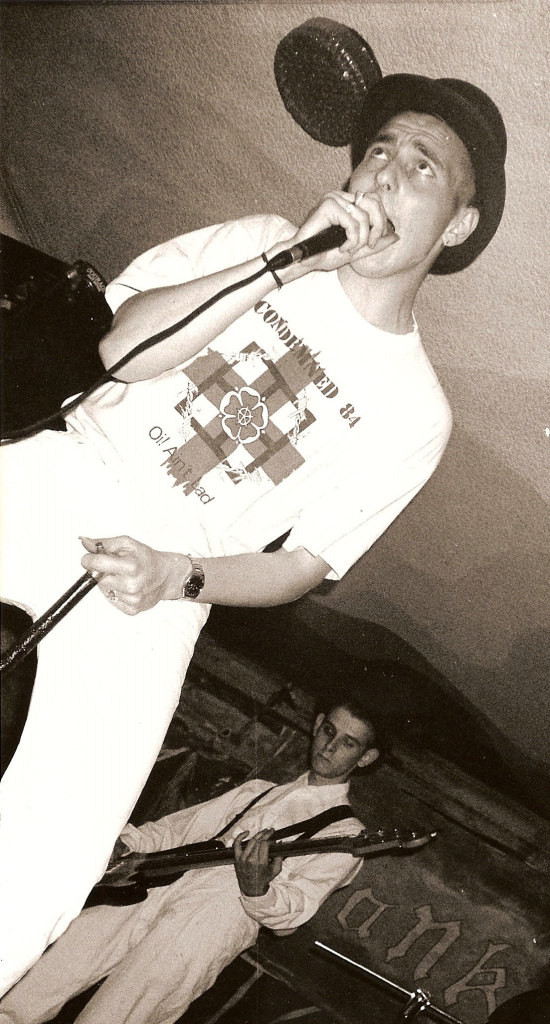

Benny: Our first gig was May 18th 1990. I still have a little celebration to myself on my anniversary of being an entertainer, in the loosest possible sense.

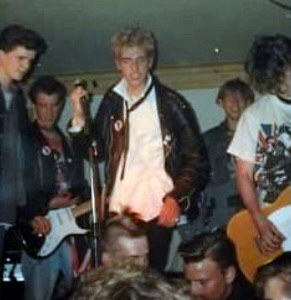

Can you tell us about your strange teenage obsession with Billy Idol, Benny?

Benny: At the first gig with The Hoopers I had blonde spiky hair and a leather jacket. An old Wycombe punk called Batman came up to me and said “You think you’re Billy Idol, you’re not”. It became a running joke whenever Billy Idol is mentioned, even to this day.

So were you well-connected with London at the time, or was Wycombe more or less self-contained?

Benny: At the time there were lots of gigs of the original punk bands playing together. Great gigs. You would see Sham, UK Subs, Chelsea, Vibrators, 999 and some of the lesser known originals like The Blood. All-day gigs at Brixton Academy and The Astoria – we would always come to London for them.

London was a very different place then, no? In 1990 even Carnaby Street wasn’t so bad yet – still had all the different subcultures hanging out there on the weekends, or so I’m told.

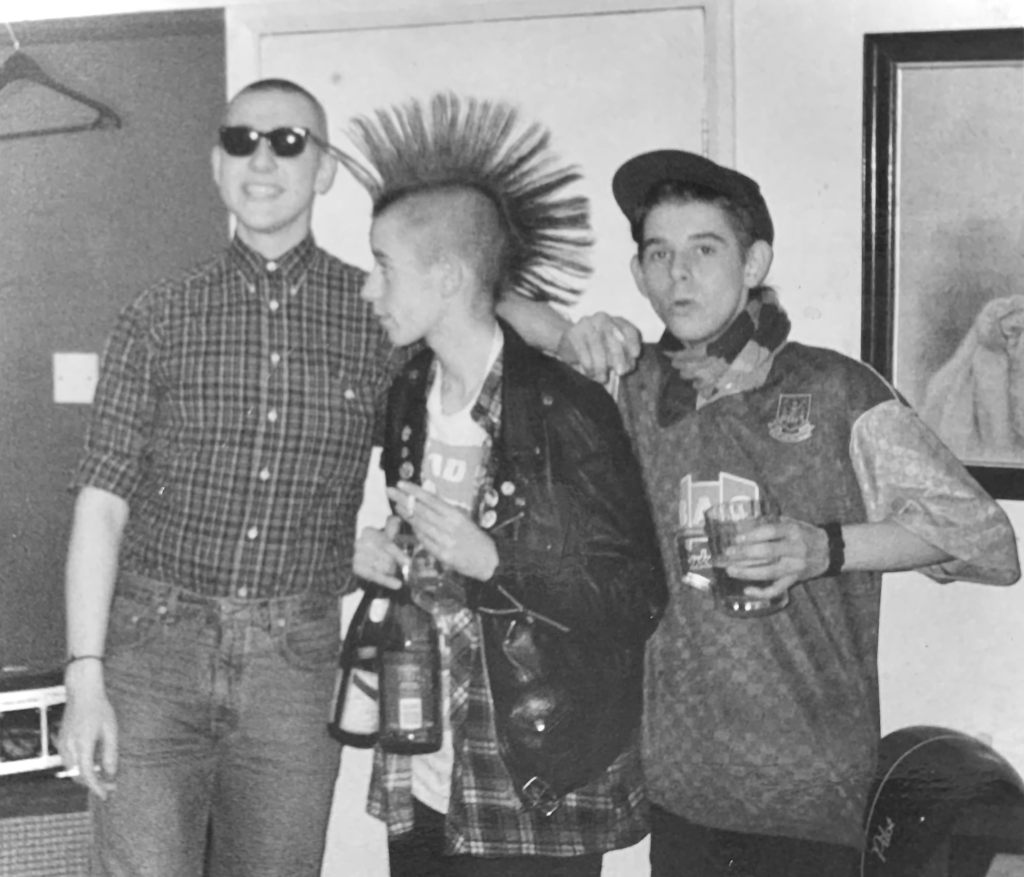

Benny: Yeah, we used to do our clothes shopping in the Merc shop when it sold proper gear, before Ben Sherman went Liam Gallagher – back when they used to make uncomfortable shirts. There was no internet then and clothes in Wycombe were shite, so if you wanted something you had to go to London.

Chez: The early 90s were a different age. There were loads of different types of shops in Carnaby Street. There was a hip-hop shop, a few skinhead shops, and loads of goth and punk stuff. Benny would enjoy buying trousers he would never wear from there. As many hole Doc Martens as you needed.

What were some of the trousers you’d never wear, Benny?

Benny: I bought a pair of dogtooth sta-press that would give you a headache to look at.

Hah, I had a pair of those too. Wore them once, sold them on.

Benny: Mine were hanging on my cupboard door for ages, and when I went to move them, I saw Kneill had glued them to the door.

Chez: Yeah, me and Kniell were just punk herberts. Benny was smart and had a bit of class. Went after things that didn’t always work.

(laughter)

Apart from Carnaby Street, what were the skinhead hangouts in London at the time?

Benny: We didn’t really hang out much in London back then, only to go clothes shopping or for gigs. The Stick of Rock in Bethnal Green was a good place – they had lots of punk and Oi gigs there.

And in Wycombe?

Benny: Our pub was The Flint right outside the train station. It was Wycombe’s alternative pub at the time – a mix of punks, skins, bikers, indie kids and ravers used to drink in there. They had live music most Fridays. Not much in the way of punk though, but it was a lively pub. Other Wycombe pubs of the time were The Roundabout and The White Horse, which both had live music.

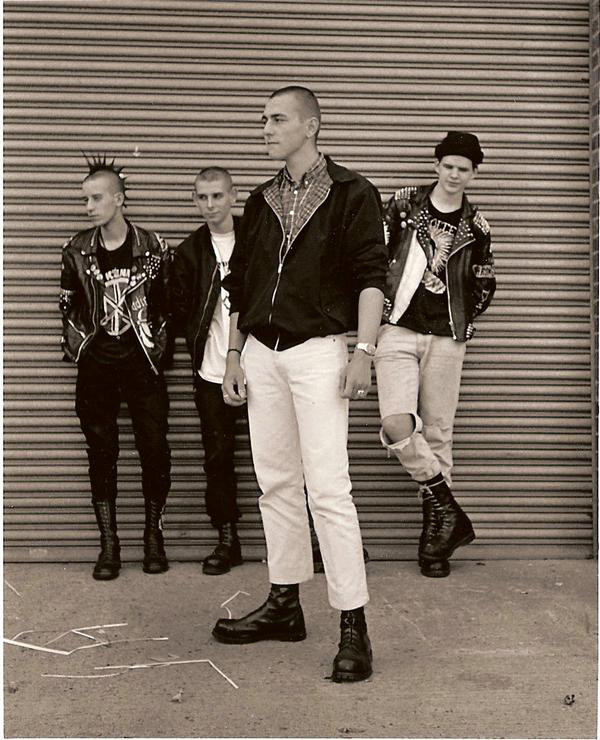

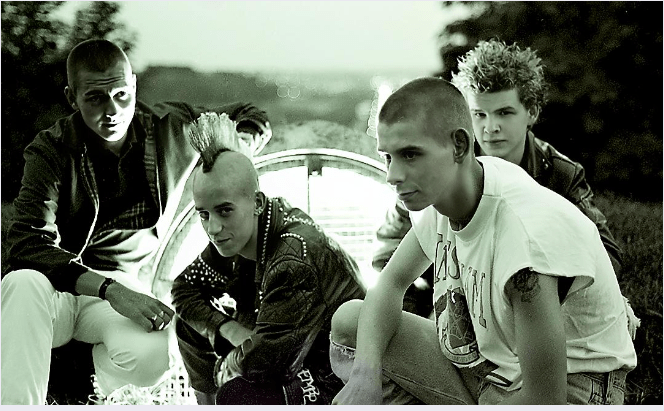

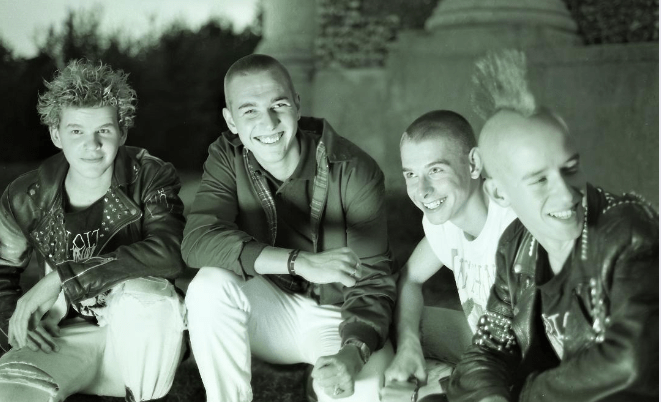

So what were relations between skins and punks in Wycombe and in London around 1990? Looking at your old pictures one gets the impression it was all the same scene. In countries like Germany, Poland and France at the time, punks and skins weren’t friends, to put it mildly. One might even call it total war.

Benny: It wasn’t really like that here. Punks and skins used to all go to the same gigs. If there was trouble it was always skinheads, though.

Chez: Yeah, the skins didn’t really care who they had trouble with, to be honest.

On the continent it started changing around ’93, when there was a bit of an Oi revival underway. But in the years from say, 1984 to 1992, most skins and most punks were enemies.

Benny: I think we saw things differently because we were heavily influenced by the UK 82 punk movement, where punks and skins were much more integrated.

Chez: Plus, there wasn’t a lot of skins by the time we came around. We weren’t seeing packed venues. Small groups of dedicated people mostly.

Benny: In Wycombe, there was a place called Roundabout where the anarcho-punks used to drink. There was a kind of rivalry between us for a long time. One night I was in there and the drummer of Wycombe punk band Cidefex came over to me and said “I know there has been some bad feeling between all us guys, so we chipped in and bought you this” and handed me a loveheart sweet – it said “skinhead” on it. I was really moved. We all became great friends after that and realised we weren’t all that different at all. We organised a punks vs skins football match one Easter, which became a regular thing but developed into punks vs drunks when we teamed up to play a team of the regulars from the Hobgoblin pub. This was much after Blank Generation, but the rivalry had started during that time.

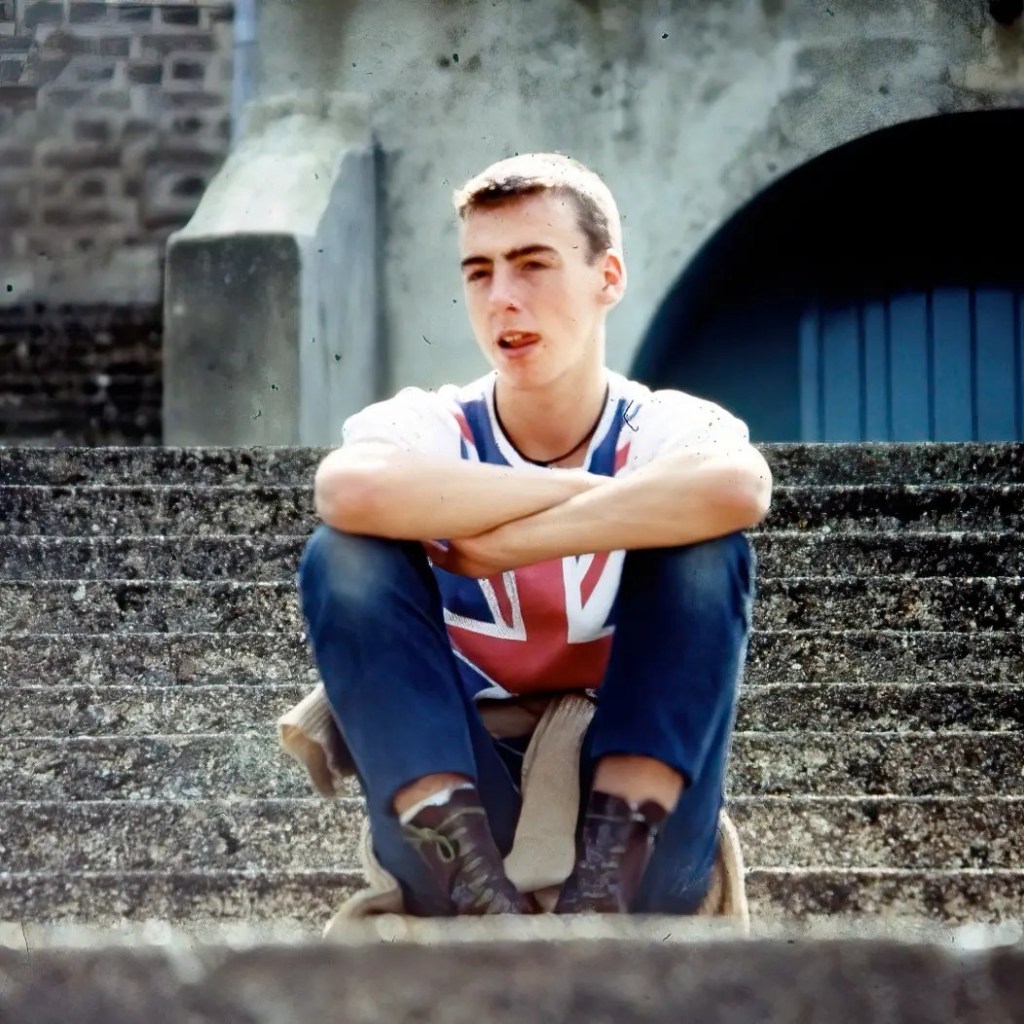

So when you went from punk to skin yourselves it wasn’t really such a big step – more like changing your hair colour?

Benny: Yeah, for me it was the Hoopers influence, that introduction to Oi – I just ran with it as soon as that door was opened.

Chez: I was a punk in skinhead clothing. The real skins, like my good friend Lee from Wycombe, would love to rib me about tucking my combats into my boots. I was a shit skinhead really, but I loved Oi.

I vaguely remember The Hoopers from an Oi compilation. Didn’t they have a song called ‘I Don’t Scare’?

Benny: That was the Kicker Boys, but on the same compilation, Pop Oi. The Hoopers song was ‘Ginger Cringe’.

Ah yeah, that’s right.

Benny: Darryl Smith of Cock Sparrer was in The Hoopers back then. He was 17.

Chez: His career went downhill when he left The Hoopers (laughter). They had some great songs. ‘Slobs Not Jobs’.

Benny: Then they weren’t really a functioning band but would occasionally do a gig. The last gig they did was in ‘93 at The Stick Of Rock in Bethnal Green, East London with us and The Blood. That was an amazing night.

From when till when were they around, roughly?

Benny: I think they started in ’86, so maybe ’86-’93.

Chez: Darryl also helped produce the Blank Generation album.

THE DEMO

Let’s talk about your demo first. It has two songs. One is called ‘Last of the Bootboys’ and the other one, almost inevitably, ‘Skinhead’. I like these recordings very much, but I seem to remember Benny saying he doesn’t?

Chez: ‘Last of the Boot Boys’ was great in my opinion. Not so sure about ‘Skinhead’…

Benny: I thought they were great at the time. Kneill had just learned to play lead properly. You soon learn though that real Oi bands don’t shout “skinhead, skinhead” – that’s wally shit.

Condemned 84 sure did. A lot.

Chez: There was a lot of muggy shit about. Maybe we’re a bit harsh on ourselves, but there’s so much class in the scene. You don’t want to single yourself out as a mug.

To be honest, when we recorded the demo, which I think was in ’92, we were still really shit – that has to be understood. Basically, there was Blank Generation before our gig with Guitar Gangsters and Blank Generation after. We were so shit at that gig, we decided not to be shit anymore.

Benny: Yeah, nightmare gig. Feeble doesn’t come into it.

The demo may not be the height of originality, but I think it has its charm. What did you do with it, send it to zines and such?

Benny: We sent it to Hammer Records. They’d heard of us because we used to support Darryl Smith’s band The Elite and someone had mentioned us to them. They asked for a tape and we sent that.

Chez: Didn’t they get us the funding for the British Oi! – Working Class Anthems compilation?

Benny: Yeah. In the meantime, between sending it and getting asked to record something for Working Class Anthems, we had gotten much better at song writing.

Who was doing Hammer Records?

Pat Townsend of Straw Dogs.

By then, there was a bit of an Oi revival in England too, wasn’t there? Bands like Boisterous, Another Man’s Poison, Argy Bargy…

Benny: Yeah, it was a very lively time. It was like there was all these little time-warp towns all over the country with little pockets of punks and skins. They usually had a band too. In those days there was no internet, so communication was phone calls and writing letters, but a nationwide scene was built like that, through devotion to the cause.

Condemned 84, Pressure 28 and Section 5 were on that Working Class Anthems compilation too. Did you get to play with them?

Benny: We played with Pressure 28 a few times and a couple of times with Boisterous. I think we played with Section 5 once too.

No Condemned 84?

Benny: No. I think I would have liked to, back then I was quite a fan. I loved their tracks on Working Class Anthems.

Yeah, they must have been pretty good at the time. There’s a live 1988 video on YouTube, and they’re an incredibly tight live act there, really attuned to each other. Too bad they also seem to be playing Italian Hammerskin parties and such.

Benny: I know. I doubt I would go to one of their gigs nowadays. I’m too far removed from it now.

Chez: I don’t know them personally, only through a few letters we exchanged in the post-Working Class Anthems, pre-email period. I don’t know what their politics deep down are, but as a band I thought they were alright.

THE SINGLE

Moving on to your single, ‘Another Victim’, it really has more of an English Dogs, almost G.B.H rather than Oi sound, with quite heavy guitars and a fair bit of distortion. Were you technically still an Oi/skin band at the time, or were you trying to move on?

Benny: The music was heavily inspired by ‘Psycho Killer’ by English Dogs. By that time the music we were listening to was a lot harder, The Exploited had moved into a more hardcore sound and we loved it and wanted a bit of that. The B side, ‘No Consolation’, is still my fave Blank Generation song.

Chez: From a recording, sound point of view was probably where we wanted to be. Hard, fast, energy, loud, well-played and well-produced. I wish some of our later stuff had been that well produced, that’s for sure.

The lyrics of ‘Another Victim’ more or less run along the lines of ‘Rapist’ by Combat 84. You aren’t calling for a stronger government, but you do seem to be calling for capital punishment: “We’re gonna fetch the rope”. What made you feel so strongly about the subject of child murder at the time?

Benny: ‘Another Victim’, that one is a story in itself. Hammer wanted us to cover a song by Peter and the Wolf for our first single, but we didn’t want to do a cover. Chez wrote the song after reading about the Sean Williams murder. The subject matter is something that has never sat very well with me and Chez, but it all happened so fast we didn’t really think it through. Most of the Oi bands at that time had a song about similar subjects, but our one was about a specific case. We didn’t think of the effects it could have, what the family would think and so on. Looking back, it was a bit careless. In 2010 I was on the tube and picked up a newspaper and read that the guy who had done the murder had been murdered in prison with a lump of rope. I have no idea if the killer had ever heard the record or not and I didn’t care that he had killed him, but I felt complicit in something horrible. Like I always said about Blank Generation, we got everything we asked for in that band, good and bad.

Chez: Yeah, I’d echo what Benny says. Child murder and abuse is unforgivable, the worst of the worst crimes. If he’s dead that’s one less bastard to worry about, but I don’t support capital punishment. Also, you see the likes of the family of the drummer soldier [Lee Rigby] killed by the Islamic extremist asking people to stop using his name to make political points. It’s horrendous and things like that make you justifiably angry. But as Benny says, it wasn’t our place without the consent of the family to use his name in that song.

In general, though, understanding how young the band was is important. The first gig Kneill just turned 15, I was 15, Don was 16 Benny might have just turned 19? We were kids full of cider, speed, LSD and pot throughout all of it.

You don’t agree with the death penalty bit anymore?

Chez: I don’t support it, cos I don’t and would never trust the justice system.

Benny: Once you give the government the freedom to kill, they aren’t going to stop at just the people you think they should kill.

I used to be on the fence about it, but I made my decision after watching Dancer in the Dark. Björk portrays a Czech immigrant working in a US factory, and there’s a grim execution scene towards the end. After I saw that, my mind was made up. I know it sounds silly, but that’s how it was.

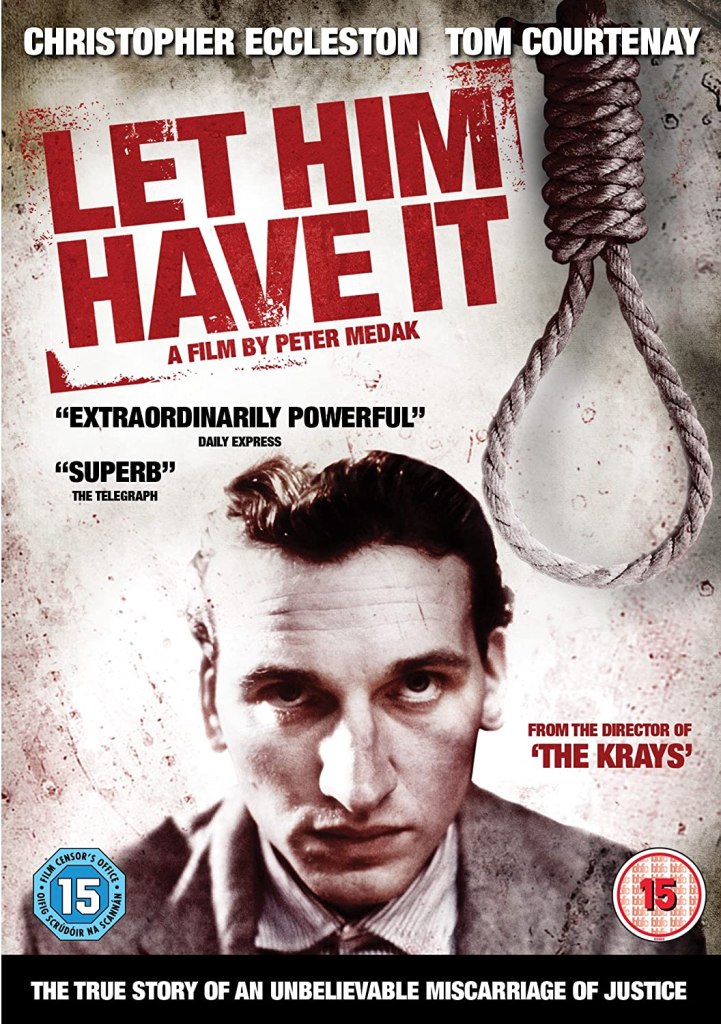

Benny: Watch Let Him Have It, about the Craig and Bentley case in the 50s. They were two boys who robbed a sweet factory. One was autistic, the other was a wannabe gangster who had a gun. When the police came they asked for the gun. The autistic boy said let him have it, bur the other kid shot the copper. Because he was underage and couldn’t be hanged, they hanged the autistic boy instead. Arthur Kay from The Last Resort did a lot of campaigning to get him pardoned. [there was a 45-year-long campaign to win Bentley a posthumous pardon – Editor]

THE ALBUM

Then, in 1994, came the album, Out Of My Head.

Chez: The album I actually really love as a piece of music. It was mostly written over a very short period of time and all based around the song ‘Out Of My Head’, which appeared on British Oi! Working Class Anthems and was in my opinion the best track we’ve written, though I prefer the British Oi! version and recording. Not sure if you’ve heard the cover by a Russian band called The Zapoy, who I thought did a great version of it.

We recorded the album over three days in Watford and were lucky enough to have our pal Darrel Smith from The Hoopers/Cock Sparrer with us for the full three days, helping as a technician and advisor. The album is really the story of what it’s like to be young, growing up in times of deep division, high unemployment, looking forward and seeing no road that makes any sense. So just end up taking drugs, drinking, getting into trouble and generally being bored, angry and confused. It was never really planned but I love the dystopian feel around our sound and the album. We were listening to stuff like The Exploited, Subhumans, GBH, Discharge, a lot of UK 82 punk, along with The Rejects, Cock Sparrer. We’d just be taking speed and acid all weekend, sitting up and just hammering these records.

And the lyrical themes?

Chez: There’s a lot of conflicting and confused messages in the record, but I’m OK with that. I think people that have a handle on the world from a young age are lucky. You don’t have to understand everything from the day you’re born and you don’t have to be defined by your thoughts whilst you try to figure it all out. The standout tracks for me are ‘Violent End’, ‘Blank Expression’, ‘Clockwork Nightmare’ and ‘No Consolation’ but I think most of ‘em have their own charm. I thought Kneill’s guitar sound and solos on that album are magnificent and really drive the album.

The cover shot was taken by another friend of ours John Hooper/Zimmerman, who was the front man of The Hoopers. I don’t think we could have asked for a better photo than that: captured us perfectly, fucking around in Benny’s bedroom looking serious and not serious, Pistols poster on the wall. Top photo.

Benny: A fact about our album. Johnny Hooper told us if you wanted your recording to have that hearty Oi sound, you needed to eat something heart the night before you went into the studio. I dunno if you still can, but then you could buy hearts in Tesco, so I would buy a pack and cook ‘em up. Not sure if anyone else ate any hearts, but I always did and it always seemed to work. I dunno if Johnny was fucking with us or not, but he claimed The Hoopers always did it.

84 Records reissued the album in 2008?

Chez: Yes, and the re-release of the album was the only time there was any talk of a reunion gig. We were offered a big European festival and decided we’d do it, but that fell through. So we just re-recorded ‘Violent End’ since we were together, and it turned out pretty good. But the two previously unreleased tracks ‘Why Does Feel’ and ‘I Got Nothing’, recorded in a shed in ‘94, were cracking songs. Probably two of the best songs we’d written since ‘Out of My Head’, but unfortunately not the best recordings. It’s a shame things panned out how they did, cos we could have written and recorded a lot more – but that’s life.

LIVE AGGRO AND DEMISE

Chez, I remember you mentioning a few years ago that you had stiff-right-arm types showing up at some gigs. Did the far right have a lot of clout on the London scene?

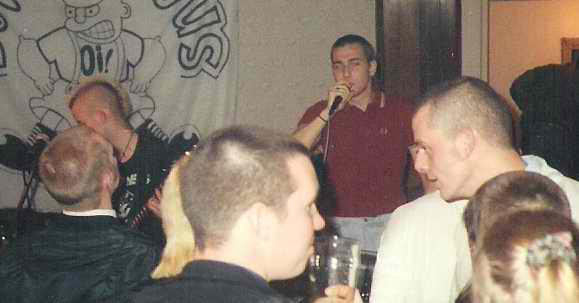

Chez: Oh yes, it did. After British Oi! and the single came out, we were getting booked in a lot of places: The Stick of Rock in Bethnal Green, over in Norwich with Braindance, up north with the Pressure 28 lads, to name a few. And loads of really decent gigs in Wycombe with The Blood, The Hoopers, The Elite, Argy Bargy and many more. These were good old Oi gigs and we had a lot of fun.

But when we did a night in South London, it was a different vibe completely. It was a pub in the Old Kent Road called The Lord Wellington, which for some reason was known as the Henry Cooper at the time [The pub was in 512–516 Old Kent Road, right between Bermondsey and Peckham – Editor]. A lot of far-right business going on, people quizzing us directly about “our politics”. I remember having a disagreement with ‘em about whether the Germans were brothers. I was all about the football and was still listening to war stories from my nan about the Blitz. When they started talking about Aryan brothers, I was like, “what the fuck is he talking about now?” We weren’t thinking like that, we were mostly full of contradictory bravado. For the record, I love Germany and the German people. It was purely 20th century British mentality, indoctrinated into an angry teenager, nothing personal.

Yeah sure, “one world cup and two world wars” type stuff.

Chez: We did know people round our way who were politically dodgy as fuck, but we mostly thought they were idiots. I think up to then I’d been exposed to what I’d call playground politics. But this was the first time I’d met face-to-face people who were organised, clearly extreme, and along with that I felt they were very dangerous. We done the gig, went down very well. We were pretty pleased with ourselves when we left. We took it as “we can go anywhere and do anything” – that kinda attitude. We were very naive, but becoming a decent band. We knew it too – I mean, we knew when we were shit as well.

A short while later was our album launch at the Nags Head, High Wycombe, in the Blues Loft, where it all began when we were nippers. That night a good 200–300 people turned up, which was unheard of for a pub Oi gig at that time. Upstairs and downstairs packed. You could notice a lot of far-right faces and tattoos and what comes with that: a lot of heavy atmosphere.

There were loads of other people as well. Mates of ours, people who’d come down with the other bands and so on, but generally, everything pointed to something special in a packed-out venue. Anyway, we went on and got about a minute into our opening track, then it was drowned out from the back with the old ‘Sieg heil’ and ‘N***** n*****, out out’. Then the whole place erupted into violence, bottles smashing, fists flying. We stopped playing.

Next thing I see is our good pal Lorp, the guitarist from The Hoopers, stood in front of us covered in blood, looking like an Oi Jesus with his long hippy hair and covered in claret. He’s been bottled, glassed, beaten… something I’ll never forget. And he said to me “Kevin’s still in there”. The feeling in my guts at that point I can’t explain. Kev was a black geezer, big fella with dreadlocks, a mate of ours. Basically, these two friends of ours just walked in to watch us play, like they’d done countless times before when we’d played in Wycombe, but usually it would just be with our Wycombe pals and they would have known everyone in the room.

We got Lorp out the back door along with our old man Spike, the only other longhair in the place, and I went to try and find Kev. Thankfully he’d managed to fight his way out. By now there were loads of other fights breaking out around the place for whatever reason. I found Kevin downstairs. He was so angry, he wanted to wait to get ‘em. He was still ready for action, which I still find inspiring. But I told him to go and get safe. We packed up and left.

Bloody hell. And after that?

Chez: Blank Generation did one more gig. We were booked to play in Norwich with Another Man’s Poison and Braindance. A great night. But essentially, me and Benny were done. It all weighed too heavy. I felt, rightly or wrongly, a level of responsibility for that night at the Nags. Everyone there was there to see us, and one of those lads could have easily got killed that night. And for what? Cos one of ‘em was black. It doesn’t bare thinking about, but I thought about it a lot. We had offers of gigs which the band had differences of opinions over, as to the direction of who we were, and so the band split and we did different things.

Such as?

Chez: Benny and me started another band a bit later called Rumpleteaser. It was us with Don, the Blank Generation drummer, and Boswell the vocalist from the Gasmasks – so there was two vocalists – and on guitar was a guy called Jim. Kniell from Blank Generation and even Lorp from The Hoopers played guitar over the life of Rumpleteaser. We recorded much less music than Blank Generation. But we wrote a lot of songs and got back to just having a laugh, getting hammered with ya pals and having a say about any old bullshit that pops into your head, while ya mates smash out a load of punk rock noise. We had no direction, no affiliations and didn’t give a fucking shit… that’s right.

Benny, you can be seen with your then-girlfriend at the end of the Channel 4 documentary World of Skinhead (1995). How did that one come about?

Benny:The World Of Skinhead was made by George Marshall of Skinhead Times. Gavin Watson brought him to Wycombe and told us to meet in The Anchor, a pub we used to frequent in the town centre. It had been the Wycombe skinhead pub during the 80s and the scene of a riot in about ‘86 I think. We used to drink there because it was a proper pub with a proper landlord. We tuned up there that Saturday afternoon and in walked one of the Wycombe punks, a guy called Mad Keith, dressed in full nazi uniform. I just thought, “fucks sake, Keith”. He wasn’t even a skinhead or a nazi, just had an interest in WW2 stuff. In the 80s, he had a WW2 German motorbike and sidecar – people used to try to run him off the road.

BUT LIFE GOES ON

Moving on to the end of your skinhead days, I remember Benny saying once that he stopped being a skinhead because “fuck hate”. Was it a hate-driven movement for you?

Benny: There was a lot of hate around in the scene. Nowadays I would rather spend time with people who talk about the things they love rather than the things they hate.

Fast-forward two decades, and you’re at the Elephant’s Head pub in Camden, telling Trevor of Crown Court that there’s no point in reviving Oi…

Benny: Yeah, I first met Trevor in the Elephant’s Head after a Toy Dolls gig in Camden. I went with my friend Maxie, a wonderful German skinhead girl who I met way after my involvement in the scene. She had been putting on skinhead events at T-Chances in Tottenham, including a Crown Court gig. She introduced me to Trevor, and because I was pissed I started on like: “What you doing Oi for? It’s over, it’s redundant… it’s only still a thing because of a lack of embarrassment”.

A few months later I went to The Great Skinhead Reunion in Brighton and Crown Court were on the bill. They fucking blew the roof off. I went up to Trevor afterwards and said “that was awesome, mate”. He said, “I’ve met you before, haven’t I?”. I said, “Oh yeah, Elephant’s Head. I got on your tits, didn’t I? Sorry ‘bout that, you certainly showed me tonight”. Crown Court reignited my love for Oi and I went to a lot of their gigs.

We’ve talked for a long time and should probably draw to a close soonish. You were both staunch supporters of Jeremy Corbyn, so I could ask you about that.

Benny: Yeah, I was a big supporter of Mr Corbyn. Of everything that has ever been levelled against him, the one thing they could never pin on him was that he was a liar. A politician who didn’t lie and always gave a straight answer, whether you liked it or not – the English were not ready for that. I had always been a Labour voter my whole life, and that was our last chance. We are fucked now for generations. Sir Starmer is there now to destroy the Labour brand to make sure nothing like that ever happens again.

Despite all this, would you describe yourselves as patriotic?

Benny: In the Blank Generation days we were flag monkeys and probably would’ve voted Brexit had it happened then, but I felt I had an inside knowledge of what a con that flag bullshit is. It never leads to anything nice.

Chez: I’m not so sure about that. We were always staunchly anti-Conservative, anti-Royal. Early days we were very class war-influenced and anarchic. We’d grown up under Thatcher, and the inequality and the attacks on working-class communities by the Tories were the driving force of our anger more than anything. And Brexit is a Tory piece of work. So I would never have got into bed with them under any circumstances. But yeh, we were very British bulldog, Union Jack, football kind of bravado. We had no game plan in the political arena – just angry at most things from being poor, disillusioned and out of opportunities. But Benny’s right: we got to see a lot of how things work in terms of the lies, conspiracies, the bullshit, and how destructive certain ideologies can be even at a granular level

OK, but I meant more small-p patriotic in the sense of wanting your country to be a good place to live etc. Is there hope?

Benny: The UK is fucked. Mr Corbyn was our last chance of any decency. The UK is a bleak, Orwellian, dystopian landscape and is getting worse all the time. When we lose the National Health Service completely that’s it, the UK as we know it is done. I have very little hope for us now.

You’re both National Health Service workers, right?

Benny: Yes. I love the NHS and everyone who works so hard to keep it running. It’s not an easy job.

Chez: I don’t think the UK is unique in its situation, I think the rise of far-right politics into mainstream politics is a problem for most countries now. It’s so heavily funded by rich faceless billionaires and oligarchs. All this online conspiracy theory bollocks got loads of normal people thinking they’re a class warrior while ushering in some real darkness. Not pretty.

As for being patriotic, in terms wanting things to be better, specifically for the working class, yes why not. The problem is we have people like the Tory party who wrap themselves in a flag, but couldn’t give a fuck about the people or what’s best for them. I think the working class in Britain had a post-war contract of what they should expect, but that’s all been taken away. I felt Corbyn was the opportunity to put that contract back in place. But that chance has gone.

Well, something will have to give eventually. Have you stayed close to the music scene since the demise of Blank Generation?

Chez: We did a lot of parties/raves throughout the 2000s – sound system DJing. Good times. I still write and produce music in different styles – punk, breakbeat, hip-hop, I’ve got a number of tracks which I hope to get the right people involved in at some point. Rumpleteaser became a real mix of sounds like the band Pitchshifter or The Prodigy. I like a mix up of styles. Hopefully I’ll put some bits out at some point, but at the minute family is the most important thing to me.

Benny: I’ve been running an online radio station, Cutters Choice Radio, for the last 12 years. I started it with my mate Xavi, a Barcelona skinhead and lead singer of The Aggronauts, whom I met while he was living in London. We were going to start a punk band called Cutters Choice, but that eventually materialised as a radio station. After he moved to the US I kept it going for nine years playing everything from punk to funk, soul to rock ‘n’ roll, electronic to demonic and ska to the bizarre. Then when lockdown hit, our mate Gerry got involved and recruited pretty much every DJ he’d ever met, and now it’s a worldwide 24/7 station and a great community has grown from it. Kept a lot of people sane during that difficult time. Chez’s show is On the Waterfront, every other Wednesday at 6. Mine is The Benny Fonz MWS Sessions every Wednesday at 7.30.

Thanks very much for the interview, gents – it was a pleasure.

Blank Generation were : Benny (vocals), Kneill (guitar), Chez (bass), Don (drums).

1) what is the problem of antiracist skinheads today with masculinity? macho and proud! masculinity and biology are not sexism. feminism is sexism and misandry (valerie solanas)

2) not everyone with long hair are hippies (I even know serial killers with long hair)

3) the working class around the world needs solutions not patriotism.

4) skinheads say they are “politically incorrect” but lyrics about serious crime scare them. if they heard the lyrics of many grindcore groups or punk artists like ggallin they would be crying hahahaxD.

I don’t read answers.

LikeLike

Another great interview, to be honest I barely remember Blank Generation except as a compilation band, so I’m going to track down their material later, always cool to read interviews with this type of introspection.

LikeLike

Don and Kneill did The Burning with Little Charlie from AMP. Songs were on More Working Class Anthems.

LikeLike

Brilliant interview! Took me right back.

I saw a couple of really early Blank Generation gigs in summer ’90 when they were a five-piece and covered the theme from ‘Bod’, utterly shambolic but really good fun. Later on my band supported them at the Morning Star, I reckon around April-May ’93. By then they were a tight unit with decent songs, all wearing ‘Clockwork Orange’ gear iirc, and they even turned Chez’s bass amp on 😉.

In a town that had more than it’s share of mediocre middle-class US-style ‘punk’ bands, Blank Gen stood out for their integrity, passion and determination. They were the real thing and I’m glad I was around to catch them.

Only really knew Kneil – he’s responsible for my first tattoo, much like dozens of other Wycombe people my age. Benny was always friendly and approachable, though, while Chez and Don were the quiet ones.

LikeLike