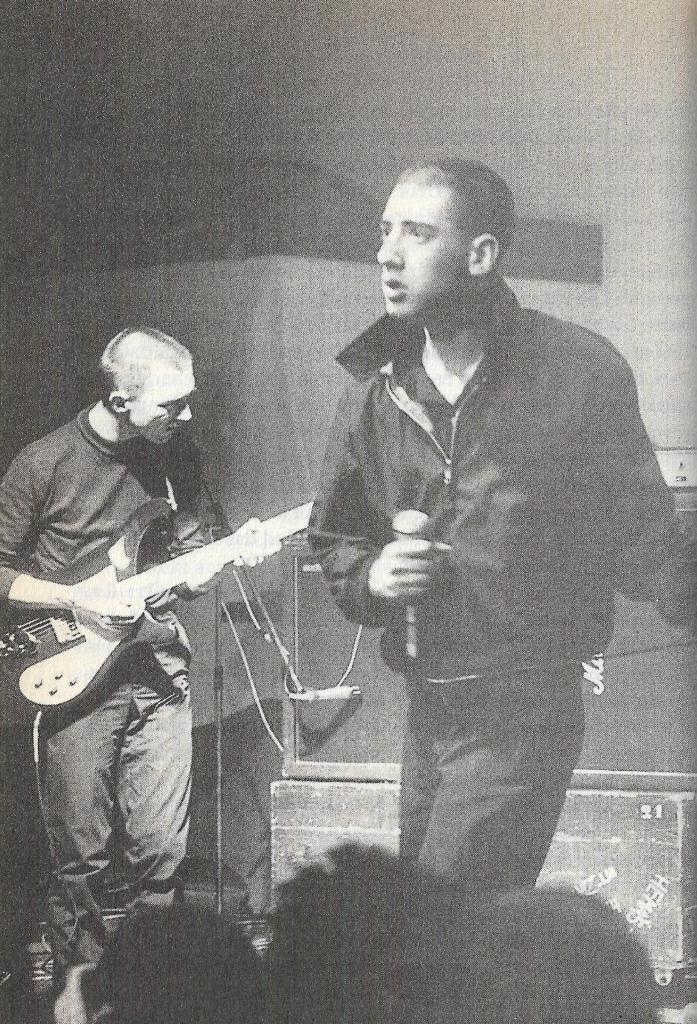

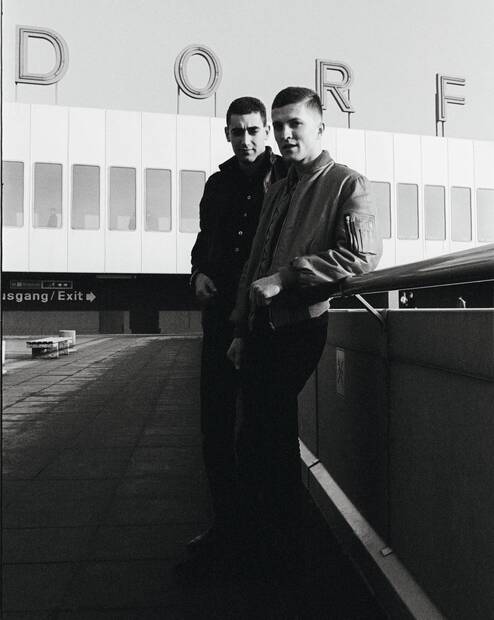

DAF (Deutsch-Amerikanische Freundschaft, meaning German-American Friendship) were a post-punk, post-industrial, proto-EBM band that emerged from Düsseldorf’s early punk scene, active mainly in the early ’80s. They weren’t skinheads, but their singer, Gabi Delgado-López, had multiple encounters with skins while the band lived in London – some positive, some negative, all of them memorable. He retained a soft spot for the subculture.

I struggle to think of any bands, or members of bands, whose stances on various issues I fully subscribe to. In general, the closer they come to my own views, the more disagreements I seem to have with them – I suppose the saying ‘narcissism of small differences’ applies here. Delgado-López stands apart: I can’t recall him ever saying anything I did not think was spot on – whether on politics, social issues, or on questions of attitude and values beyond politics.

Gabi Delgado-López passed away in March 2020. Here’s an excerpt from an interview he gave to Judith Ammann for her book Who’s Been Sleeping in My Brain in October 1983.

Matt Crombieboy

“Sub-groups often develop their own language. That’s what gives them their own distinct feel and lets them build their own pride. Skinheads, for example, speak in a way others don’t understand. It’s like a secret language, and that’s important for identification. (…) I do think that people who came to DAF concerts, at least in the beginning, had their own culture, their own identity, their own language, their own self-confidence, and from that they drew their own strength.

This also has to do with dignity. ‘Dignity’ might sound old-fashioned, but I think it fits. ‘Pride’ is also a word that feels right here… Not taking shit from others, because you know you’ve got your own world, and you’re not going to let them take it away from you.

In New York, many people have this ‘street dignity’. They’ll go nuts if you step on their shoes, because now their shoes are dirty, and that hurts their dignity, their pride. I think that’s how it’s ought to be. It means you’ve got a clear sense of who you are, even in situations where it isn’t really that important (they’re just shoes, after all). It’s simply a kind of pride that says: ‘This is what I am, and if someone tries to attack that, I’m ready to defend it, because I’m proud of it’.

Another example: back in the day, there was a real working-class pride here in the Ruhr region, which isn’t really around anymore. That working-class pride created something important: solidarity. People were proud to be workers and felt like a group with demands they wanted to push through. Today most people try not to be workers at all and instead prefer to belong to the levelled masses the best they can.

More than for anyone else, it’s important for those who want something different – those who are, let’s say, underprivileged – that they say: ‘We see ourselves as a group, and these are our symbols’ – symbols play a huge role – ‘and woe to anyone who dares to touch these symbols’. So, you shouldn’t say ‘I’m a poor loser’, but ‘I’m the strong other’.

Take the Turks as another example. Right now, the Turks in Germany don’t dare to show themselves as Turks, except in their ghettoes. When you’re underprivileged, you have to insist on your identity, almost elevate it to a symbol and say: ‘All the more now. We’re one hundred percent Turkish. That’s right, we’re the Turks!’ – enough to scare the Germans, so they realise they can’t treat the Turks however they like, because the Turks will fight back.

When it comes to these things, I find violence perfectly legitimate, precisely to preserve your dignity. I wish many people who see themselves as victims would instead present themselves as heroes, appearing so dangerous that others start to fear them. For instance, when I see a peace demonstration today, the police have a more heroic style than the protesters. Something’s wrong there. Victims who from the outset define themselves as victims – through their clothes, through their expression, through their sense of suffering – will hardly ever achieve anything.

That’s why I find this confidence so important, even if it’s exaggerated to the point of near-parody. The most important thing is that you feel strong and proud and take no shit, because that creates fear, and they realise it will take a lot more to put you down – and I don’t mean scraps, I mean the media. If you show pride, they are more cautious in how they treat you.

The provocateur must never be weak. Otherwise, his sole function will be to give them someone to point at and say: ‘Look at him, he’s against everything, but he’s unhealthy, fucked up, weak’. The provocateur has to be a hero. Just look at Che Guevara: why does his poster hang everywhere? A fundamental part of it is his pride, his style – he looks like a hero. People in Germany don’t understand how important that is”.

spot on

LikeLike