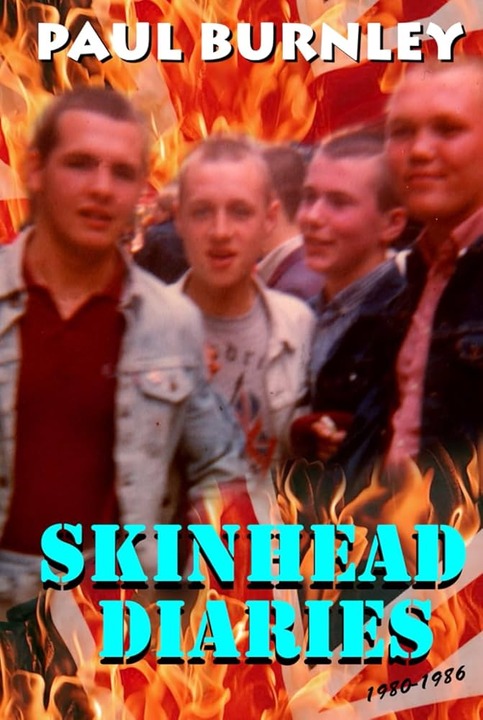

Paul Burnley: Skinhead Diaries 1980–1986. A Coming of Rage Story

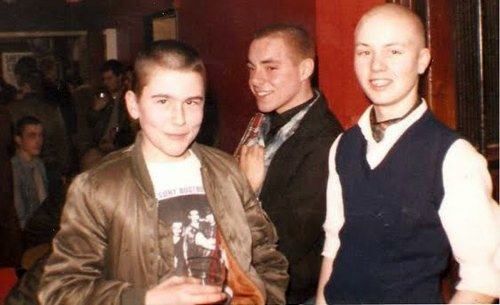

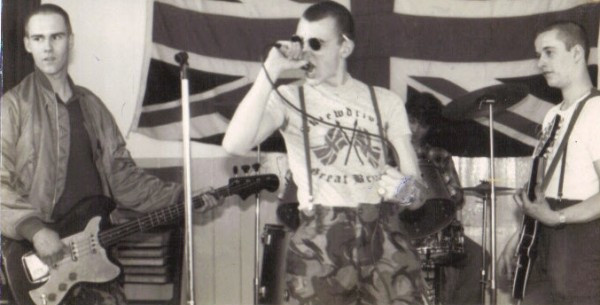

This book is the first part of the autobiography of Paul Burnley – in reality Paul Bellany, son of the famous painter John Bellany. As most readers will know, Burnley was briefly the vocalist of the National Front skinhead band Public Enemy from Maidstone, and later the singer of the London-based No Remorse – one of the most self-consciously extreme nazi bands on the Blood & Honour scene. This volume, however, covers his teenage years before he joined No Remorse – roughly 1980 to 1986 – when he became a ‘rudeboy’ and then a skinhead, quickly drifting to the far right under the influence of his mates and various formative experiences.

Skinhead Diaries is self-published through Amazon, so much of the dosh is going straight into Burnley’s pockets. You may ask why I handed over my cash for the book, and why I’m helping promote it on this blog? To answer the first question, curiosity got the better of me. All things considered, I found it unlikely that my money would go on to fund some far-right terror cell. More plausibly, I’d be buying a retired ex-nazi a few pints. If that makes me morally complicit, so be it.[1]

To answer the second: because I hate hypocrisy. The book exists, for better or worse. Some will read it but keep quiet about it so as not to ‘advertise’ it – because, as true ‘anti-fascists’, they assume the average person lacks the critical faculties they themselves possess. It’s an elitist censor’s mindset that I despise – but also one that ascribes quasi-supernatural powers to words, making the opponent seem bigger and more powerful than he really is.

As for Burnley, he presents himself as someone who left politics in the second half of the ’90s, though some argue he’s playing both sides. If you want to believe he’s done with the right, you can – but if you prefer to think of him as the same old bastard deep down, he’ll drop just enough trollish hints to help you sustain that belief. My own impression, based on little more than a few choice keywords in the introduction – ‘cancel culture’,[2] ‘virtue signalling’, ‘fearmongers in the media’ and the like – is that he may have wound up somewhere in the Torysphere bubble occupied by the Telegraph, the Mail, and their stunted culture-war cousin, Spiked. But that’s just speculation.

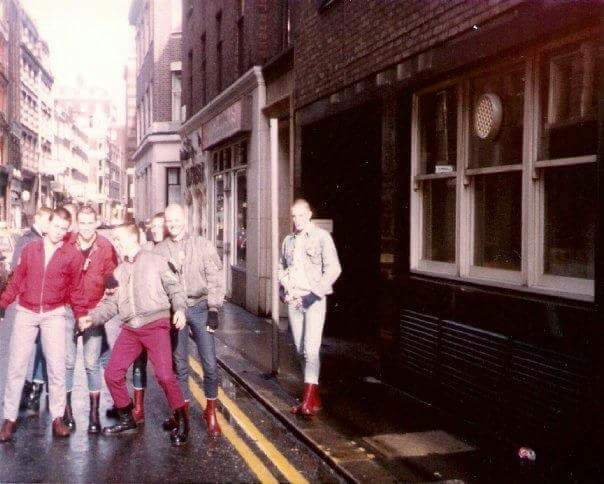

What’s the pull of this book, then? For one, it’s set in London – but not the one you know now. Burnley grew up in Battersea. Today it’s a stomping ground of yummy mummies, BBC6 dads, and poodle-walking American diplomats. Back then, it was a different kettle of fish. Historically an industrial working-class area ruled by the shadow of Battersea power station (as seen on the cover of Pink Floyd’s Animals), it was in steep urban decline by the 1970s – a downturn linked to the collapse of heavy industry and dock work. Economic hardship and unemployment plagued the borough, as did crime and social problems – including simmering racial tensions, the backdrop to much of this book’s story.

CONCRETE JUNGLE

In his book, Burnley refers to himself as an ordinary working-class lad, but the reality is more complicated. His parents were divorced: his father, a struggling painter and bad alcoholic, only came into money in the ’90s. His mother, with whom Burnley lived in a modest flat without central heating, sharing a room with his brother, was an art therapist working in prisons and friends with people like the Sex Pistols’ graphic designer Jamie Reid. You could say his family background was a kind of declassed bohemia – culturally middle class, but materially squeezed into working-class conditions. Burnley calls his accent ‘cockney’ – but listen to the audiobook and you’ll hear a blend of broad South London softened by Estuary English, mirroring these blurred class lines (of course, his accent may have mellowed over time).

Other than that, Burnley’s early teenage years played out like a blueprint for the London skinhead experience circa 1980. It all kicked off with 2 Tone and high-adrenaline gigs by Madness, The Specials, the Selecter and Bad Manners – and the tribal pride that came with dressing the part. Burnley recalls every outfit with forensic precision: which colour Sta-Prest matched which Ben Sherman on which night is still tattooed in his mind like a regimental code. Even then, a couple of years before Skrewdriver’s infamous ‘coming out’ gig, there’s a strong right-wing element in the scene. When the Specials namecheck the National Front in ‘Concrete Jungle’, stiff-arm salutes shoot up across the Hammersmith Apollo. And whenever the DJ drops the Harry J All Stars’ ‘Liquidator’, a crowd chant of “Skinheads are back, Sieg heil!” becomes the chorus of the track – a ritual that would all but become a piece of London skinhead folklore.

We never gain much insight into how some of these skins squared their love of Jamaican music with white supremacy. A few years later, when Burnley attends a reggae night at the Crown & Cushion pub – a riverside hangout for London’s nazi skins in Woolwich – his explanation goes no further than this: “There’s no hiding from the contradiction about being a racialist skinhead that loves the infectious sounds produced by black musicians from the Caribbean island of Jamaica. It doesn’t make sense really, but when you’re jumping around with your mates (…) to the sounds of ‘Suzanne Beware of the Devil’ by Dandy Livingstone, ‘Pressure Drop’ by Toots and the Maytals, ‘Monkey Spanner’ by Dave and Ansel Collins and a whole host of other Trojan hits, I don’t care, because it feels great”.

This is Burnley’s core device throughout the book. There’s no hindsight, no commentary from today’s point of view, no reflection – just Burnley’s unfiltered teenage mindset, conveyed in the style of a diary. As he lays out in the intro, this is to avoid constantly justifying and condemning himself, which would have gotten in the way of the narrative flow. On one level, that’s fair enough – we’re left to make our own assessment. On the other hand, our understanding of the period would benefit from the bigger picture, which tends to emerge only when certain dots are connected in hindsight. The ‘raw, unfiltered’ premise hides as much as it reveals.

This approach also hands Burnley a kind of narrative free pass. By sticking to his teenage perspective, he gets to recycle the worldview he held back then, shaping events to fit and quietly sidestepping anything that might complicate the picture. The result is an extremely partial view of London, Battersea and the skinhead scene, presented as the way it was. Were there really no apolitical, non-racist, or even left-leaning skins in London? No multi-ethnic mobs? And those sieg-heils at 2 Tone gigs – wasn’t at least some of that teenage posturing, a bit of adolescent wind-up? For Burnley, if an Oi band takes no political stand at all, this can only mean it’s hiding its right-wing politics. When recounting the Skinheads documentary featuring Combat 84 on the BBC, Burnley diligently passes on Chubby Chris’s racist tirades – but keeps quiet about bandmate John Armitage’s anti-racist statements in the same programme. Seen through Burnley’s selective lens, the whole skinhead cult just looks like one seamless rite of passage into full-blown neo-Nazism.

The only time skinheads of a different stripe surface in his narrative is fleeting – when the Redskins hit the stage at the GLC’s ‘Jobs for Change’ festival in Jubilee Gardens and are set upon by Burnley and his nazi mates. But we’re swiftly informed by the teenage Burnley that they aren’t real skins – they’re imposters merely “posturing for the cameras” and “bringing the skinhead name into disrepute”. Left to stand without reflection, these throwaway putdowns go unchallenged – but they shouldn’t. Didn’t Skrewdriver become a skinhead band on their record company’s advice back in ‘77, “posturing for the cameras” in dubious clobber? While I can’t vouch for every member of the Redskins, Martin Hewes had been a skin for years by the time the band formed. If sixty-something Burnley allowed himself a moment’s hindsight as an author, he’d have to acknowledge as much.

ONE LAW FOR THEM?

The same narrow viewpoint shapes Burnley’s treatment of racial conflict – which, by his own account, was the main reason he became a nazi. Again and again, he recounts mistreatment at the hands of black youths: from being bullied at school to the fatal stabbing of a skinhead mate by a gang of Rastafarians in March 1984 – an attack where the victim’s pregnant companion also lost her unborn baby. In every case, Burnley points to the supposed leniency shown to the perpetrators by teachers, parents, the state and the media.

Here, Burnley’s framing actually has its use. It helps us see how many skins – and not just the nazis – understood these issues back then. It’s all there in the 4-Skins’ ‘One Law for Them’:

Go to football, throw a brick

Get no mercy, months in nick

Riot in the ghetto, red alert

Guilty free, innocent hurt

We’ve been warned of rivers of blood

See the trickle before the flood

Pretend nothing happened, make no fuss

One law for them, One for us

Unless your name is Gary Bushell and you wilfully misread the song as being “about class”, the message is clear: white working-class youths get months inside for minor offences, while the law looks the other way when black youths riot, leaving innocent people hurt – the ‘rivers of blood’ line referencing Enoch Powell’s infamous speech. These lyrics didn’t express some fringe sentiment. They reflected a widespread sense of double standards among skinheads at the time, which Burnley taps into – both as a participant and, now, as a narrator who never quite lets go of that framing.

PRESSURE DROP

The usual liberal anti-racist playbook is to deny there are any problems, shame the racists for being racist, and try to shut them up where possible. But that’s a dead-end strategy, and on this point, I agree with what Burnley says in his introduction: “Cancelling their voice just makes them shout louder and pushes them deeper into their caves of hostility … To disarm that burning hatred you must negotiate the reasons why they ended up there”.

This may involve recognising the kernel of truth in what they say. Instead of pretending that black kids were all angels under siege from racist skins, you need to confront reality as it is. By most accounts, young black males often carried themselves in a confrontational way – just like white skins. Rastafarian gangs didn’t just pick fights with right-wing skinheads; innocuous punks got it too – more so in Notting Hill than in Brixton, according to eyewitnesses. To complicate matters, in the ‘60s and ’70s, some black estate gangs were known to kick the shit out of Asians. When Ian Stuart Donaldson and his apolitical punk band Skrewdriver arrived in London in 1977, he noticed black kids “all seemed to have a chip on their shoulder” – an experience that eventually set him on his path.

Can all this behaviour simply be explained as a reaction to racism? Much of it might have been a warped assertion of dignity in a hostile environment. In places like 1980s London, black people were mistrusted by wider society from the outset – far more likely to be stopped and searched by the police, disadvantaged in jobs and housing, and seen as troublemakers before they even opened their mouths. Nobody said that oppression brings out the best in people – in fact, being pushed to the margins makes you more likely to lash out, as aggression can be a way of rejecting victimhood and asserting control. Over time, a certain culture takes shape, and a vicious circle opens up. At the end of the day, Combat 84’s Deptford John put it best: “We [skinheads] have got a lot in common with blacks. We both get police pressure, we both get spat on, we can’t get jobs, and we get kicked out of places. Except they have a colour they can never change, and we’ve got an appearance that we can change”.

Did black kids pick the right targets for their anger? Rarely. You can invoke structural racism or the legacy of empire – but at street level, none of that matters. No one’s going to accept being hassled or beaten for something they had no part in, let alone when it was set in motion by a different social class before they were even born. Working-class blacks were up against systemic racism, police brutality, and daily discrimination. But their white counterparts faced deindustrialisation, poverty, media humiliation, and street violence. They need to be heard too – not written off as ‘privileged’ because they’re white.

GUILTY FREE, INNOCENT HURT?

What about the idea that blacks were treated more leniently? The facts say otherwise: they generally faced harsher police scrutiny and tougher sentences from the courts, and many deaths of black people in police custody went unpunished. That said, political efforts were made to avoid stirring up more racial tensions after riots like those in Brixton, which temporarily led to ‘soft touch’ policing in some inner-city areas. Skinheads noticed and resented this, especially as they were being demonised by society as the worst thugs of all. When Asian youths firebombed an Oi gig in Southall, the entire British press, from the Tory papers to Socialist Worker, saw ‘racist skins’ as the sole villains.

So, as with a lot of things in Skinhead Diaries, Burnley’s version of events only tells half the story. Accounts like his shouldn’t be suppressed or swallowed whole – they need to be read with a critical eye. Not least because Burnley’s fixation on his own victimhood means we never really see the other side of the equation. He’s jumped, chased or hassled by blacks, soulboys, cops, teachers and parents – and this litany of persecution supposedly explains why he turns to National Socialism (into which he, incidentally, never goes in any depth… Mein Kampf? Dismissed as “boring” and too bogged down in high politics).

But what about the victims of Burnley and his crew? Apart from the Redskins gig, the only time we read about skins doling out the beatings is when they stage a revenge attack against soulboys in Charing Cross station. That’s it. Was there nothing else between 1980 and 1986? No attacks on leftie paper-sellers? Black youths? Anarcho-punk squatters? Anti-apartheid protesters in Trafalgar Square? Irish republicans? That’s pretty hard to believe.

THE POWER IS YOURS

Music is central to any skinhead’s life, and although the book ends before Burnley joins No Remorse, it’s packed with musical references – to me, the most enjoyable part of his early journey. From 2 Tone and early Oi (including an account of Combat 84’s first performance opening for the Last Resort) to Skrewdriver’s infamous comeback gig, from punk classics like ‘White Man in Hammersmith Palais’ to new wave nuggets like the Piranhas’ ‘Getting Beaten Up’, the soundtrack is ever-present. Burnley briefly signs on as vocalist for Public Enemy from Maidstone and pens the track ‘Win or Die’ – but is sacked almost immediately, for reasons that remain unclear. With England’s Glory, Public Enemy would go on to record a very solid Oi album and a few standout tracks for the No Surrender NF fundraiser compilations – musically tight, lyrically moderate. All without him, though. Had he stayed, it might have been the best thing he ever did.

Which brings me to my last point: No Remorse. I know they aren’t discussed in this book, but since I doubt I’ll be penning another review when the second volume rolls around, let me sketch out my view here. To me, No Remorse was a dreadful band. This isn’t to say that far-right music is automatically bad – everyone knows that’s not true, and pretending otherwise is transparently insincere. But No Remorse truly sucked. I know people who think otherwise, so I put their ‘classic’ album This Time the World and follow-up See You in Valhalla on my phone and gave them another go, in case I’d missed something the first few times around. ‘Smash the Reds’ is reasonably catchy in a Ramones kind of way, and the same goes for ‘Hold On South Africa’. ‘See You in Valhalla’ might have been decent if it didn’t plod along at 20 mph. The rest? Still unlistenable – generic riffs, zero songwriting instinct, all papered over by being lyrically ‘extreme’. It only gets worse on the later albums, which stray further from Oi and try their hand at rock – though without Skrewdriver’s skill.

As I was walking home the other evening, ‘Bloodsucker’ came on my headphones. It’s a nasty little rant about a “filthy Asian in his corner shop” who “bleeds our nation of all he can” by “selling his goods at double price”. Burnley incites the listener to “ignore his pleads of mercy” and “burn him to the ground”. What hit me most was how bleak and barren it all felt. Unwilling to endure all of No Remorse’s opus magnum in one sitting, I eventually switched over to the Redskins album. What difference that made! “Let’s get this situation sorted out”, crooned Burnley’s erstwhile nemesis, Chris Dean, and as the horns swelled he reminded me that “the power is yours”.

All the lyrics were spot on – full of hope and defiance, urging us to take aim at those who really hold the power to make our lives hell. Meanwhile, Burnley’s idea of fighting capitalism amounted to impotently venting against some corner shop owner supposedly selling his goods “at double price”. Talk about a fool’s political economy – and a dead-end mindset.

DON’T LET THEM PULL YOU DOWN

Burnley was kicked out of home at 15, left school with nothing, and spent the following years doing things he now says he can no longer recognise himself in: “How on earth was I ever that young lad shouting racial obscenities from the stage?”, he asks in the introduction, “with a dedication to something so completely alien to the life I lead today?” It wasn’t until much later that he got an education and became a “positive contributor to society”. In fact, my early life unfolded along roughly similar lines – not politically, but in terms of circumstances. Burnley isn’t proud of everything he did as an ignorant kid, but he does “not regret becoming the man I am today”. I can relate to that – on both counts.

Despite his turn away from nazism, I suspect there are still many miles between him and me politically – I’m an incorrigible red, and I don’t accept that all ‘extremism’ is the same, as he seems to imply in the book’s introduction. There is extremism that only adds to the stockpile of idiot hatred in a world that already has more than enough – and then there’s extremism that aims to break vicious circles and put ordinary people in charge, in control of their own lives.

On a purely human level though, if Burnley has really liberated himself from his “burning hatred” and found a “productive and fulfilling life”, as he says, I wish him well. What’s more, his avowed refusal to extricate himself by “informing on people” who were doing exactly what he was doing – and over whom he says he has “no moral high ground” – is honourable.

Despite all the shortcomings in how the story is framed, Skinhead Diaries is a useful primary source reflecting the mindset and conditions of a specific time and place, even if limited and biased. The purpose behind it – beyond the commercialisation of Burnley’s past – is not so clear. But if you switch your brain on and read critically, you’re bound to get something out of it regardless.

I just hope that in part two, a little more attention is paid to those whose lives Burnley and his comrades-in-arms damaged – not just to his own victimhood.

Matt Crombieboy

- In fact, I feel far more guilty for giving my money to Amazon, whose CEO Jeff Bezos is causing more suffering than any neo-nazi could in their wildest dreams. Amazon has invested billions in intelligence schemes such as Project Nimbus, used for the surveillance and targeting of Palestinians – and that’s without even starting on how the company treats its workers. ⏎

- I don’t mean to imply that cancel culture doesn’t exist, or that it isn’t a serious cultural problem. In fact, it operates on both sides of the political fence. In recent years, ‘antisemitism’ and ‘transphobia’ charges have been the preferred silencing tools of the right and left, respectively. ⏎

Slowly coming round…a decade from now you’ll have stumbled on the Mirpuri r p e gangs…

LikeLike

Or I might just come across the long list of sex offenders linked to the British far right – especially those caught with child abuse images or grooming kids.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This Eyebrow-Guy who’s built the scene, left the scene (?)- I don’t believe him! No Remorse is the same crap as Skrewdriver… Fck their intentions, fck their oppinions! Fck their apologies and their “sorries”!

LikeLike

None of you guys were there…. I was. Long live Skrewdriver

LikeLike

If you think we got something wrong, or right, or a bit of both, you need to say what. Then we’ll see if we believe you or not. If you aren’t more specific, your anonymous comment is completely useless.

LikeLike

[Right off topic, but the last email I opened before the alert for this was from Baines School!]

LikeLike

oddly my Facebook threw up (sic) a Temu ad offering “Crucified” by Pete Roper. Subtitled “Life in a Skinhead band” (perhaps not so oddly Temu have recently offered a book advocating the anti Semitic Anglo-Israelite cult)

i was intrigued, as this was a new one and I wondered whether Retaliator had shifted their hard core RAC beliefs.

it seems not at all

About

Pete Roper

Bass player and main songwriter for skinhead rock band Retaliator. Both the author and the band have long been slandered, crucified and vilified over two decades by the far-left zombies as being ‘far-right’ for daring to be anti-far-left patriots. Pete categorising himself now as a ‘dedicated truther’ describing his own political stance these days as being way beyond ‘wing’ politics, explaining that his world view has altered greatly in the past five years and he now sees a world tearing itself apart, gripped in a battle between good and evil, with, at the centre of it all, a cabal known as the Illuminati or the New World Order, who are basically Luciferian psychopathic billionaires attempting to completely destroy Christian cilvilisation so as to replace it with a one-world (Socialist) government, a one-world (Luciferian) enforced religion, and a world populated by easily-controlled dull-minded worker-ants.

🙄

LikeLike

That’s a serious downgrade from earlier RAC/fascist rallying calls. Back in the day, the far right at least imagined an ‘ideal world’ – a new social order that would break with the past and deliver true justice. Now the best it hopes for is simply to fend off some imaginary dystopia. Once the threat is removed, things will just go back to how they were before.

Mind you, the same could be said about most anti-fascists today. Sign of the times…

LikeLiked by 1 person

An honest and fair review i must say.

I’m American, half white half black 59 year old skin and as hard to believe as that may be for whoever, i once owned the 7′ single of Smash the reds, and the first Lp ‘This time the world’, in addition to nearly every Skrewdriver release up to After the Fire, and a shit ton of other RAC, Oi! , original Reggae, Punk, Metal etc records- what can i say i love music. Regrettably most of those are long gone, sold to fund bills and surviving tough times. Anyways, we all grow up and things change. Whoever thought that Brutal Attack would one day play in Mexico , or that Bound for Glory would play in Japan, both to very enthusiastic audiences ?

To quote someone somewhere, life’s a trip.

i grew up in a white working class suburb, was in a mostly white gang comparable to what you call Teds, before discovering punk in 81, then skinhead in 84 , founding our own skinhead gang in 85 which led to a near decade of violence from 88 to 98, when i decided to go back to school before i wound up dead or incarcerated. And here i sit thinking about comrades dead from drugs, booze , suicide and gang shit . By the way, my gang was known as fence walkers because we told SHARP & WAR , to pound sand. But that’s another story in itself.

anyhow, cool review.

stay above the dirt!

T F. FCSkins

LikeLiked by 1 person

Paul has since released another volume, and it deals squarely with everything you just mentioned. He isn’t trying to hide anything, from what it seems, and he elaborates on how he feels now compared to them. The man has grown, as any would when faced with such differing convictions, each one tearing him in another direction.

look. He’s no saint, but because he don’t just automatically jump ship, possibly become a Marxist, and/or start grifting by writing and giving speeches about whG he was involved in does not mean the man has t tried to come to terms with a lot of things.

When people change, especially those involved in movements and subcultures that have indoctrinated many a youth, it isn’t the easiest thing to try and outright try and deprogram others, when you are struggling with your own sanity. He owes it to himself before he is able to “owe countless others” whatever indignities he i.poawd on them in public, or just by musical influence. I hope he finds what he is looking for. There IS life beyond the cult, no matter what your political leanings are/were.

LikeLike

gotta say Bingo! on this reply. Exactly what I thought

LikeLike

You can read about all the violence in Eddie Stampton’s soon to be released 2 volume biography, “A Nazi piece of work – the life & crimes of a Neo-Nazi”

LikeLike

I read both volumes.

I agree with what Crombieboy wrote about the first one.

On one hand, there’s an obvious right-wing bias, selective memory, and what looks like revisionism and exaggeration—probably with the intention of normalizing his particular take on skinheads. Basically: “Well, everyone was actually a Nazi, and the ones who weren’t secretly wanted to be but didn’t have the guts.” This frames Nazis as the ultimate skinheads, rather than just one specific subset within the broader scene.

On the other hand, it also exposes some of the perhaps well-meaning but mistaken revisionism from the other side, since far-right elements were, at least initially, much more intertwined with the rest of the scene than most people today would be comfortable admitting. As I mentioned above, though, Burnley applies the same distortion to non-white, left-wing and various other non-far-right skinheads, who were also obviously hanging about at the time.

All in all, it’s a very interesting read. You finish it wanting to know what will happen in the next volume.

The second volume, however, has much less to offer to those who, like me, were more interested in the skinhead angle than in the neo-Nazi craziness. The music part is hilarious, though. The way he talks about the RAC bands as if they were artistically amazing—and that the only thing keeping them from becoming superstars was their political stance—makes you wonder whether he actually believed it and, if he did, whether this blatant proof of insanity could absolve him of his past sins.

Which—spoiler alert—it doesn’t. You keep waiting for the moment when he’ll explain his change of heart and the actual process that led him to abandon racism after it had been his reason to live for more than a decade. But it never comes.

Instead, one day he’s simply not racist anymore. That’s it. What he does explain is how the movement let him down and betrayed him after he had carried it on his back for years. He gets sick of it after being betrayed by former comrades, being threatened, and facing plots from people who wanted to control Blood & Honour, not to mention the conflict with his family.

In the end, it suggests that he became a “normal person” simply because there was no room left for him to live as a Nazi and because he missed his parents—not because of any real education or change of conscience. He just couldn’t be bothered anymore; it wasn’t worth the effort to remain a racist.

Not only that, he never recants his earlier claims blaming Black people—collectively—for his political stance. In the first volume, you can accept this as the “old him” talking. But since there’s no sign of an actual change of heart or mind, you wonder whether he still believes he was justified in being a racist, given that every Black person in London was, apparently, trying to kill him for no reason at all times.

It’s not a bad read and it’s very informative. But you’ll end up with a bad taste in your mouth.

LikeLiked by 1 person