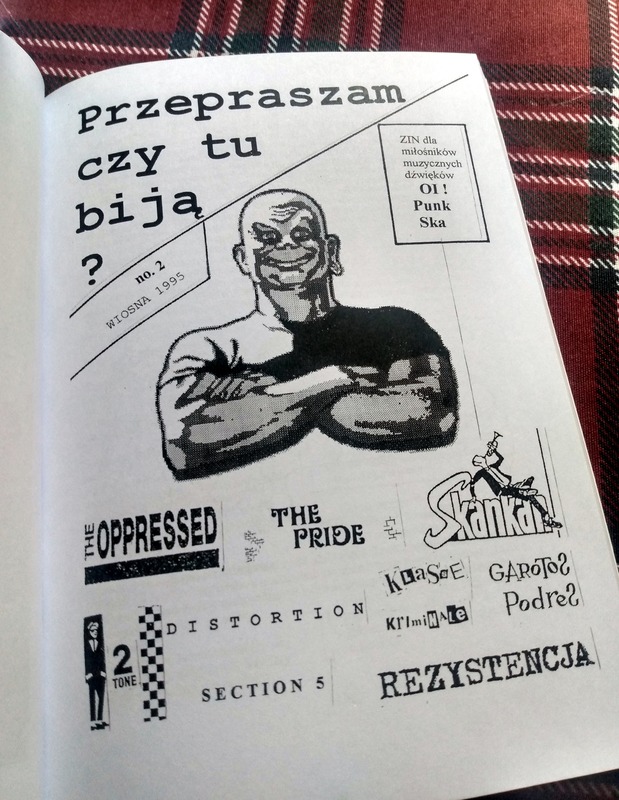

Readers will remember my exhaustive interview about the Polish skinhead scene of the ’80s and early ’90s, and this anthology, published by Bad Look Records of Warsaw (more specifically, Warsaw-Służewiec, which also happens to be the neighbourhood of my childhood), more or less picks up where that interview left off. It contains all issues of the Warsaw skinzine Przepraszam, czy tu biją?, which translates as ‘Excuse me, do they beat up people here?’ and ran from 1994 to 1997 – five issues in total.

The zine was the voice of Warsaw’s ‘neither red nor racist’ but strictly anti-fascist skins. Although SHARP was never promoted in the zine by name, editor Piter reveals in the introductory interview to the anthology: “There’s no point in hiding that our crew was a SHARP crew”.

Just to recap: in the ’80s, Poland had a skinhead scene that was chiefly interested in violence and rebellion, specialising in terrorising punks and metalheads. Although pseudo-fascist posturing was common, skins back then were about as interested in actual nationalist politics as their punk counterparts were in setting up anarcho-syndicalist trade unions. Then, towards the end of the decade, as capitalism was restored in Poland, a quick and drastic politicisation occurred, with three competing far-right tendencies emerging among skinheads: ‘neo-Slavic’, national-Catholic, and neo-nazi skins.

By the mid-’90s, as the nazi skins became the dominant tendency on the far right of the scene, the more ‘organically Polish’ factions – the neo-Slavs and national-Catholics – began to dwindle. But the Polish skinhead scene was also becoming more westernised in other ways, fuelled by Oi and ska revivals taking place across Europe, especially in neighbouring Germany, and the spread of SHARP. The best-known Polish zine of the period, Skinhead Sosnowiec, was workerist and non-racist, but otherwise more or less anti-political.

Warsaw’s Przepraszam, czy tu biją? leaned more towards explicit denunciations of boneheads, though it covered much the same ground in terms of music and bands. We find interviews with the likes of Roddy Moreno, but also with bands that wouldn’t be considered kosher by hardline anti-fascists, such as Agent Bulldog, The Pride, or Rezystencja from Kraków (apolitical, but featuring former members of the seminal nationalist outfit Szczerbiec). The focus seemed to be on just having fun and enjoying skinhead culture without seagull spotters getting in the way – which included trips to ska festivals in Germany and especially to Prague, then a little Oi paradise and, unlike Berlin, very cheap (Propast was a great Prague skinhead and punk bar).

That said, cartoons based on real events, such as one depicting the Warsaw crew smashing up a far-right meeting, suggest there was sometimes more to it than just fun and games. “We had it in with a nationalist crew that had gathered there”, Piter explains, “In hindsight, it was just gang warfare, but with an ideology attached to make it look better”.

Generally, it’s fair to say that western Oi bands queried by the zine all gave predictable, stereotypical replies. More fun are the interviews with Polish bands such as the aforementioned Rezystencja, who, for all their past sins, come out with unexpected and refreshingly provocative statements. Asked if it’s okay for “working-class skinheads to order expensive skinhead clothes from Berlin”, they reply: “That’s a difficult question to answer, given that most Polish skins actually come from the intelligentsia”…

About 1996 or 1997, editor Piter caught Mad Sin opening for Cock Sparrer in Leipzig, and, like many Polish skins at the time, started to drift towards psychobilly – first on the side, then increasingly full-time. The entry of psychobilly into the scene wasn’t viewed favourably by everybody. Warsaw Oi band Triglav – named after a three-headed deity from Slavic mythology – lamented in a song:

The returning wave hits the shore

Like a returning wave, life goes on

Around us, punks turn into skaters, skins turn into psychobillies

But for us, everything stays the same: wine, women and song

The Warsaw skinhead crew began to split into two, three, even four different crews, and it would have been good to read in more detail about why this happened – in the interview, Piter assumes we already know, referring to “the well-known fights” in which everything culminated. Surely, psychobilly alone can’t account for a four-way split?

If you read Polish, Przepraszam, czy tu biją? offers an intriguing glimpse into the Warsaw scene of the 90s. But the absolute highlight of the zine has nothing to do with skinheads directly: a history of Polonia Warszawa, Warsaw’s ‘other’ football team. An alternative to Legia Warszawa, with its notoriously right-wing supporters, Polonia Warszawa was followed by everyone from SHARP kids to anti-fascist ultras. Founded in 1911, it is actually Warsaw’s oldest sports club and was once towering over Legia in terms of popularity.

The most compelling part of the story begins in 1939, when the nazi occupiers swiftly dissolved all sports clubs and closed the stadiums to Poles. Undeterred, fans of Warsaw’s football clubs formed a secret committee that began organising matches in clandestine conditions – initially in the Mokotów district, and later in the more remote parts of Praga, across the river. As many as 50 underground football teams operated in Warsaw and its surroundings. Even under conditions of intensified nazi terror, a second championship was held in occupied Warsaw in 1943, with 10 teams taking part. Polonia Warszawa emerged as the clear winner.

Fans risked a great deal to attend these matches. In the autumn of 1943, Polonia Warszawa players and supporters were ambushed by Gestapo agents at Warsaw’s main central station. Some managed to flee aboard a departing train; the rest were captured and deported straight to the Majdanek camp. Think your commitment to your team runs deep? You could learn a thing or two from Polonia Warszawa’s supporters.

Returning to Przepraszam, czy tu biją? and Poland’s non-racist skinhead scene of the ’90s – what, if anything, remains from that era? Bands like Rezystencja, Triglav, Shrapner and Mauser have long since disappeared. But The Analogs – who started out as apolitical and later began calling themselves ‘100% leftie’ – are marking their 30th anniversary in 2025, and their peers The Real Horroshow have just released a new album. The excellent Oi and ska outfit Podwórkowi Chuligani will also reach the 25-year milestone in a couple of years. And of course, there’s some (relatively) new blood too, such as Łyse Pały from Wrocław, or the more street-punkish Lazy Class from Warsaw.

But while in the ’90s Poland was probably one of the countries with the highest density of skinheads in the world, you don’t really see skins anymore unless you look for them. On my last visit to Warsaw in October 2024, I was informed that the scene there is now about 20 people strong – that’s not many for a city three times the size of Paris.

Perhaps the appearance of an Instagram page named Skinhead Warsaw – which has been posting ‘robust’ graphics like the one below – is a sign of a much-needed revival.

In any case, if you find yourself in Warsaw, make sure to visit Bad Look Records, run by Rodzyn, the good man behind this anthology. Until recently based in Służewiec, Bad Look Records has just opened a new shop inside the Marymont metro station in the north of the city.

The Przepraszam, czy tu biją? anthology is available from Bad Look Records for 50,00 zł – at the time of writing, the equivalent of about 12 EUR.

Matt Crombieboy