The history of a distinct shaved head and boots & braces wearing subculture in Peru doesn’t start until the early 1990s, even though there were isolated sightings during the legendary 80s ‘subterranean rock’ scene in Lima. Economic conditions, isolation and misconceived public notions nurtured a true working-class based skinhead movement, small in numbers, but big in committed ideals. Taking a cue from legit sources, they sought to preserve the original ethos of this movement without ignoring the reality of day-to-day life in Peru. A class-based caste system has been the norm for centuries in this country, and the recent pandemic has exacerbated these differences to a boiling point. The skins in Peru realise that it’s not just fashion and music that fuels them but also protest, whether political dissent or direct action on the streets, that makes this movement a vital subculture dedicated to radical change.

I spoke to Mendo (visual artist and original member of the first skinhead collective in Lima) and Abraham (singer of Ultima Amenaza) about the history and current state of the scene. For more info follow their Cronicas Skinhead Peru page on Facebook.

Freddy Alva

This article appears in the newly released Oi! The Black Book Volume 2: https://urbanstylesnyc.bigcartel.com/product/oi-the-black-book-vol-2

When is the beginning of the skinhead movement in Perú and who are the first skinheads seen in Lima?

The skinhead movement started in the Comas neighbourhood, situated in the northern part of Lima, back in 1993, thanks to the efforts by CRASH Comas (Anarcho Skinhead Radical Change). The northern side is a conglomerate of districts on the northern outskirts near the city centre. During the 80s and 90s, it was a mix of factories and neighbourhoods that were gradually being urbanised and developed, with a large number of migrants from other parts of the country moving in.

The first shaved heads got introduced to skinhead culture through the pamphlet Remember Your Roots, written by SHARP Madrid, which described the real skinhead culture. It had a huge impact on them and they instantly identified with it, especially its working-class themes, anti-racism and class pride. CRASH Comas engaged in various activities, such as comradely gatherings, skinhead parties, jams, pints, etc. The aim was to strengthen the commitment and unity among members.

After a few months, three of these skinheads decided to create the Brotherhood of La Rosa. The objective of this group was to cultivate a sense of belonging and family spirit, based on values such as unity and action, all centred purely around skinhead culture. This group began to meet in different underground scene spaces – places they were already familiar with even before they had shaved their heads – handing out flyers and spreading the lifestyle. Some people were taken aback and cautious, partly because they were misinformed due to negative media portrayals of skinheads. But these early skins’ passion and dedication were stronger, so they carried on with their way of life.

In 1997, this original group of Lima skins crossed paths with another crew known as R.U.K (Kondevilla Urban Resistance) from the San Martín de Porres neighbourhood, which is also on the northern side of Lima. R.U.K. had skinhead members as well, so CRASH and R.U.K. started to work together.

Between 1998 and 1999, a new group called Nosotros was formed, consisting of friends from the National University of San Marcos (UNMSM), CRASH Comas, R.U.K., members of Marginal Force (hailing from the El Agustino district) and people from the surrounding quarters. Nosotros championed clear, tangible ideals while also embracing radical actions.The main ideas promoted by the first skin crews was need to decentralise the underground movement and create spaces in the local neighbourhoods and outskirts. Another objective was to establish a self-managed community, and this idea partly took shape at La Covacha, an autonomous community centre for collective work that was set up in 1999. At La Covacha, we held meetings for discussion, conversation, and comradeship. It was a space where we learned a lot. Today La Covacha no longer exists, but the experiences and stories are not forgotten.

Other ideas they advanced was the promotion of coexistence and the strengthening of loyalty among members. This was achieved through the activities mentioned, as well as other forms of collaboration, such as working together and mutual aid addressing the various needs that might arise within their families. This collaborative ethos reflects the principles of the AYNI system, which was developed by the Incas and is still practiced in some communities. The AYNI system involves mutual support between families, and it aligns with the sense of community and mutual aid that these folks sought to cultivate within the skinhead culture in Peru.

In regards tothe musical arm of this movement, back in 1993, Kontratodo, the first skinhead band was formed. Other bands followed, often with overlapping members who switched roles and members between them. Among these bands were Tropa de Choque (Shock Troop) and Kallpa Oi! Other forms of expression were skinzines and bulletins. The publications circulated during this initial era were: Cambio Radical (Radical Change), Cultura Skinheads (Skinheads Culture), Expresiones Libres (Free Expressions), Resistencia Urbana (Urban Resistance), Desafía (Challenge), NOSOTROS and Reaxxxiona. All of these publications played a crucial role in spreading the principles and activities of the first skinheads in Lima.The story continues with the emergence of new groups, crews and bands. Time has passed since that glorious era, and yet we continue.

Before 1993, Do you know if there were people who identified themselves as skinheads, during the Subterranean Rock movement in the eighties?

We don’t know of any crews, bands or individuals that openly identified as skinheads before 1993, although some who were involved in the ‘Subte’ movement would do later. There were people in that movement who sported elements of the style, such as braces. For example, the band Kaoz shouted “Oi!” and “skincore” during their performances, which you can hear on a recording of one of their shows in Magia. In some of G-3’s artwork, you can see characters with braces and short hair, along with the phrase “skincore”. In the ‘Grito Subterráneo’ video from 1987, there’s a guy from the Matute neighbourhood with boots with a shaved head. Also, some fanzines from that era published articles about skins. However, Kaoz and G-3 have been foundational in the Peruvian hardcore and hardcore punk scenes and have always identified themselves in that manner from those days until the present.

So, before 1993 we can confirm that there were no crews, collectives, or bands openly defining themselves as skinheads. Starting from 1993, every time new Peruvian skinheads have joined our movement, it’s because they identify themselves as such – there’s a sense of community and belonging. This has led to the creation of collectives, bands, banners, skinzines, and the dissemination of music – and most importantly, openly expressing that we are skinheads.

What is the first Oi band formed by skins in Peru and what other groups followed?

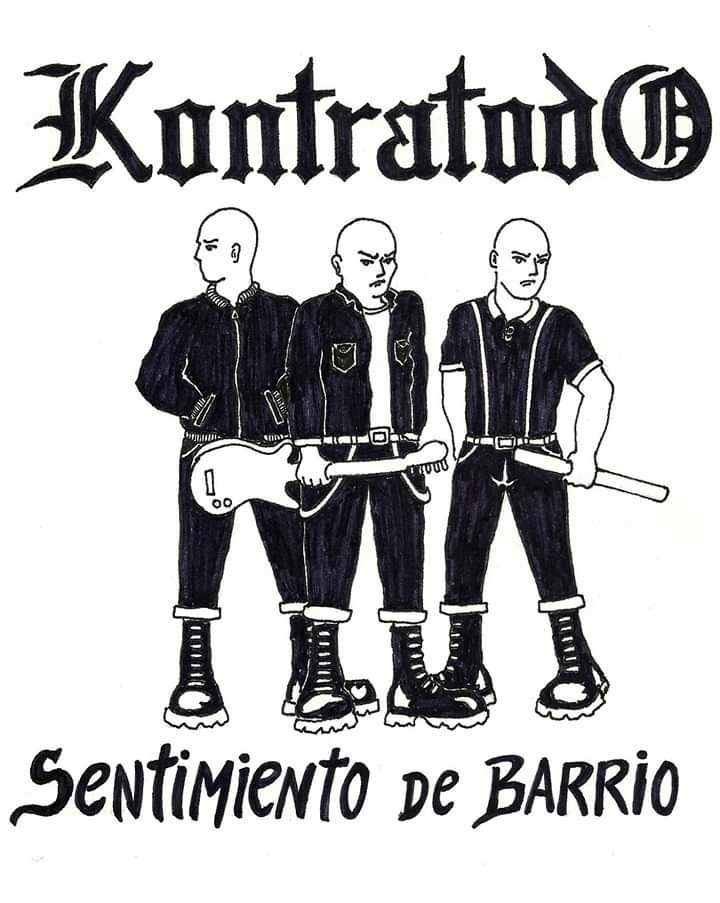

Kontratodo was the first skinhead band, formed in 1993 in the neighbourhood of Comas. They sang about the skinhead culture, class pride and their experiences in the neighbourhood. They were the children of Andean migrants who had moved to Lima, so their songs were often about the migrant experience and even incorporated some Quechua words [Quechua was the main language family of the Inca Empire – Editor].

In that initial era, a few other bands existed:

Tropa de Choque (Shock Troop), a band of anti-fascist skinheads from the Comas neighbourhood that played a hard and direct style of Oi. Their mission was to champion the core values of working class culture, and were active in 1998.

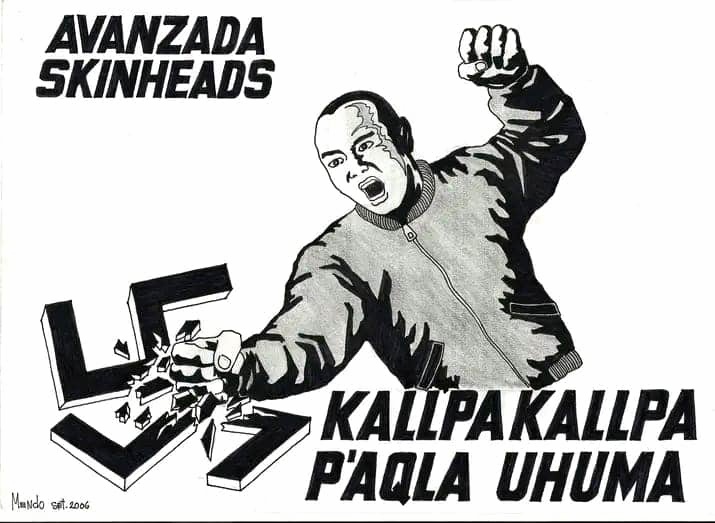

Kallpa Oi! was a skinhead band with members of the R.U.K (Resistencia Urbana Condevilla). They played a lighter style of Oi music infused with a neighbourhood vibe and anti-fascist stance. They were active between 2001 and 2002 (Kallpa means strength or energy in the native Quechua language).

In the second era, the band Estamento Combate (Combat Squad) came into being. They formed at the end of 2003 and remained active until 2004, recording a demo that was never published. One of their songs, ‘Palestina’, had a classic Oi sound and conveyed the bravery and resistance of the Palestinian people.

During the third era, the following bands emerged:

Autocrítica Oi! (Self-Criticism Oi!): This RASH-affiliated band from the Ate Vitarte district was formed in 2006 and remains active. Their music is imbued with libertarian ideas, and they’ve played a crucial role in fostering unity between the punk and skinhead subcultures. Two of their members are skinheads and are part of RASH Ate.

Sangre Dorada Oi! (Golden Blood Oi!) formed in 2013 and were active until 2017. This band adopted a classic Oi/punk rock style, with lyrics about everyday life and the vindication of the working class. They left a powerful and important album for the Oi scene of our country, titled First Round.

Bajo Presión (Under Pressure) are a band from La Victoria neighbourhood. Originally formed in 1992 with a hardcore tendency, they returned in 2013 with an anti-fascist skinhead stance. They play street punk/Oi with direct lyrics that denounce corrupt, fascist politicians and racial prejudice. Bajo Presión remains active.

Última Amenaza (Last Threat): This band was formed amidst tear gas and social protests at the beginning of this year. They play old school Oi/punk and their lyrics revolve around street life, neighbourhood experiences, working-class pride, and political and social discontent.

Finally, as for other bands aligned with this style, let’s mention Jhatary Oi! and Rojos de Rabia (Reds of Rage).

Tell me about the skinzines Cultura Skinhead and Resistencia Urbana. Who made them? Were there other skinzines?

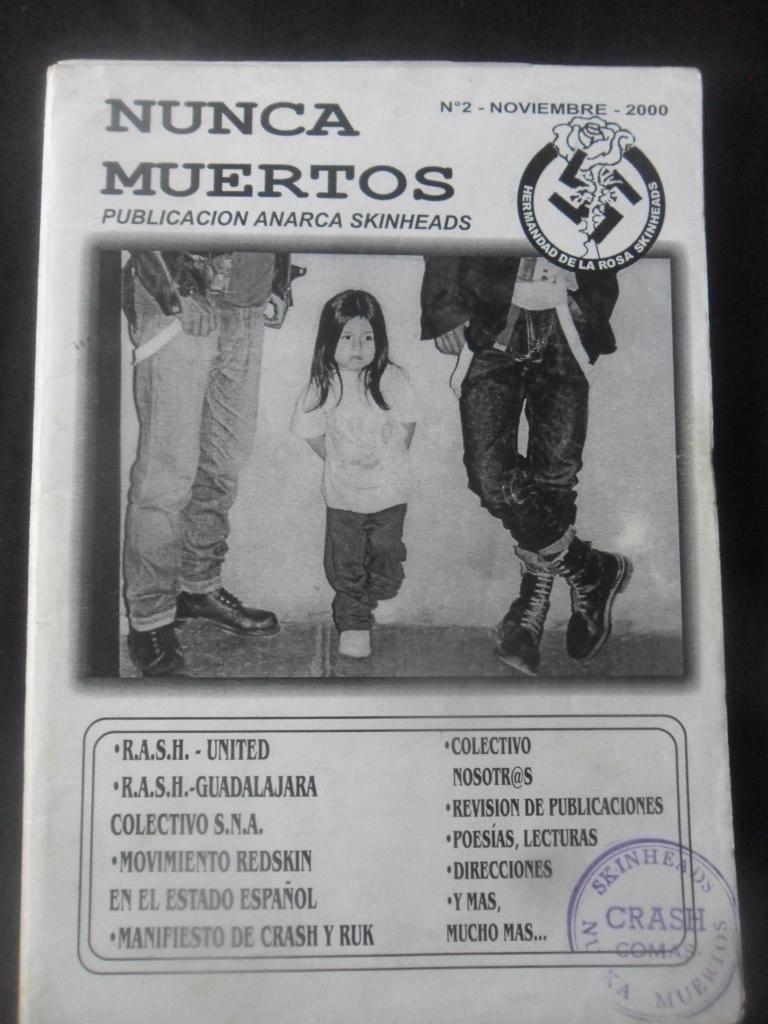

In the skinzines and publications from the first period, we tried to convey our ideas and inform about the true skinhead culture with a strong anti-fascist and anti-racist stance. All of this was before the arrival of the internet, so skinzines held considerable value for us.Regarding the skinzines you asked about, Cultura Skinhead (skinhead culture) was produced by Juan Malca, also known as ‘Burro’ (RIP), and Resistencia Urbana (Urban Resistance), created by David Vara, known as ‘Chato David’ (RIP). Some of the other skinzines and publications from that era, i.e. before 2000, included Cambio Radikal (the newsletter of C.R.A.S.H. Comas), Nunca Muertos (Never Dead), published by Mendo, Nosotros (the newsletter of Colectivo Nuestros), Arengas (a poetry newsletter), Kallpa newsletter, Desafía (Challenge), La Toma (a publication by Fuerza Marginal), Ácrata Invasion, and Reaxiona.

How does RASH (Red and Anarchist Skin Heads) fit into the history of the movement? Are they still active?

RASH played a role in our movement during two distinct periods. The first was in 1998, when information about RASH came through skinzines. Later, in 1999, some skinheads found themselves identifying with RASH’s principles and received an invitation from RASH Colombia to set up a branch of the International Confederation of RASH. This gave birth to RASH Peru. They remained active until 2002, with a strong focus on political activism. Their actions included fieldwork, sabotage of elections, graffiti, distributing leaflets, and participating in marches.

The second period was towards the end of 2006 in Ate Vitarte, a district with a strong working-class tradition. The skins from that neighbourhood decided to form RASH Ate, and since then, they have continued their steadfast march. This group played a pivotal role in reviving and strengthening the bond between punks and skins – in previous years, the relationship between these two subcultures had not always been harmonious. RASH Ate engages in various activities, including spreading their ideas through street interventions in their neighbourhood, participating in marches, and, most importantly, using music to convey their message through their musical arm, the band Autocrítica Oi!

An interesting detail is when Alex Ellui from the British Oi group Battle Zone moved to Peru in 1999 and formed BZ with members of Leuzemia and Histeria Kolektiva. What impact did that have and did you know his past involvement with the RAC scene and neo-nazi groups?

There are episodes in our history that cannot be denied, but that person had no major significance. In this interview, our purpose is to discuss the history of the skinhead movement in Peru, a history that has been shaped by all of us – the crews, collectives, and bands we’ve been talking about, as well as the individuals within our movement, particularly those who still embrace this way of life.

To answer briefly, since we don’t want to dwell on something of little relevance to us, when we first encountered that person, we had no knowledge of his background. Later on, when we learned about his involvement with RAC and neo-nazi groups, he assured us that it was a thing of the past. It’s worth noting that some of the younger members who initially joined BZ eventually started displaying right-wing tendencies and expressed sympathy for RAC, and we confronted them about it. Years down the line, some of these individuals became part of a neo-nazi group that had to be smashed and kicked out from the underground spaces.

[When editing the interview, I was curious to know who the Peruvian neo-nazis, who aren’t politically ‘white’ in the American or European sense, consider their ‘racial enemies’. Freddy Alva says: “There’s a long history of discrimination by people of mixed or Spanish background in Lima towards newly arrived indigenous immigrants from the mountains, so I presume that’s who they’re referring to or the Afro-Peruvian, Japanese/Chinese-Peruvian population – Editor]

Speaking of fascists that tried to infiltrate the scene, something that for the most part has been contained in Peru, are there any instances where you had to confront these elements?

Indeed, as you say, we’ve contained these elements. We’ve always had a firm stance regarding anyone, be they crews, bands, or individuals, attempting to taint our image with neo-nazi or right-wing ideologies: we’ve swiftly confronted them.

In the second era of the movement, there was a neo-nazi crew called Arma Blanca (White Weapon) that showed up at The Exploited concert in 2003. They were outside the venue, distributing propaganda. Out of all the groups present, only we confronted them. One of our members was from the early skin era, and among the neo-nazis, there was an individual known as El Gordo Memo, an old Subte Rock veteran. Unfortunately he had a gun, so there was no chance of a fair fight. Several years later, we found him again, and like a coward he refused to fight, asking for forgiveness for his past actions.

In 2017 we heard that some fence walker types and nazi lovers had formed a crew and were seen attending Subte Rock shows in the heart of Lima. Notably, one of these individuals had a band set to make their debut at a concert alongside various bands from our own circles. On that day, we entered the concert and disrupted the performance of the band in question. We directly confronted the guy. He was wearing a provocative t-shirt, which he promptly turned inside out when told to. Before the eyes of the crowd, we told him that if he and his mates didn’t clean up their scene, we would. This was a warning to the neo-nazis: we let them know this wasn’t a game.

In 2018, we went hunting for them. At one point, we managed to catch them all together as a group, and there was an intense confrontation on an avenue in the centre of Lima. These people typically carried weapons such as switchblades and chains. In the heat of the moment, we grabbed and used whatever we could – rocks, belts, and fists. They fled in disarray, beaten to a pulp and leaving their leader behind, who was crying and in poor condition. They never came back since then and the crew soon disintegrated. Whenever these groups appear it affects us because they appropriate our aesthetic and we have an obligation to act because we are coherent in our thoughts and actions. In the counterculture, there are tons of songs and slogans against fascism and calls for direct action, but that’s as far as it goes. We come from street culture, where without action and without being consistent you can’t earn respect.

How do you see the skinhead movement in Peru at the moment, and are events like the ‘Lima Oi!’ concerts still taking place?

The skinhead movement in Peru has remained vigilant and strong over the years. We’ve never been many, but enough for the movement to remain active. For example, at the end of 2022 and in early 2023 there were fierce social conflicts, a lot of repression and state-sanctioned murders. Since we’re skinheads from the working class, we have to be present during these struggles. Many skinheads have actively participated, marching and fighting alongside other collectives and labour unions, some of which they are also members of. We have also organised campaigns to collect funds for our brothers who travelled from other provinces to join the struggles.

The currently active bands are Autocritica Oi! and Bajo Presion. A new band is in the process of forming and is soon to make its debut. We are on Facebook as Cronicas Skinheads Peru – our page is a space dedicated to discussing various aspects of our movement and history.

There’s also ‘Reggae Salve A La Reina’, who have been hosting events since 2018, focusing on old Jamaican sounds from a punk perspective. They promote vinyl records and aim to expand the sound system culture in the country. Over the years, they’ve been active on the streets, showing support for anti-fascist skins in Lima.

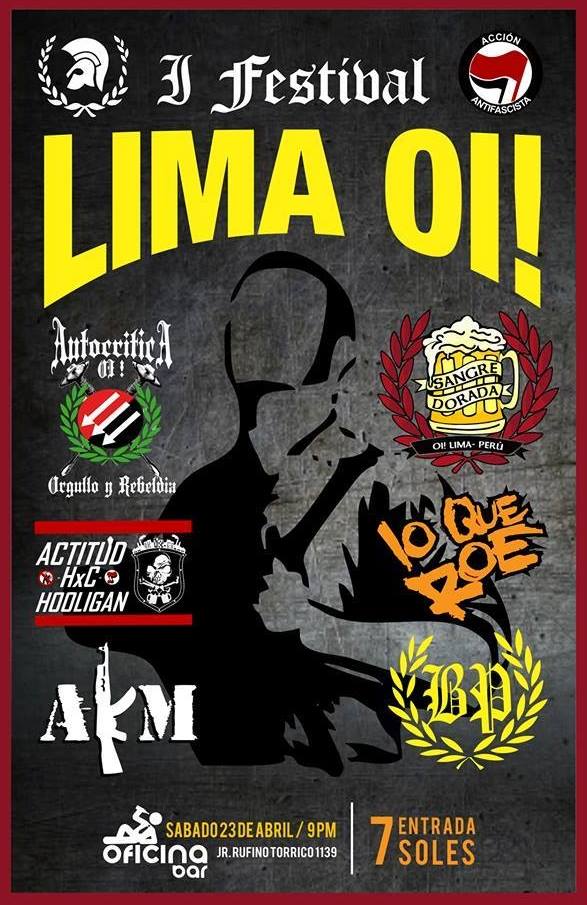

Since 2016, ‘Lima Oi!’ has provided an important space to promote concerts with anti-racist tendencies, be it Oi, street punk or hardcore. In December 2022, members of Autocritica Oi! and Bajo Presion returned to take part in what they had initially set in motion. They were joined by the band Los Navaja, and this concert was renamed ‘Lima Street Oi!’ with the addition of the band Los Navaja, this (concert) has been renamed ‘Lima Street Oi!’. From the beginning to now, there’s been an unbroken continuity in our movement. Those who were part of it at various points and those who have joined later have all contributed to the development of the skinhead movement in Peru.

How can people interested in the skinheads of Peru get in touch? Is there a blog or zine you recommend?

Currently, there are no active zines or blogs within the movement. You can find us at concerts where bands like Autocritica Oi! and Bajo Presion play. For anyone else in or outside of the country you can get in touch with us through the Cronicas Skinhead Peru page on Facebook. You can also get in touch with Autocritica Oi! and Bajo Presion through their social media as well as the ‘Reggae Salve A La Reiena’ sound system.

Thank you so much for the interview. Any last comments?

Thank you for your interest in our culture and for reaching out to us through our Facebook page, Freddy. We’re grateful for the opportunity to share our story in your zine. In closing, we want to stress that the skinhead way is a lifelong commitment. We will keep it based on the streets, in the neighbourhoods, and in the working class, with a firm anti-fascist attitude. We will prevent it from becoming a circus of timid and ambiguous people.

Freddy Alva 2023

Oi, mate! Just to let you know that over the years I have translated some of your articles into Bulgarian for my blog, especially in the last month. I hope you don’t mind. You can check them up. Cheers from Bulgaria!

https://radicalterraces.wordpress.com/

LikeLike

Fucking hell, that’s incredible – I think we’ve just found our Bulgarian soulmate. What town are you from?

LikeLike

Sofia.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article. Keep on keeping on.

LikeLike

really cool; cheers matE!, MAG

LikeLike

It Fills my heart with pride reading this.

Great article.

Keep on keeping on.

Roddy Moreno

LikeLike