I was tempted to let Papillon by Dalton enter our Classic Albums series, but it isn’t what you’d call a classic like Red Alert’s We’ve Got the Power or Voice of a Generation by Blitz just yet. For one, it only came out three years ago – and few people outside of Italy will have heard it.

For the Italian skinhead and ultras scene, though, the album was a game-changer and a towering achievement. Dalton, a Roman group formed by former members of Oi bands Pinta Facile and Duap, debuted in 2015 with Come stai?, an album with packed with melodic but robust bovver rock hits. As I have written here before, they’re “very Italian, musically too … their music is pub-rock and glam-rock based, but it has the atmosphere of Italian working-class bars. They sound authentically like where they’re from, mixed with what they’re into”.

I’m attached to Dalton for personal reasons too. In the run-up to my move from England to Italy in 2020, their music got me hyped-up for the big day. It was also around that time, in the midst of the pandemic, that Papillon came out on Hellnation, heralded by the YouTube release of ‘Qui Quo Qua’ – a tune that sounded like a romantic summer hit on Italian 70s radio rather than anything recognisably street punk. With Papillon, the band expanded into power pop, cantautorato (Italian singer-songwriter) and other styles whilst maintaining the vintage rock ‘n’ roll grit and down-to-earth prole edge. The peak of the album is ‘Sottoproletariato’, a reggae-punk anthem like they don’t make them anymore (but used to in the 70s–80s, when songs like The Ruts’ ‘Jah Wars’ or Daily Terror’s ‘Hinterlist’ were recorded).

In June 2020, the L’ordine nuovo website published a review of the album by Nicola Billai. I like this review so much that I’ve decided to translate it: Nicola has captured the spirit and essence of Dalton much better than I could – his text makes for a perfect introduction not just to Papillon, but also to Dalton in general.

Says Nicola today: “Papillon is already three years old and yet Papillon remains, for the genre and for the audience it’s aimed at, a vanguard album so far unsurpassed. The lyrics are radical and, dare I say it, essential. Dalton was the lightning bolt that struck through the clouds, integrating old sounds like blues, rock & roll and hints of roots reggae, which is quite atypical for the genre they emerged from. I don’t think there’s a band on the Italian scene that has gone this far”.

Nicola Billai is, in his own words: a carpenter, a fan of street music, a communist skinhead and a family man. Today he devotes himself to trail running and tending a centuries-old olive grove with his partner Laura and his children. Enjoy his review below or find the original Italian article here.

Matt Crombieboy

We, as is known, came into the world

steeped in shit and filth.

Merit, decorum and greatness

are all merchandise for the Lords.

To His Excellency, to His Majesty, to His Highness

incense, medals, titles and splendours;

and to us workmen and servants

the rod, the load and the halter.

Christ created the mansions and palaces

for the prince, the marquis and the knight,

and the ground for us fuck-faces.

And when he died on the cross, he had the thought

of shedding, in his goodness, amid so much torment

for them the blood and for the rest of us the serum.

It’s right there – Gioacchino Belli’s verses, delivered by Marco Giallini’s voice, would be enough to sum up and explain in brief what Papillon, the new album by the great Dalton, is about.[1]

Yet this would be reductive because it would fall short of capturing the allure of the street dandy, of the sub-proletarian, of Oliver Twist rising from the table and asking for another bowl of soup – the kind of allure that Dalton have always conveyed to us.

We’ve heard many such stories before. We’ve read them in Valerio Marchi’s books, specifically in Teppa: storia del conflitto giovanile dal rinascimento ai giorni nostril [Hooliganism: a history of youth conflict from the Renaissance to the present day].[2] We have lived and seen them with our own eyes.

They are stories about ‘kids like us’ emerging from the dark alleys of cities and towns, dressed up and ready for an ace night out. Dalton have recorded the soundtrack for this film composed of faded images.

At this point, you’d expect to hear the crackle of Oi vinyl coming from the speakers because Dalton’s attitude and lyrics, their stories and their lives are those of skinheads from the Italian capital.

But no. Instead we hear rock & roll as ordained by the Lord, dense with blues to the nth degree, tight and addictive, with the flavour of a rock band that knows how to handle keyboards, harmonica and sax. Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry are part of the group’s DNA. In short, they dig deep into the 1950s and 60s. Featuring guest appearances by those with whom they’ve shared stages many times (Gli Ultimi, Shots in the Dark, Lenders), Dalton have come up with a sensational record.

The album offers a snapshot of society that no one wants to see or hear because it’s too uncomfortable. No one, neither on the right or the left, wants to deal with the outcasts of society, the underclass, people who live from hand to mouth. But these people exist. They stand in the wings of the theatre, ready to walk on with their best clothes and their hat on, take a bow and tell the audience to go to hell.

Having established what this album represents from a ‘political’ point of view, despite being the product of a group that has never been politically-minded, it’s worth noting the painstaking care given to the lyrics, which are never banal or predictable.

Sometimes they sound like the kind of stories you hear outside a bar in the middle of the night, in the rain, told by some bloke you’ve met by accident (or maybe not), who insists on finishing his story even though you’re soaking wet. Or else, they sound like the tale of a worker winding his way through death, beauty and dreams… the usual dream, always cut short by the alarm clock commanding him to get up and go to work.

There’s not one track that is completely unconnected to the others, nor even to the songs from Dalton’s other albums. The parallels between ‘La classe operaia resta all’inferno’ [The working class remains in hell, from Dalton’s debut album] [3] and ‘Sottoproletariato’ [Underclass] are a striking example: no solutions are offered; there’s no revolution or revenge around the corner; no rabble-rousing or call to revolt – because there’s no antidote to poverty and despair.

Since there are no solutions for the underclass, or none to be seen, we’ll just have to remain sat on the same old steps, smoke a cigarette and raise our glasses to the next shitty day. The record isn’t the innovation of the century, which incidentally isn’t something we even wanted. I could almost play it between those that my dad used to listen to on his portable record player without noticing any great difference in style.

It sits well among my Oi records, though, because that’s what it is: an Oi record about Oi people, but played with all the character and love of detail that Oi music lacks. Apart from this, all that’s left to say is: go and hear them live.

PS: A key external element is the 7-inch single ‘Ci siamo persi’ by Dalton [an Italian-language cover of Elvis Presley’s ‘Suspicious Minds’ – Editor]. Without that one, the Papillon album is missing a song. These guys are outstanding.

Nicola Billai

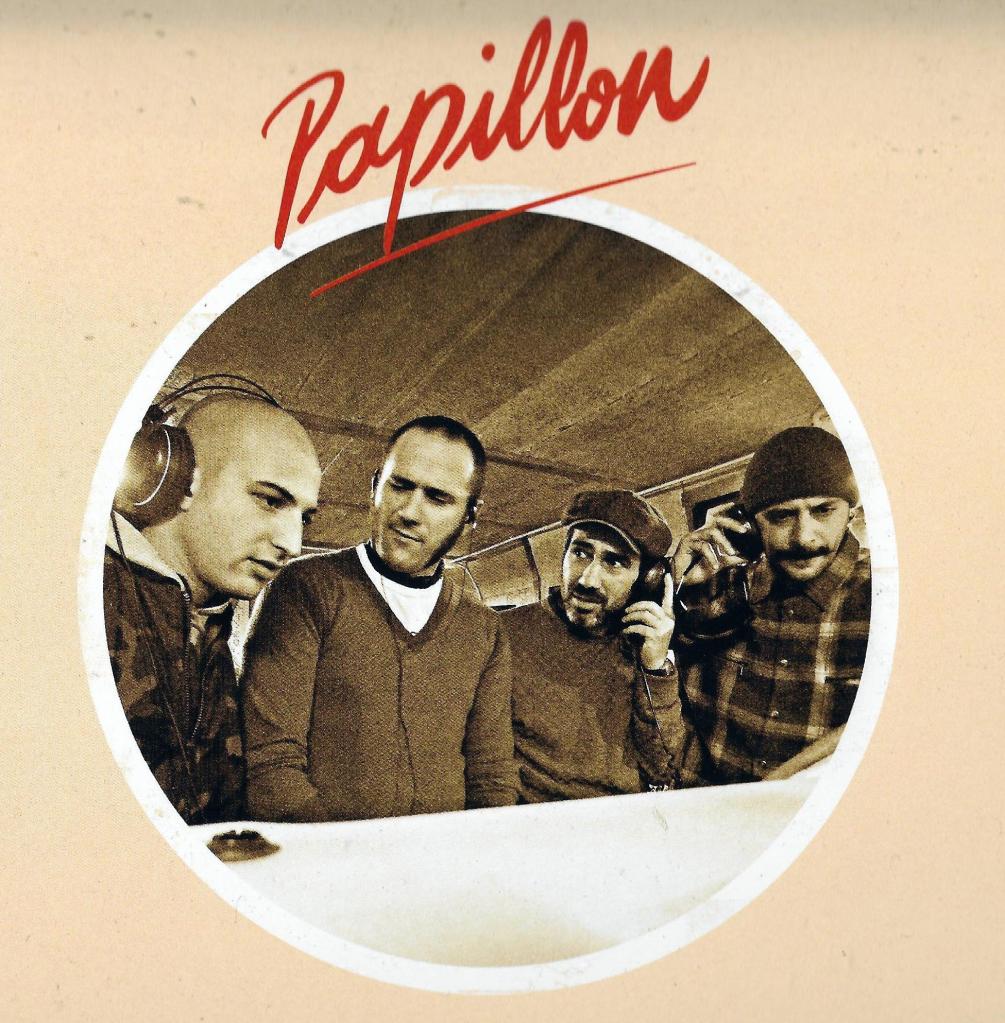

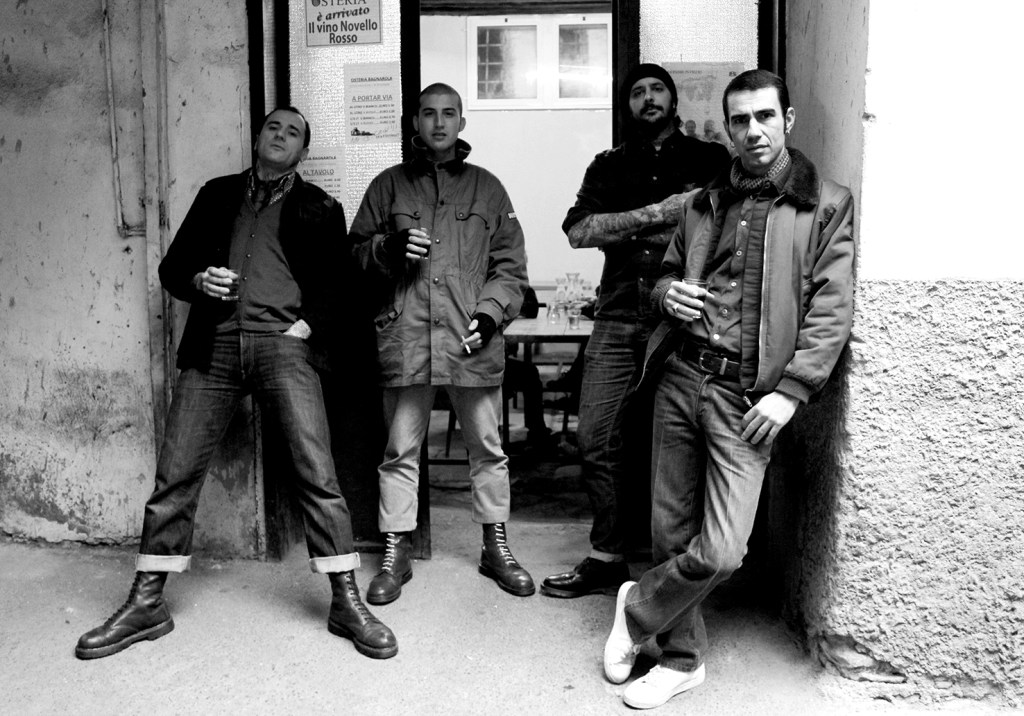

Main photo top of page: Federica ‘La Rude’ Scaricamazza (ZanzaRude)

[1] Giuseppe Gioachino Belli was a 19th century Italian poet famous for his often satirical and anti-clerical sonnets in Romanesco, the dialect of Rome. The poem spoken by Marco Giallini that opens Dalton’s album is ‘Li du’ ggener’umani’ (The Two Types of Humans, 1834), translation ours.

Marco Giallini is a Roman actor known for his part in the Italian-French co-production ACAB – All Cops Are Bastards (2012), among other roles. The band think of him as “a friend and someone from our circles” – Editor ↵

[2] Valerio Marchi (1955–2006), sociologist and founder of the Libreria Internazionale di San Lorenzo [International Bookshop of San Lorenzo]. His books were often devoted to subcultures such as skinheads and ultras. Marchi became a kind of spokesperson for the Italian skinhead movement. He was a political militant and anti-fascist, Roma fan and punk, reggae and ska expert – Editor ↵

[3] The title is an allusion to The Working Class Goes to Heaven, a 1971 Italian movie about a factory workers’ realisation of his position in the world. The film well worth watching, and not just for Mariangela Melato’s feather cut – Editor ↵

Wow. Listening to „Papillon“ nonstop since yesterday, when I read this article here. Thanks! Thanks! Thanks!

LikeLike