Investigating the history of Poland’s skinhead scene is tricky. Even if the mid-80s beginnings were relatively apolitical (see our article on Kortatu’s visit to Warsaw in 1987), no clear demarcation between ‘boneheads’ and other factions emerged until at least 1992. Although the information flow from Western Europe to the Polish People’s Republic was somewhat hampered in the 80s, whatever made it through the Iron Curtain in the form of zines and tapes was happily absorbed. This eclectic mix included the likes of Blitz, Kortatu, Symarip and Angelic Upstarts, all of which earned mentions in the pioneering Polish skinzine, Fajna Gazeta – but also Skrewdriver, provocative nazi posturing and ultra-violence against enemy tribes. All of these influences added up to a subculture made up of hooligan ex-punks, determined to make a name for themselves as the most fearsome youth cult of all.

In Wroclaw, located in Lower Silesia and formerly known as Breslau during its time as part of the German Reich until 1945, the emergence of skinheads dates back to approximately 1986. They regularly congregated in the Rynek (market square), situated in the historic city centre. Back then, this area had a rougher reputation, quite different from the gentrified tourist destination it is today. Among the prominent figures within this tribe were characters who went by nicknames such as Bonanza, Smolar, Czeski, Kufel, Mareczek, Siudy, and Robson. As the skinhead scene took on a more political stance during Poland’s transition to capitalism, Robson, then 19 years old, became a prime mover. He helped establish the Aryan Survival Front (AFP), a bonehead network modelled after Britain’s Blood & Honour. Robson also took on the role of manager for an emerging RAC band from Wroclaw that would soon become influential: Konkwista 88. Reflecting on this era in a brief interview with the Gazeta Wyborcza newspaper in 2005, Robson noted that he had been “the most ideologically driven among them”. After all, it was him who “came up with the idea of forming the AFP (…), helped to set up Konkwista 88, organised their first gigs, answered all their letters, as well as contributed the odd verse or chorus to their songs”.

On 24 February 1990, Robson and some 15 mates disrupted a street demonstration in Świdnicka Street, shouting abuse at African students and Solidarność activists who were celebrating Nelson Mandela’s release from prison. The ensuing scuffle made headlines as the first racially motivated riot in post-socialist Poland. Mieczysław Michalak’s iconic photograph of the action – featured at the top of this page – went around the world. Video footage of the incident can be seen in the TV documentary Krzyczylismy Apartheid (2006), available on YouTube with English subtitles.

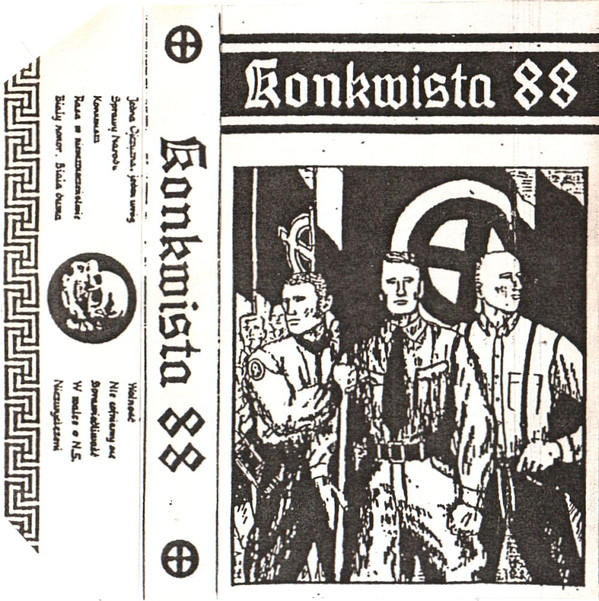

Legend has it that Konkwista 88 was formed that same evening. In any case, some of those involved in the scuffle became part of the band. They originally wanted to name the band after Konkwista (Conqueror), a political thriller by Waldemar Łysiak that had come out in 1988. That night, Robson, appointed as the band’s manager, suggested adding the number ’88’ to their name – though not necessarily as a reference to the year the book was released… A series of tapes soon emerged, showcasing competent songwriting and solid musicianship paired with overtly National-Socialist lyrics. These recordings established Konkwista 88 as one of Poland’s two leading neo-Nazi RAC acts in the 1990s, alongside Honor from Gliwice.

For many protagonists of Wroclaw’s nazi skinhead scene, things ended badly. By the end of the decade, several were undergoing alcohol or drug therapy -like Konkwista 88’s guitarist, Czerwony, who spent much of the 90s shooting up heroin outside Wrocław’s central train station. Others graduated to organised crime, such as Mareczek, who was eventually shot dead in an underworld feud.

Not so Robson: in 1993, after a period of doubt, he switched sides and became a redskin. In 1996, Łukasz Medeksza conducted a comprehensive interview with him, originally published in the Polish punk zine Pasażer and the anti-fascist magazine Nigdy Więcej. An interesting historical document, the interview offers insights into Wroclaw’s nascent skinhead scene and its rapid drift towards the extreme right after 1989. We have translated the interview for your convenience and have also asked retrospective questions to the original interviewer, Łukasz Medeksza.

We also approached Robson for an interview, and while he responded politely, he declined the request without citing any specific reasons. We can therefore only provide a rought outline of the events that unfolded in his life after 1996. Robson remained a redskin for at least another decade – in the 2006 TV documentary referenced earlier, he was still seen sporting crop and a button-down shirt. During this period, he organsied security for leftist events, which ultimately led him to become a member of the Polish Socialist Party (PPS), a left-wing organisation focused on working-class politics and national sovereignty, inspired by the historical PPS founded in 1892. “I can’t remember if I was the party chair for Wroclaw or for the whole Lower Silesian voivodeship”, Robson said in Gazeta Wyborcza, “but I was definitely on the national council”. Later, he set up a security firm that supplied bouncers for Wroclaw’s gay and lesbian nightclubs., and today he appears to be a family man with a keen interest in boxing.

Alas, Robson’s decision to decline our interview request leaves a number of questions unanswered. We understand that Robson embraced neo-nazism, which is distinct from original nazism in that it doesn’t endorse pan-Germanism, Prussianism or Nordic supremacy, but promotes the international solidarity of the whole so-called ‘white race’. The latter is an Anglo-American concept introduced into the movement by George Lincoln Rockwell, who merged aspects of Hitler’s ideology with the segregationist racism of the southern US, thereby creating the ‘white nationalist’, Klan-loving neo-nazism that we know today.1 This serious modification allows Slavic peoples such as Poles and Russians, once designated for enslavement and extermination as part of Hitler’s colonisation project, to join the ‘white race’ and wave swastika flags…

Even so, it isn’t always easy to keep historical nazism and its Americanised update apart. As per Robson’s own admission, the imagery served up by Konkwista 88 was “strictly Hitlerite”. The band even produced a song that praised the virtues of the Waffen-SS and lauded its Eastern campaign. It’s a glaring contradiction that is difficult to understand: how can a Pole – even a fascist Pole – glorify an organisation whose actions and overall mission were so deeply contemptuous of Polish life?2

Morover, if Robson had no time for the narrow nationalism present in parts of the scene, why didn’t he gravitate towards, say, the pan-Slavic sentiments embraced by some other factions?3 And if he was mainly into the ‘leftist’ aspects of nazism, as he relates in the interview, why didn’t he instead opt for a path akin to the band Sztorm 68, who rejected nazism and ardently pursued a ‘national-bolshevik’ direction?

Chances are we’ll never know. Nor will we learn what Robson makes of his interview with 25 years of hindsight. Given Wroclaw’s complicated history – the city has been variously German and Polish – it would have also been interesting to learn more about the strange identity crisis that apparently tormented some of his friends. Despite coming from a city largely populated by descendants of eastern Poles resettled from Lwów/Lviv in 1946–47, it appears that a significant number of Wroclaw skinheads experienced a phase during which they identified as German….

A note of caution: although the translated interview is the authentic voice of someone who was part of Wroclaw’s early skinhead and bonehead scenes, it shouldn’t be treated as the “last word” on that era. For all the fascinating and detailed historical information, it represents only one individual’s subjective perspective and, as such, is inevitably partial.

We’ve made only minor edits to the interview, omitting some details about lesser-known figures from 1990s Poland that we deemed irrelevant from today’s perspective. Additionally, we’ve removed some “revelations” about Nicky Crane that were partly old hat and partly inaccurate. Just in case this needs saying: we’re running this article as part of our investigation into the historical beginnings of the Polish skinhead scene. We do not endorse racism or nazism, and we think that Robson’s decision to become a redskin – especially in what was once known as Poland’s “bonehead capital” – commands recognition and respect.

We’d like to thank Łukasz Medeksza for replying to our questions. Many thanks also to Mieczysław Michalak, who allowed us to use his photograph of the February 1990 riot at the Nelson Mandela demonstration. Michalak has been a photojournalist for over 30 years – some of his work can be seen on his website here.

Matt Crombieboy

- “My task is to turn this ideology into a world movement”, Rockwell said of his utalitarian approach in an interview with Playboy in 1966, “and I’ll never be able to accomplish that by preaching pure Aryanism as Hitler did. In the long run, I intend to win over (…) the people of every white Christian country in the world.” ↵

- See also the nazi government’s Master Plan for the East: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generalplan_Ost ↵

- The political Polish skinheads of the early 90s split into three factions: 1) ethno-nationalists who drew on the National-Democratic movement (1886-1947) and endorsed Catholicism as part of Polish identity, 2) neo-nazis who considered themselves part of an international movement comprising the entire ‘white’ world, 3) the ‘Slavic’ faction, which drew on eclectic sources and comprised all manner of revolutionary nationalists, pan-Slavists, neopagans, neo-fascists and even a few ‘national communists’. The common denominator was their desire to flesh out a radical nationalism that was not linked to nazism or Catholicism. ↵