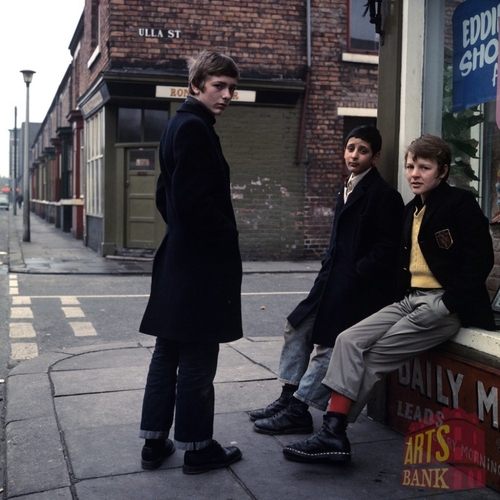

‘Ulla Street Boys’ by Robin Dale was conceived as part of an ethnographic study of a post-industrial Teesside already in decline by the early 1970s. Sometimes referred to alongside his ‘A Spot of Bother’ taken during a match at Middlesbrough’s Ayresome Park ground, it has since come to define a profoundly regional take on suedehead. The boys, found on a terraced street corner in central Middlesbrough (the street still largely exists, save for the odd demolished part here and there), examine the camera as intently as it surveys them. An all too rare perhaps depiction of skinheadism in one of its more multiethnic settings, Andrew Stevens spoke to the Billingham-based photographer.

What was your background as a photographer before you took the picture?

Like many people in the area [Teesside], I was a tradesman at ICI, where I worked as a [lathe] turner. This was far from my love of photography as a teenager, but the steady income from ICI kept me in rolls of film and cameras. That enabled me to follow my love of photography as a hobby in my spare time, more or less.

How did you happen to chance on the three boys in the Ulla Street picture? Did you go out looking for such subjects that day?

Not really, it was for a five-year project on Middlesbrough as such [The Banks of the Tees], the buildings and industry. But I also thought you really needed to capture the people as well, the workers and their social life. It was a one-off, in effect, it just seemed to capture the moment and by that I mean I just pointed the camera. As with most of these things, by the time they’d realised I’d already moved on and left. If anything it’s ‘A Spot of Bother’ which seems to be more popular, though that was probably the first and last time I ever attended a football match. They just seemed to be there and caught my eye.

Did you have any subsequent contact with the boys since the photo was taken?

No, I’m afraid not.

How familiar were you with skinheads or suedeheads in Middlesbrough at that time?

Not at all, I’d never seen any before or since. That said, that’s the people, there was plenty of graffiti around the area to alert you to their presence, ‘Boots’ and the like. But they were invisible to me.

Why did you set out to photograph them then?

As I say, it was for my five-year project and I was working with a folk musician, Graeme Miles. With my first proper camera, I’d got a slide projector and we’d accompany the photos with music which Graeme had written about the area, whereas before that I’d used BBC library music and the like. The combination proved to be gold, as his music really seemed to get under the skin of the area and he used reel to reel tapes to splice recordings which matched the pictures.

Was there any reaction to the photo at the time?

Only as part of the social study really.

It wasn’t intended to coincide with ‘A Spot of Bother’?

I’d say it was entirely coincidental, they were taken a year or so apart and formed part of that sequence.

How aware are you of the significance of the photo today? As in on social media and the like.

I’m not aware at all, but if it has travelled then that’s great. I’m only really aware of the Japanese as adopters of British subcultures. My own era was rock and roll, the Teds, but as with everything you grow out of it, though I have fond memories of that era so I suppose I could relate to what the boys were experiencing. I also took some pictures of girls during the punk era, with green hair and PVC clothes, as part of a coastal study. It was ‘UK Subs’ written on her back which caught my eye, just something random really.

Many thanks to Robin for the interview and for letting us use his pictures. More of his work can be seen at the Mary Evans Picture Library.