Rip Off from Bologna are mainly known for one fateful event today: their performance at the Certaldo Oi festival in 1983, which became notorious as the ‘Italian Southall’. Vocalist Rozzi delivered a speech threatening to “hang the punks and the communists”, while two members of Rip Off’s crew stood on stage giving fascist salutes. All hell broke loose in the crowd. The whole night turned into one continuous mass brawl, and in the aftermath, Oi bands in Italy struggled to get gigs for years.

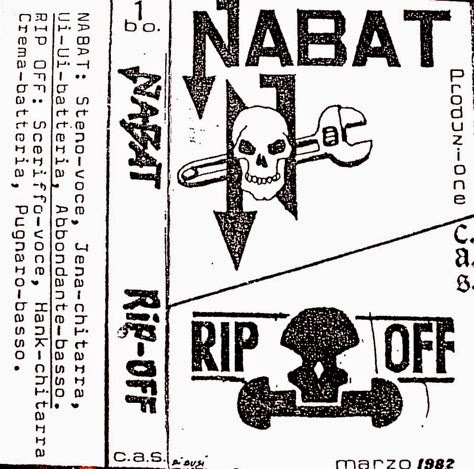

Less known is the fact that this disaster marked the first – and final – stages of an entirely new Rip Off line-up. Before that, a different formation, with Sceriffo on vocals and Crema (later of Wretched) on drums, had been playing under that name for three years. It was this original Rip Off line-up, which had no right-wing leanings, that recorded a legendary split tape with Nabat in 1982. Hellnation Records recently reissued these recordings on vinyl.

We met with the original vocalist Sceriffo at the Jolly Bar in Bologna’s Cirenaica quarter to discuss the band’s early history. Given the setting and the steady flow of alcohol, readers may forgive us for not always staying strictly on topic…

Matt Crombieboy

Matt: Hi, Sceriffo. What part of Bologna are you from?

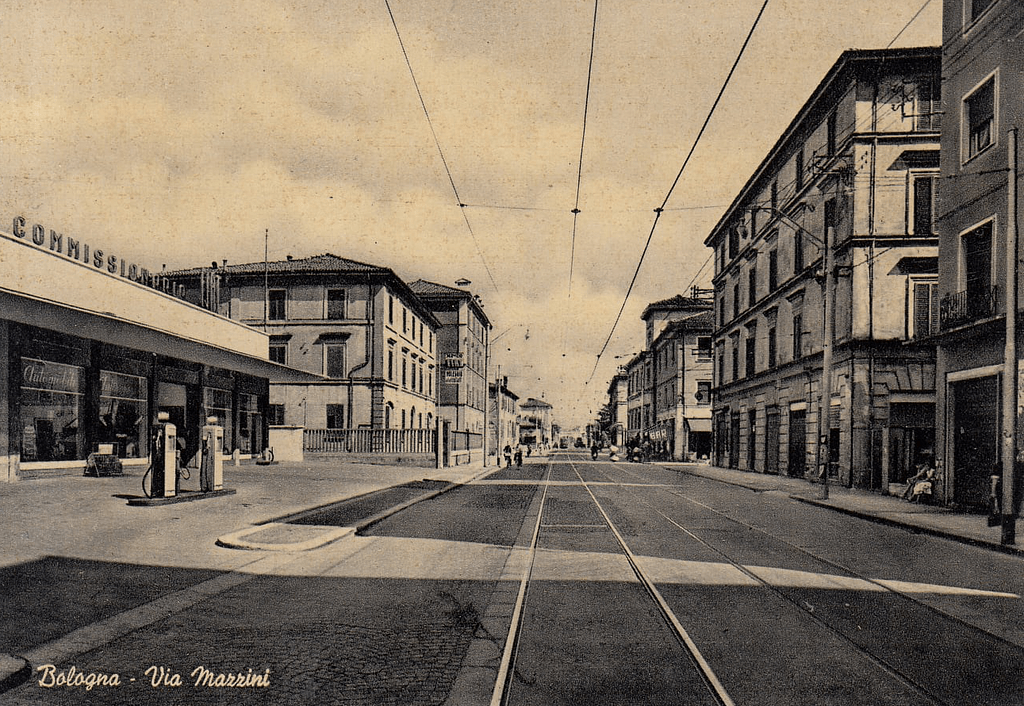

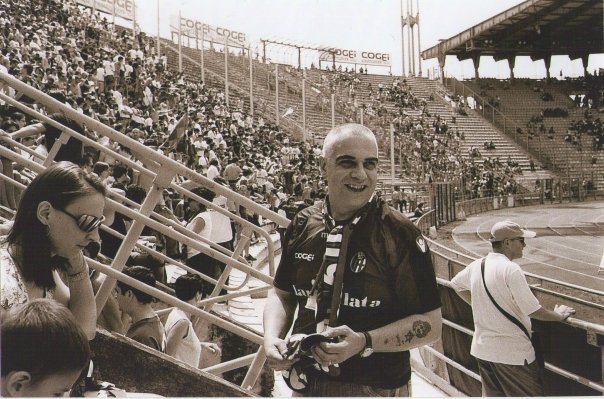

Sceriffo: I’m from the Mazzini quarter in southeast Bologna. That’s where I was born, and I lived there until about 20 years ago. Now I live on the west side, near the Bologna FC football stadium – more or less where the Barca quarter begins.

What was Mazzini like when you were growing up?

It had a bit of both – working class and middle class. Public services were good; there were schools and hangouts for youths. But like everywhere in Bologna at the time, there was a serious heroin problem. We’re talking the 1970s. Some kids at my school were using it, and a few people I knew from the stadium are now dead.

School? They must have been really young.

Oh yeah. I remember one kid from my school died of an overdose at 15. The fashion of the time was fricchetoni [post-hippie freaks], and heroin was everywhere.

So we can cut straight to the Rip Off song ‘Droge arma del potere’ [Drugs, a weapon of power] from your split tape with Nabat. In my opinion, it’s your best tune. Can you tell us something about it?

The song had a very broad meaning. Drugs make you lose control of your life, and someone who’s on drugs is much easier for the system to deal with. When you’re high all the time you don’t feel like hitting the streets to express your dissent. Drugs pacify you, and eventually, they end up killing off some of the most troublesome and desperate people. That also happened to quite a few early football ultras. It was a way of dampening the spirits of the most tenacious.

You never dabbled?

I only tried glue when I visited England – the poor man’s drug. Of course, it’s nothing compared to heroin, but I quickly realised how drugs can mess you up.

But are you saying in the song that drugs objectively benefit the powerful, or are you suggesting there’s deliberate intent behind it?

If you look at America right now, it seems that drugs are enabling a kind of natural selection. The weakest and most psychologically vulnerable – those living on the streets – are effectively being wiped out, especially with the rise of fentanyl.

Is that the absolute zombie stuff?

Yeah. And the American government stays completely hands-off. It was also a bit like that with AIDS back in the 80s, which mainly killed gay people, pleasure seekers, and so on.

Also, look at the rise of the black power movement in the US in the late 60s. The Black Panthers, for example, were very effective organisers in their communities. Then, suddenly, heroin flooded the ghettos on a massive scale – as if someone wanted it there.

Oh yes, of course – drugs pacify people and make them controllable. When you’re withdrawing you’d even sell your best friend to get drugs, so you’re easy to break. You’re no threat to the powerful at all. In Mazzini these things were quite widespread, and let’s not kid ourselves, they’re present in the Bolognina quarter and here in Cirenaica too.

Any movement that poses the slightest nuisance to the authorities is soon infested with drugs. Take the squatter and punk scenes of the early 80s. Or the ‘new left’ counterculture of the late 60s, which provided some of the raw material for the junkie scene of the 70s.

Exactly. Truth be told, for us, it wasn’t so much about whether a revolution was a real possibility. But at least we were focused on revolutionising consciousness. Today’s generation really has nothing at all – no values, no consciousness. You see that with the arrival of trap, into which even some of my contemporaries have thrown themselves. The only point seems to be getting high and having fun. We were the ‘no future’ generation, but I don’t think this one has much of a future either…

From today’s point of view, I find it hard to understand why people back then thought they had ‘no future’. You had a welfare state, strong trade unions, workers’ rights… today, none of that is left.

We saw ourselves as the ‘no future’ generation because, even though there was some freedom, it was a controlled freedom. As long as you had money and behaved yourself, you were fine – but step out of line and things would end badly for you. We were controlled by the Americans, who were our Russians, so to speak. In the East, you had dictatorships, but in Italy, we had the Christian Democrats in power, with an ideology that was backward, to put it mildly. They’d talk about liberty, but at the same time, they imposed religion on you. Politics and the church were completely intertwined, and Italians were a deeply repressed people. As soon as they went abroad, they’d queue outside brothels, something they’d never do back home. On top of all that, there was the constant nuclear threat and endless anti-Russian propaganda. But in the end, the Americans weren’t interested in bringing liberty to Russia; they just wanted to create new markets and expand their power.

The existence of the Soviet Union was actually beneficial for the working class in the West. It’s what forced the bosses to make concessions to the unions and pushed wages up. They were afraid that if they didn’t grant a welfare state and so on, they could lose everything. Now, without that threat hanging over them, they do as they please.

I’ll tell you what. A few years ago, I was earning 1600 euros; now I’m earning 1200. We’ve lost everything that was gained through union struggles. The unions are now in cahoots with the bosses. Gone are the days when we all agreed that the enemy was fascism or Berlusconi. The trade unions and those in government, who should have been on the workers’ side, have done nothing but crush us even more than a right-wing government ever would have.

Anyway, let’s talk about you and your band a bit as well (laughter). I’m guessing you became a punk sometime in the late 70s… how did that come about?

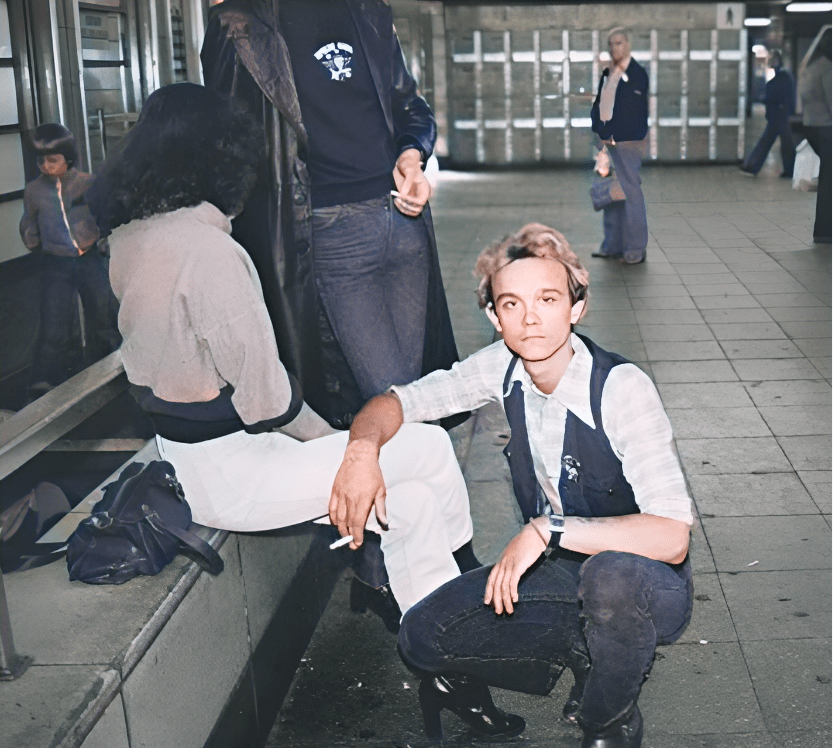

Yes, about ‘78/’79. Here in Bologna there was a big anti-establishment movement in ‘77. The universities were occupied, and there were even deaths. A movement exploded there that brought together all those who, in a nutshell, wanted to stay outside the system. There were free radio stations, but then private ones started popping up, playing ‘regime music’. The same was happening on the RAI network, which would play all this national folk music… you don’t even want to know! I used to get cassettes sent to me by friends in Germany. Sure, there was some stuff I liked, like Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple, but it was still niche music. People also listened to glam rock, like the Bay City Rollers. But in Italy, if they saw guys dressed like that, they’d immediately call them gay. I liked that alternative style, though. Then, in 1979, I went to London with my parents, and there I saw first-hand the change that was happening.

What was the first punk band you heard?

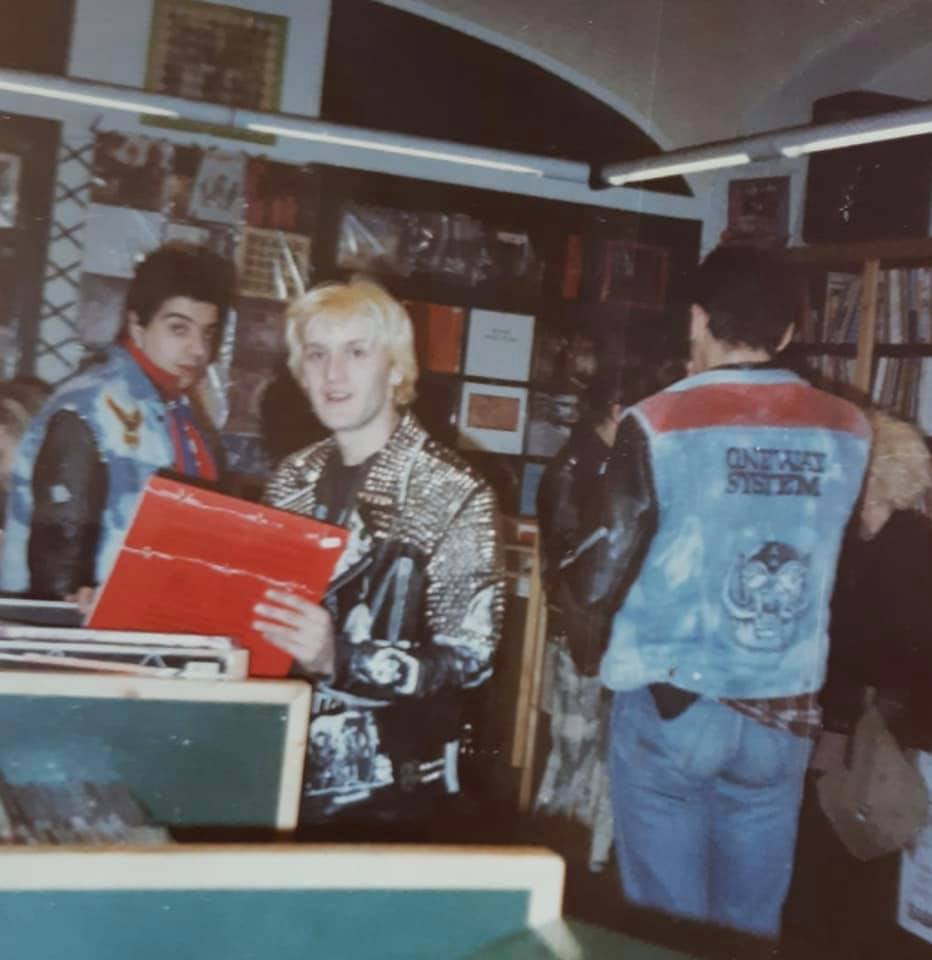

The first one I saw live was the Ramones in nearby Reggio Emilia – killer! [Reggio Emilia: a city about 45 miles from Bologna, hometown of legendary post-punk band CCCP Fedeli Alla Linea – Editor]. The first records I heard were the Sex Pistols and The Clash. From there, I started getting more interested. As soon as I saw someone wearing a leather jacket, I’d start a conversation right away. Small groups of people with the same musical passion were just beginning to form.

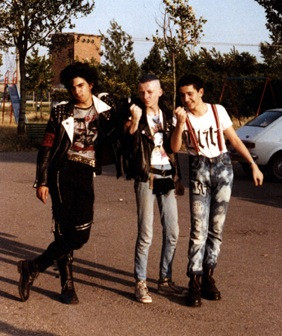

Were punks all united in 1979, or did factions already exist?

Factions formed as soon as there was even the slightest hint of a gathering. I remember New Year’s Eve in 1980; there was a party organised by RAF Punk [an anarcho-punk band and collective from Bologna – Editor] at the Cassero on Via Santo Stefano. There were about twenty of us, all united. That’s where the idea to form new bands started. I remember my first band was called Marones. The name was obviously inspired by the Ramones, but in Bologna, maroni means testicles, also known as coglioni, which can also mean idiots or arseholes… Another band of mine was named Gutalax, which is a laxative – so we were literally crap.

Back then, it was hard even to find a rehearsal room. We practiced on Via Pezzana in San Donato, in a storage space for a motorcycle factory. Although we tried to soundproof it, it was still incredibly loud. We spent our first two years with Rip Off in that spot. Then, our friend had to sell the place, so we moved.

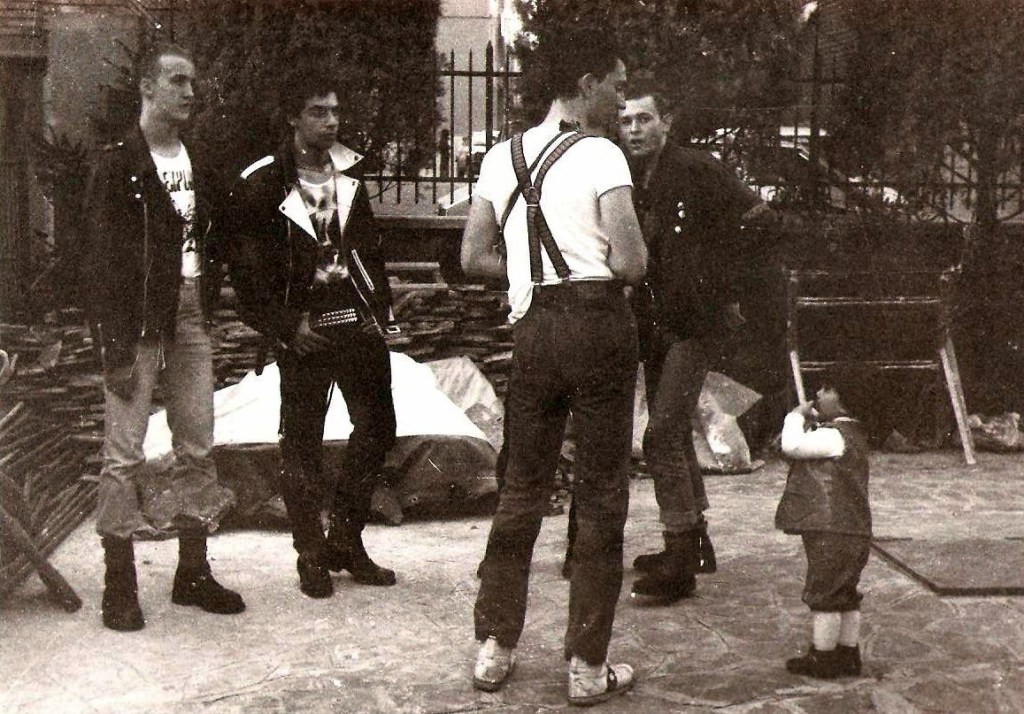

The Bologna punk scene soon split between the Crass-inspired anarcho-pacifists and the ‘nihilists’.[1] I imagine you were part of the latter faction?

Yeah. Look, at the time, we didn’t care about war. But looking back, I can see they weren’t entirely wrong – it’s just that they went about it the wrong way. Take the Clash concert in Piazza Maggiore, for example [a free gig organised in 1980 by the local administration, but disrupted by the local anarcho-punks — Editor]. They were right to say that working with the local administration of Bologna, which had always repressed us, wasn’t a great idea. But why ruin the concert? There were better ways to make a point. And seriously, when would anyone get another chance to see the Clash for free in Piazza Maggiore? That’s when the divide really started, and a wall went up between us and them.

Apart from that story, what was the main problem between you lot and the anarcho-pacifists?

It was their whole approach to life. On the streets, you’d often get crap from certain people, so you always had to be ready to defend yourself. We dealt with it by throwing punches and taking hits, but they’d just run away. They called us “Birra, figa e scarponi” [beer, pussy, and boots], while we called them ‘pastors’ because they were sanctimonious and always preaching to us.

Was there a class difference between you and them?

Well, yes. Have you ever heard of Helena Velena, their ideologue?[2] She’s the offspring of the general manager of Carpigiani, a company that makes machines for producing artisanal ice cream – famous all over the world. But I can’t say they all came from such privileged backgrounds.

There’s a Rip Off interview from an old fanzine, reprinted inside the album that’s just been released by Hellnation. You said something along the lines of hating anarcho-pacifist punks because “they go to London several times a year and buy everything they can. We don’t give a shit about London”. This would suggest they had more money to throw around, wouldn’t it?

Well, let’s say they were doing alright. I had to start working young and get by on my won because my parents didn’t give me any money. To us, they were the ‘communists with a Rolex’. There were definitely differences, but when they needed help, we were the ones they turned to.

Back to Rip Off. When exactly did the band form?

I’d say around mid-1980. At first, I played guitar, and Dedu (Gabri) was on vocals. We also had Tucano in the band, though we ended up kicking him out later.

I wonder what the first line-up sounded like. I’m familiar with your split tape with Nabat and the second tape with the second line-up. Did you have that raw Oi sound from the beginning?

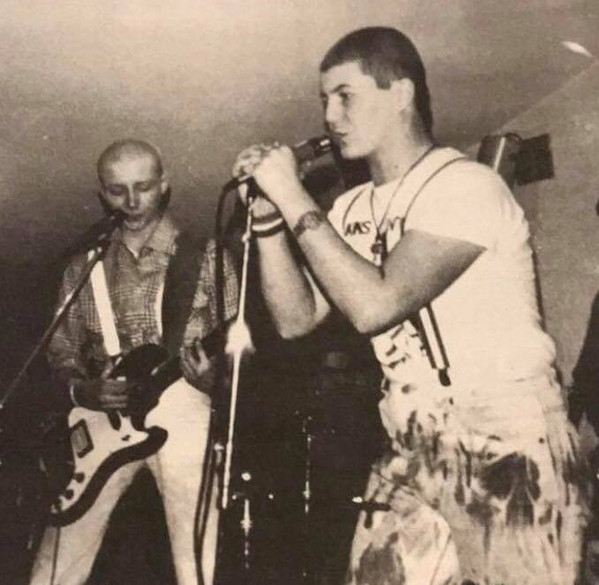

Not at first – it was quite different. We were still experimenting. I barely played the guitar, so I quickly brought in a guitarist and switched to vocals. With the first line-up, we only played two gigs. With the second, where I handled vocals, we managed about twelve—not a lot.

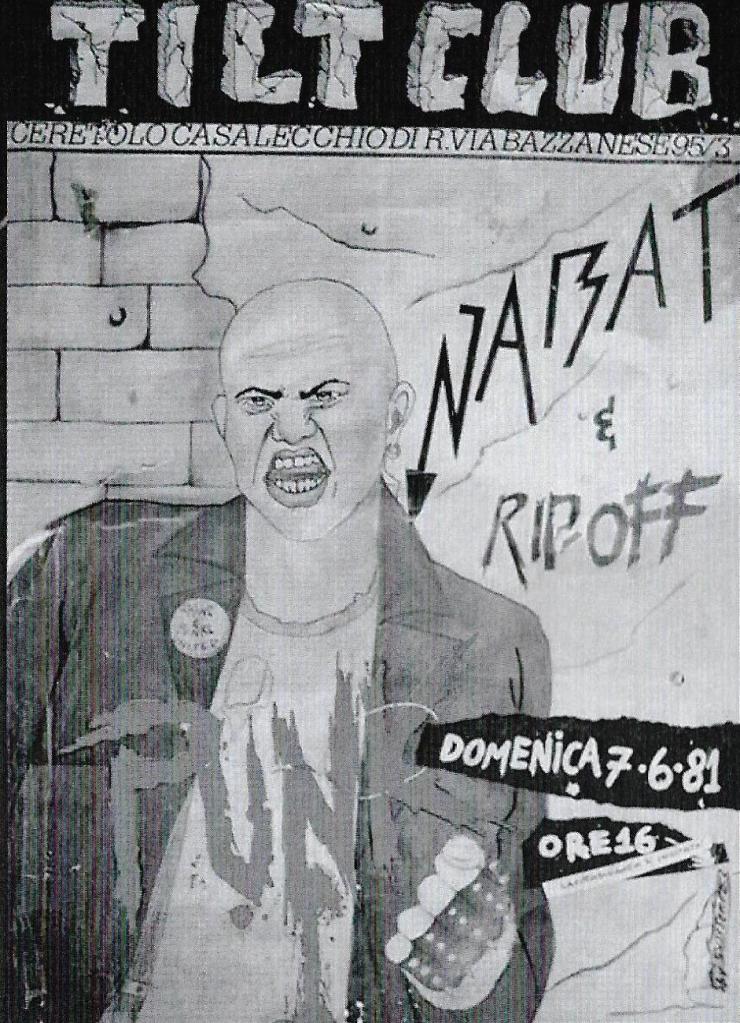

Our first gig was at the Osteria dell’Orsa [a tavern in Bologna’s historic town centre], and the second at the Tilt in Ceretolo [a small town about 10 miles west of Bologna – Editor], which I believe is now a strip bar. They were small, niche venues, but we had around a hundred punters at each show. Of course, Nabat played with us.

And how did these concerts go?

We never managed to finish a gig because the night would always end in a brawl. We loved provoking people. In Bassano, the folks from Radio Sherwood – a famous station in the Veneto region that organised concerts – invited us to play at a social centre full of feminists. I’m not sure if they were already familiar with our ‘style’, but they started chanting, “With your fingers, with your fingers, guaranteed orgasm”, and we replied, “With a dick, with a dick, it’s a whole different ball game”. Stuff like that. We even pretended to be gay… it was all just provocation. I don’t know if you’re familiar with Skiantos [a comedy punk band linked to Bologna’s ultra-left of the 70s – Editor], but naturally, they ended up calling us fascists. We didn’t care.

There’s another old Rip Off interview where you mention that your key influence was Cockney Rejects because they were football hooligans. Were you a punk when you first started hanging around the terraces? In England, football was very much a skinhead – and later casual – thing.

I started going to the stadium with my father when I was six. The first ultras groups appeared in Italy in 1969, and in Bologna in 1974. But they were quite different back then – much more fricchettoni [long-haired freaks]. Later, I stopped going for a while because I had other interests. But when I visited London, I went to watch West Ham and other teams a few times. My passion for football reignited, and it stuck with me.

When I returned to Bologna, I started an ultras group made up of skins and punks. We called it ‘Total Chaos’. But unlike the skinheads, the punks didn’t have the stamina to keep coming to the stadium – they’d only show up for the big matches. We took down the banner in 1985. Over time, the punks dropped out, and the skinheads stuck around, eventually forming their own group and merging with others. But the ‘Total Chaos’ group gave birth to smaller neighbourhood factions, like ‘Total Chaos Borgo Panigale’ and ‘Total Chaos Mazzini’.

Were you a hooligan?

Yes, though I actually started with basketball rather than football. As you know, Bologna has two important teams, both of which are as much a part of the city’s identity as the sport itself: Fortitudo and Virtus. Fortitudo is seen as the more proletarian team, and their supporters were the Forever Ultras. I used to support Virtus, but that’s mainly because it all depends on the district you’re born in. If you’re born in a certain area, like mine – Mazzini – and all your mates support a particular team, you end up supporting it too.

But anyway, we’re talking about a different time – a time when the people around me were in and out of prison, people from a certain background, and I was only 17. I’d say that was my university, where I was shaped. More like where I learned how to survive.

Do you think that football hooliganism back then, in terms of violence, was different from what it is now? Was there less police presence?

It was definitely different. The police were there, but they allowed certain things to happen. It wasn’t as controlled as it is now. Today, with all the cameras and security measures, it’s much harder to get away with anything. I saw a video yesterday where two Roma fans were shouting at the coach – the police identified them straight away and slapped a stadium ban on them.

Let’s talk about music. You recorded the famous split tape with Nabat in 1982. Can you tell me about the recording?

It was recorded in the basement where we were practicing in Via Creti, in the Bolognina quarter – with very makeshift equipment. It’s a four-track mix: one microphone for the vocals, one for the drums, one for the bass, and one for the guitar. The sound is what it is – very raw and antique-sounding, I’d say! Everything was recorded live, with all the fuck-ups you’d get in a live show.

There’s a song named ‘Skinheads’, so I imagine you had become a skinhead by that point?

We were a mixed punk/skin band like Blitz, but I was still very much a punk when I wrote that song. I’ve always written the songs myself.

But why did you write a song called ‘Skinheads’ if you weren’t one?

All my friends were skinheads. The song was for them. Like Sham 69 said, “If the kids are united, they will never be divided”. It was just a reflection of the scene at the time.

Ironically, on that split tape you sound more purely skinheadish than Nabat. They had a stronger hardcore punk influence, while yours was slower ‘neanderthal Oi’.

Well, I’ve always wanted to hit hard with few, direct words in the lyrics. Nabat was more elaborate, more refined, both musically and technically. They were much more advanced.

Since you said you wrote the songs, what were they mainly about?

The song ‘Tortura’ was about state repression at that time, both globally and in Italy. After the 1970s, the time of the Red Brigades and student riots in Italy [in 1977, a student protester was shot dead by the police in Bologna’s Mascarella Street – Editor], repression reached a point where torture almost became routine practice for the police, or at least was seen as justified. It was the same in places like Chile and Argentina. Then there was an anti-militarist song, [‘Anti Army’], an anti-police one [‘Io non voglio polizia’, meaning ‘I don’t want the police’], and we already discussed the one about how drugs are a weapon of the powerful.

Listening to the reissue album, what do you think of these recordings today?

They could have been much better – musically, at least. I’ve heard several Rip Off covers, and I really liked them. For example, ‘Droga’ was covered by The 80s, and I think it’s spectacular. They arranged it much better than we did. It could have all been done better, and I think I could have sung it better too.

When the line-up changed, the guitarist and bassist stayed. Why did you leave?

For ideological and political reasons. Look, I’m neither right-wing nor left-wing, and I won’t let myself be used by either side. For me, there’s the interests of the people, and I don’t give a damn about anything else. There came a point where people in punk started selling themselves. If I have to bend over for the local administration of Bologna to get something, like a rehearsal space, and sign up to their political platform in exchange, I’ll say no. It all goes back to the whole RAF Punk discussion. That’s why I think they were right in some ways. If I have to sell myself, give away my soul, then it’s not worth it. I’d rather struggle, go hungry, but I won’t let myself be bought in any way.

What about Rip Off’s turn to the right, though? Did that occur only when the new singer, Rozzi, entered the picture, or were those ideas already starting to take shape before then?

As you know, in the 1980s skinhead scene, there were quite a few people who leaned to the right. So, it’s fair to say that certain ideas were already floating around before the fateful turn. That was also part of the reason why I left, as did Crema, the drummer, who moved to Milan to play with Wretched [an important hardcore punk band that lived in the legendary Virus squat in Milan – Editor]. I got involved in squats in Bologna, like the one in Via Galliera, where I tried to form a band – but it didn’t work out.

So, was Rozzi a real nazi skinhead or just a provocateur?

He was just a dickhead, to be honest. Definitely not a real nazi. Stiv from Nabat might have been a true believer, but Rozzi? No way.

Were you at the infamous Certaldo festival that cemented Rip Off’s far-right reputation?

Absolutely not. I refused to go because I was very disappointed with the direction the band had taken. I stayed friends with the bass player, who sadly later died in an accident. But I never had any contact with the guitarist again. Crema, on the other hand, is still a very close friend. He lives near Ferrara but works in Bologna, so we manage to see each other at least once a month. We go for pizza together. He still plays, though I can’t recall the name of his band.

Were you surprised to hear about the stiff-arm salutes in Certaldo, or did you expect something like it to happen?

As I said, the signs were there, so it was no surprise. They were dicks.

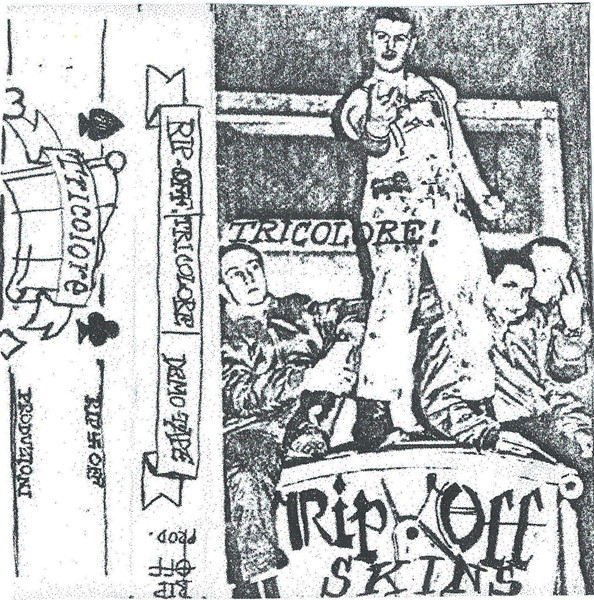

Have you heard the tape they released in 1983, Tricolore? On the back cover, there was a little swastika between the words ‘Rip’ and ‘Off’.[3]

Indeed. No, I’ve never listened to it and I’m not going to, I don’t care. After Certaldo I wanted nothing more to do with the band.

There’s an interview with Pantera from the second line-up in the bizarrely titled book Skinheads – Rock ‘n’ Roll’s Damned Ones. He says the first line-up was just a Nabat copy, while the second one is the one that really counts…

The one that played no more than two gigs? Ah well, if he says so…

He also says the band greatly improved musically, but to be honest, I can’t hear much musical difference between the two tapes… Last question: I know two original members of the band are no longer with us, but given the recent reissue, would you ever consider reforming Rip Off for a special gig?

We’ve thought about it. The drummer and the vocalist are still around. We’d need to find a bass player and a guitarist, but that wouldn’t be too hard because there are some good musicians out there. I have a few names in mind, and a guitarist friend of mine even suggested himself after he bought the reissue. But I’ll tell you, it’ll be almost impossible. Or maybe not. You never know…

Thanks very much for the interview, Sceriffo.

Many thanks to Francesca Chiari for helping to transcribe and translate the interview.

[1] The ‘nihilists’ claimed to be inspired by the Russian nihilist movement from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which followed a doctrine of political terrorism and violent crime – though as the author of the book Italia Skins, Flavio Frezza, told me in an interview, it’s unlikely that many ‘nihilist’ punks were actually into Russian nihilism. For them, it was simply a way of saying they were anarchists but not pacifists.

[2] Helena Velena, formerly known in the 80s as Jumpy Velena, was the founder of the band and anarcho-punk collective RAF Punk and later launched the label Attack Punk Records. Nowadays she is known for her interminable social media rants against “nazi-bolsheviks” (a term that seemingly covers everything from communists to fascists, with particular ire reserved for Palestine supporters and opponents of NATO). She is also a transgender and countercultural porn theorist, describing herself as a “semiotic-psychedelic guerrilla”.

[3] The songs contain mostly basic skinhead lyrics about rebellion and fighting, with nothing overtly fascist, although there is some heavy-duty rightwing posturing in the anti-immigration song ‘Via dalla nostra città’: “This is not your home / stay in your own country / you’re taking our jobs and ruining our neighbourhoods / get out of our city!” Less than 20 copies were made of Tricolore (handed out to friends and sent to fanzines), making it one of the rarest Oi artefacts. Missing from the tape – and probably lost forever – was the title track ‘Tricolore’, which the band had recorded for a compilation. Steno of Nabat rejected it, and all band members lost their tapes with the recording.