Confront your average ‘progressive’ with the term “traditional values” and they’ll shudder. But in truth, “traditional values” mean different things depending where in the world you are and who you ask. For Miners, an Oi band from the town of Bergamo in north Italy’s Lombardy region, these values are “sharing, solidarity, a sense of belonging, dignity, fun and a sense of humour” – the traditional values of the Italian working class back when it was among the strongest in Europe. Today, after three decades of Italy’s complete political liberalisation, these values have all but evaporated, they say, replaced by self-seeking individualism and resentment.

Miners were formed about a decade ago and are a powerful live proposition, but they only have two releases under their belt. Valentina Infrangibile asked them why that was, also probing on topics such as Italian vs English lyrics, clobber and being an outsider. Miners are: Albe (vocals), Fil (guitar), Tiziano (bass), Beppe (drums).

Hi there lads, thanks for taking the time for the interview. Could you tell us the story of your band so far?

Fil: Our story began outside a cinema in Bergamo in the late summer of 2011. Tiziano and I had already been friends for a long time, and after watching This is England together, I went on my knees outside the cinema and made him a fateful proposal: do you want to play with me? I already had some songs prepared in my head but no one to play with. He had just finished his previous band 501 and was a very good musician, so I really wanted him on board.

For months it was just the two of us rehearsing: me on vocals and guitar, him on drums. Then a new chap came in on bass, but he was a good drummer too. Tiziano was rusty on drums: he’d start fast and then slow down, lose his sticks, etc… so they swapped instruments. I, on the other hand, couldn’t keep up with the singing, so I asked a friend who was as deeply involved in the subculture as myself: Alberto (‘Albe’). He’s really good, so I can proudly say that I was a very good talent scout.

In September 2014, the old drummer left, and in came Beppe, who had just turned 18 at the time. Bsides bringing a certain rockiness to the rhythmic foundation, his presence also lowers the average age of the band, which is pretty advanced otherwise… The line-up hasn’t changed since then and I’m really glad about that: apart from playing together, we really are friends.

Albe: Filippo and I already knew each other through mutual friendships, while I had only seen Tiziano at a few gigs. I felt on the same wavelength with both of them right away. I met Beppe at a village party: he was only 17 years old, combat boots, shaved head, flight jacket and a SHARP patch. I couldn’t believe my eyes, and when he told me that he played the drums it was: bingo!

Let’s talk about your band name. For our English readers, the word ‘miners’ will probably evoke the Great Miners’ Strike of 1984, the resistance of working-class communities against Thatcher, maybe even the benefit gigs that Redskins and other bands played for the miners. Did you choose the name because of these connotations or did you have something more Italy-related in mind?

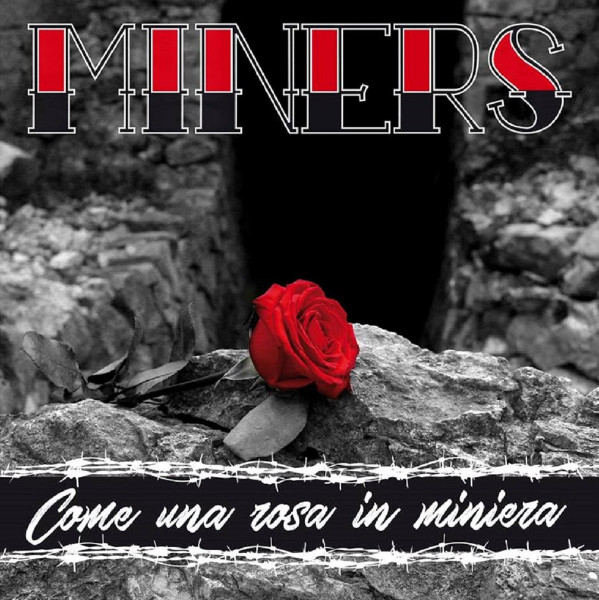

Fil: Both. Just as we were looking for a name for the group, we saw pictures of the Sardinian miners’ protests on the news and we were impressed. The mountains behind our hometown of Bergamo also hosted several mines, all of which were closed in the 80s. The pictures on the cover and on our CD, Come una rosa in miniera [Like a rose in a mine], were taken in a mine in the Bergamo valleys. Besides, I’m a fan of the 90s strand of films about the working class, and I found many similarities with our Italian experience in movies such as Brassed Off and even Billy Elliot.

Tiziano: This was precisely one of the reasons: even though we are the ‘bottom heap’, considered weak and without influence, we’re strong when we come together. United we can make a lot of noise, in England as in Sardinia.

Who writes the music and the lyrics?

Albe: It’s a collective effort. Anyone might bring an idea, a lyric or even a finished piece to the rehearsal room. Then we all work on it together. Everyone makes their contribution. But we’re not competing with each other over who contributes the most – we’re working together. I often send Tiziano some whistling or hints of music and from these, new songs magically arise.

Tell us why you named your album ‘Like a rose in a mine’, which is also one of the tracks on the album.

Tiziano: ‘Like a rose in a mine’ is open to interpretation. The rose represents the beautiful things that happen around us every day but that we, for one reason or another, can’t see: “We are ghosts, invisible to the naked eye”.

Albe: Well, the piece also tells a bit about the state of mind that some of us were in at the time: the desire for rebellion, the redundancies, jobs that couldn’t be found, union struggles. To be sure, none of us has ever worked in a mine, but somehow we’ve always been fascinated with the struggles of the miners in any part of the world from Italy to England, from South America to Belgium, against the bosses and the big multinationals: their mobilisations, their demonstrations, their street battles.

Six years have passed since the release of the album. Why such a long wait for a new release, and what have you been up to in the meantime?

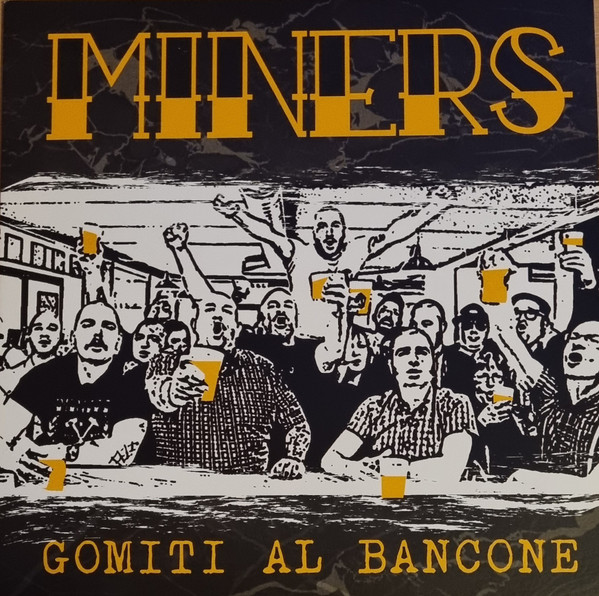

Fil: We were ready to release the Gomiti al bancone seven-inch as early as January 2020, but then Covid stopped everything. Then there were a couple of years of uncertainty between lockdowns, restrictions and stuff, so here we are with the seven-inch that was supposed to come out a long time ago… This at least is the ‘official’ version to conceal the fact that we’re lazy, and if it weren’t for Albe who keeps prodding us, we’d still be working on the demo…

Tiziano: We’re just lazy. We don’t want to release an album with predictable and banal songs just to get something out. Fortunately, at our level there’s no one to give us a deadline, but we’re on the right track and hope to have something new ready soon.

Many Italian Oi and punk bands now write lyrics in English, hoping this will open up the market for them abroad, especially at festivals across Europe. You, on the other hand, write almost exclusively in Italian. Is that important to you – and do you think Italian Oi bands should generally sing in Italian?

Fil: In all honesty, we do it this way because we like it. It gives us satisfaction and, in a small way, fills us with pride – also because we put so much effort into it.

If it gave us satisfaction to sing in English, we’d do it. Marketing tactics are of no interest to us. We like singing in Italian – the language has a powerful edge and musicality. Also, let’s face it, since it’s our mother tongue, we can express ourselves to the full. I love Italian Oi. Looking at the bands that have inspired me, they all sing in Italian, so it was a natural choice for us. I’ll tell you in advance though that I’d like to do something multilingual, like a song with verses in different languages. Hopefully sooner than in 10 years…Wake up, fellow Miners!

Albe: I’m only learning about this now… although I predict that my English is shit, we can give it a go.

Anyway, I think that the feeling of belonging to a city, a country or a region beats having international success. I like to sing in Italian and tell people something about myself, about the things I’ve lived and felt. It wouldn’t make sense to do this in English or in any other language – or rather, it wouldn’t be understood. Just to be clear, I don’t mean to disparage Italian bands that sing in English. I respect them, but I have my own personal view on this matter.

Some of you have families and children. Do you think that the skinhead lifestyle is tied to more traditional values than, for example, punk and therefore more easily reconciled with family life?

Fil: That’s a nice thought and I agree with you. Being a skin is tied to a lot of working-class values: sharing, solidarity, a sense of belonging, dignity, fun and a sense of humour. All good things in my opinion. I don’t know if a nihilist, a self-destructive person or a misanthrope would want to raise a family.

Tiziano: I think being a skinhead is much more about certain values than, as you say, punk… But maybe that’s also simply because you can count punks over 40 on one hand…

Albe: Um… I don’t know, it’s not like punks don’t have kids or families. Maybe at a certain age they no longer have mohicans or safety pins stuck all over them, so you notice them less. Either way, it’s not an obligation to bring children into the world – thank goodness!

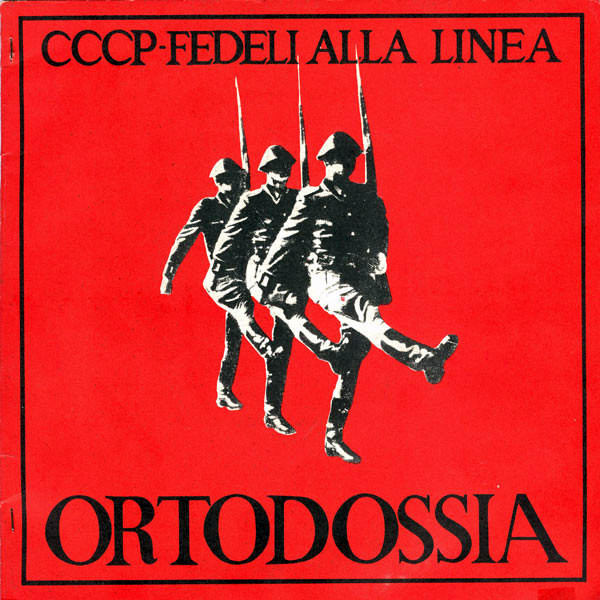

Your song ‘Non fare come noi’ contains a quotation from CCCP, namely from their enigmatic lyric ‘Morire’: “Produci consuma crepa” [Produce, consume, die]. What is your song about, and why did you quote these words?

Tiziano: CCCP have, if not shaped, then at least accompanied to some extent every teenager of our generation who has been affected by ‘alternative’ music… You have to produce, consume and eventually die to maintain the great merry-go-round called Italy. Italy, like the rest of Europe and the entire west, is based on capitalism: money, power and sex are the three dogmas on which the west is founded. What’s more, the state lives off the people’s vices, ‘drink, smoke, and drug addiction’, enriching itself through the respective monopolies.

What do you think the original CCCP lyric is about?

Tiziano: I haven’t listened to the actual CCCP song for 25 years.

So CCCP isn’t an important band for you guys?

Fil: I never liked them, so they aren’t really among my musical references. In my opinion they aren’t even punk – at least what I understand to be punk. [Disappointed to hear that – Editor]

Tiziano: Like I said earlier, I wouldn’t call CCCP ‘important’ as far as our own cultural background is concerned. There are certainly bands that had more impact on us growing up, but even so CCCP were a part of our world when we were teenagers.

Albe: CCCP weren’t essential for me either, but that line ‘produce consume die’ says it all, especially with regard to today’s society.

[CCCP, also known as CCCP – Fedeli alla linea, were a fairly amazing Italian post-punk band in 1982–90. They traded as a ‘pro-Soviet punk band’, but it’s doubtful that they were really into Communist politics rather than just enthralled with the aesthetics. In any case, with follow-up projects such as C.S.I. and PGR their vocalist Giovanni Lindo Ferretti gradually moved towards a kind of Italian neofolk as well as towards Catholicism and the political far right – Editor]

A section of your lyric ‘A te’ resonated with me since it talks a bit about how one becomes a skinhead. I’ve always had this theory that, apart from the posers, those who end up in this scene often come from a socially disadvantaged background or were bullied in some way. In short: we were outcasts and we made something of ourselves – what do you think?

Fil: I’ve got nothing to add because you’ve summed up a whole concept in a few lines. I can only add that where others did not exclude us, it was we who self-excluded ourselves from certain environments that we didn’t like and instead immersed ourselves in settings where we felt at home. Which is no small matter.

Tiziano: ‘A te’ is an autobiographical song… I was bullied as a kid, but it made me the person that I am today. The taunts, slaps and humiliation I got as a kid, for the simple reason that I didn’t dress fashionably, because I wore glasses, because I wasn’t interested in being the neighbourhood bully, in short: being different from other people gave me the self-esteem that I now put on display. I’m confident in myself, in my being a skinhead, in not being afraid to stand up to someone who weighs four of five stone more than me. The resentment, the anger that I harboured inside turned into pride and self-determination – into my being a skinhead.

Albe: I too was mocked for being chubby, though I have no idea why no one does it to me anymore now that I’m even chubbier. Fuck the bullies!

In ‘Bassa bergamasca’ you talk about your hometown, and as is so often the case, it sounds like a love-hate relationship. Tell us more?

Albe: ‘Bassa bergamasca’ came out of a desire to relate what it means to grow up in a very special part of the Bergamo region. Only someone who comes from there or has in some way experienced it can convey the sense of belonging, but at the same time the shit that is part of being here. The arrangements and contradictions in these parts are completely different compared to the city and the valleys of Bergamo. If I say, for example, that I’m from a village in the lowlands, a city dweller will immediately turn their nose up at it.

Indeed, it’s fair to say that this place doesn’t offer much and most people are argumentative and grumpy. Let’s say that I encapsulated what the Lower Bergamo area represents to me in three simple words: polenta [a north Italian dish based on boiled cornmeal], fog and porco dio [a freqent north Italian curse more or less equivalent to ‘fucking hell’].

Beppe: This is the most drug-ridden place there is.

What’s the political climate in your hometown?

Albe: Bergamo is unfortunately a city of old men, run by the clergy and governed by radical chic types who wink at the right with one eye and at the left with the other [He is referring to the liberal Democratic Party – Editor]. As for the province, apart from a few happy little islands, let’s not even go there.

The climate is that of a middle-class city that doesn’t want to see the real issues and where most people go about their fucking lives as if nothing were wrong. As I see it, everything is politics. I’m part of a political collective called ‘Spazio Jurka’ that is based in the lower Bergamo area, and we’ve done a lot of stuff on the ground: in the neighbourhoods, in the streets, in the bars where you’re confronted with all the contradictions, problems and realities of this world. With some people you can talk and discuss, whereas with others there’s no hope.

Another problem that weighs heavily is repression, which has increased more than a little in recent years. Complaints are pouring in on those who raise their voices and rebel, and the clampdown is severe. Our dear friends, the Bergamo ultras, predicted this some time ago when displaying a banner in the north stand: ‘First they’ll come for the ultras, then for everyone else’ .

There’s constant talk of the working class in your lyrics. What do you think about the state and situation of the Italian working class today, and what would you like to see happen politically?

Fil: The working class no longer exists, or at least there are only a few of us left. There are only workers now. They’ve lost the concept of class consciousness, they’ve lost the spirit of solidarity, they’ve abandoned the fight for the emancipation of the proletariat and only think of their own gain. Last but not least, they vote for the right and the far right. I work in a factory and I’m also a union delegate, so I know what I’m talking about. On top of all that, they dress very badly.

My most recurrent erotic dream is to wake up one morning and see a turnaround, both politically and socially. But then I wake up…

Albe: “Anger pride and solidarity” – I still believe in these things.

In your lyric for ‘Bootboys’ there’s a reference to Laurel Aitken. To what extent are you in touch with the reggae and ska side of the skinhead cult?

Tiziano: Some of us follow the Italian ska scene, others don’t. These are personal choices and tastes. I also used to play in a ska band and this, like everyone else’s past, enriches the arrangements of our songs.

Albe: I listen to it. I even buy the odd record or attend the odd gig, but it has never gripped me the way Oi and punk in general have. As Tiziano says, it’s a matter of taste.

Unlike with many other Italian Oi bands, especially newer ones, your dress sense is reasonably old school, with Ben Shermans and all. Is that important for you?

Fil: I love the traditional style, it makes me feel really good – it’s an act of self-love. The skinhead style is a dignified, comfortable and stylish outfit, but not ‘fancy’. As they say: hard and smart! I work in a factory and I’m dressed like a dummy in my work uniform all week. When I dress the way I want to, I feel like the king of the world.

Tiziano: Style is what sets us apart from the rest – shaved heads, polo shirts or t-shirts. It’s what distinguishes us from other subcultures. It’s not what you wear, it’s how you wear it. You can tell a poser in a Fred Perry from a skinhead immediately: you can see the pride in the skinhead’s face, their sense of belonging to a particular cult and showing this to others. Wearing, say, a Ben Sherman is like a Trojan helmet tattoo – a proud display of belonging to something.

Albe: Let’s say that Tiziano and Filippo are more sectarian, while I personally like to dabble in the clothing styles of mods, skins and casuals alike.

Anything else you’d like to say to our readers?

Fil: Get in touch with us – we’d like to play abroad, even if we’re provincial and sing in Italian.

Tiziano: This life is crazy but it’s all mine.