Güerra: Quanta fame hai? LP

(Hellnation/Radio Punk)

The first time I heard about the band Güerra (the Italian word for war, but with an extra Motörhead umlaut) was when my tattooist was inking something that contained the word ‘war’ into my skin. This prompted him to tell me about a “great band from Romagna called Güerra that sounds like Blitz”. I downloaded their first, pre-pandemic album off Bandcamp, but was only partially convinced. While it contained a few catchy tunes, many songs were sung in English and the vocalist’s accent was so strong as to be grating. I also had the impression that perhaps the band had rushed into the studio too early, i.e. before it had enough songs from which to compile a truly strong and consistent album.

When I caught them live a few times in the following months, I was much more impressed and found it regrettable that the available recordings didn’t do their powerful live shows justice. With this second platter, I’d say they’ve largely made good on the live promise and put out something more representative of where they’ve been at those past couple of years.

First off, although the band seems to have been formed on the premise “let’s do a Blitz band” one drunken night in a bar in Forly (in Italy’s northern Emilia-Romagna region), its sound wasn’t that close to Blitz even on the first album. Certainly not to the point of what you’d call ‘Blitz worship’ a la Criminal Damage or more recently MESS. It certainly was, and remains, punchy and direct Oi/street punk music, though. The tempos have picked up a bit since the first outing and the choruses are more memorable –- that’s important for Italians, who are known to sing along all the words at gigs (sometimes the first time they hear them).

Given this melodic quality, coupled with e healthy dose of street grit, I’d be tempted to describe them as something like a faster Italian Red Alert rather than Blitz. I can also hear elements of Cock Sparrer (though not in a cliched way), Angelic Upstarts and Banda Bassotti, all of which are acknowledged influences – but also Machine Gun Etiquette-era Damned. If there’s any distinctly Blitz sounds, they most closely resemble The Killing Dream, a neglected minor work that I always liked –- for example in the guitar stylings at the beginning of ‘Branco’. Occasionally, there are excursions into other genres, as in the jungle-drum backed psychobilly breakdown of ‘Spranga’. It all sounds very Italian, though – probably much more so to my ears than to theirs. And that’s a good thing, too.

Speaking of which, this time around all songs apart from two are sung in Italian –- a wise decision. Not only does vocalist Mattia sound much better this way, the choice is also consistent with our long-standing campaign for bands to sing in their own language. “Over time”, Mattia tells me, “we realised that the English language was a limitation, if not detrimental to our songs. Some ideas can be explosive when you express them in your mother tongue –- but when you translate them, they can end up sounding banal”. Hear, hear.

On the couple of occasions when he does sing English, the effect is fatal indeed. Performed in Italian, ‘Riot’ could have been an anthem along the lines of Plastic Surgery’s ‘Rivolta’, and ‘Knots’ could have been a great punk tune somewhere between The Damned, The Blood and Dwarves. But neither of them is what they could have been because the poor English pronunciation distracts from the music and message. To me, this is the only weak point of what’s otherwise an album that the band, and in fact the whole scene of the Emilia-Romagna region, can be proud of.

What are the lyrics about, then? Songs such as ‘Branco’ (The herd) and the glam-rock guitar driven ‘Condannato a vita’ (Condemned to live) speak about the excluded and the underdog, about those who live on the margins, but also about that great majority of us who are “free to die of work or die from hunger”, as the song ‘Io vivi’ (I live) recalls. ‘Cigarette storte’ (Crooked cigarettes) and ‘Quello schifo di bar’ (That lousy bar) are about those who stoically go their own way as times change and old certainties evaporate into thin air. Or rather: are bulldozed out of the way by the nice liberal Democratic Party, as happened to Bologna’s much-loved community centre XM24, whose demise the song ‘Artax’ bemoans. There’s a Covid-quarantine inspired track (‘Knots’), while elsewhere there’s talk of police brutality and ulimately the need to revolt (‘13:12’ and ‘Riot’).

The album was recorded during two sessions at the Bologna’s Oi-est recording studio and rehearsal space, Vecchio Son, which is run by Steno of Euro-Oi legends Nabat, and ably mixed and mastered by resident sound engineer Grug. It has a strong consistency to it that the debut lacked, and as far as I’m concerned there’s no filler. “We had a pandemic in between to think about our second album, so we weren’t short of time and ideas”, confirms Mattia –- “so hopefully it’s a good sequel like Aliens is with respect to the first film”. For my taste, it’s a better sequel, just as Aliens was to Alien.

Although the friendship of the band members began some two decades ago in the small town of Forlimpopoli, a small town and kind of nerve centre of the misfits from the area, today they’re scattered across Romagna. This means that some of them were worse affected the catastrophic floods that recently afflicted the region than others. As I write these lines, Mattia is still busy shovelling mud out of his flat – Güerra’s drummer, meanwhile, has lost everything. You can’t rely on the Italian state in such situations, but groups such as Bologna FC’s ultras (Forever Ultras) and the Active Solidarity Brigades have been doing great work to alleviate the situation, collecting and delivering food, helping on location shovel in hand, etc. It’s a disaster, but here’s hoping the indefatigable Romagnan fighting and community spirit that also runs through Güerra’s album will help our friends to get over the worst. Te bota Romagna!

To turn to something completely different. Güerra – war – is not only the name of the band, Guerra is also the actual surname of their vocalist Mattia. For this reason, I decided to send him a few questions exclusively on the subject of war. Note that this isn’t a proper interview, just a one-off email exchange – hence its ‘questionnaire’ character.

Matt Crombieboy

Your surname is Guerra. Is this the only reason why you chose the band name Güerra?

Mattia: Yes, Guerra is my surname but that’s not the only reason we chose it. “War” is a strong and powerful word and, for various reasons, very frequent in the common vocabulary. We liked the name immediately. To us, it means many things: for example, it refers to the reaction of an oppressed class to the ruling class; work-related deaths to starvation wages (to quote the legendary Italian hardcore punk band Contrasto: “isn’t this war?”), In short, war understood as ‘class struggle’ and not as territorial bullying for expansionist purposes by the ruling class at the expense of the poor.

We don’t like war and we would never be soldiers, except if the barrels of the rifles were facing the other way. The covers of our records reflect this concept. Apart from this, I attach a personal meaning to the term war: everyone wages their own battles, a personal war – often alone or with the feeling of being alone. Not long before we started playing together again under the name Güerra, a friend of ours took his own life, and the song ‘Lettera ad un amico’ (Letter to a friend) on the first album is about him. The word war is very closely linked to this too: to those who fight their own battles, which, unfortunately, are sometimes lost.

The Roman author Publius Vegetius Renatus wrote in his work On Military Matters: ‘Si vis pacem, para bellum’ – If you want peace, prepare for war. Do you agree?

Sounds like crazy bullshit to me, but at the same time I think that there can’t be a world without war, a humankind without war. The history of our planet records an infinite number of conflicts and wars. One could very plausibly argue that there has never been a day without a war since man decided to fence off a piece of land and declare it his own. There has been, and always will be, someone who will want that piece of land fenced off. So in my opinion, it’s not a question of preparing for war in order to have peace afterwards, but to understand that peace is a very complex concept. Just because there aren’t two armies fighting in the open field at a given time doesn’t necessarily mean that we live in a state of peace.

‘No war but the class war’ – agree?

Well, after everything I said earlier, I totally agree.

‘The people have the right to bear arms and defend themselves’ – agree?

Defend themselves against whom? If we enter the realm of self-defence, self-protection and suchlike, the question is complicated. If you mean defend themselves against the ruling class, well, then the answer is the same as to the last question.

The Prussian military theoretician Carl von Clausewitz wrote: ‘War is nothing but the continuation of politics by other means’. Do you agree?

War is de facto another way of doing politics. When words are not enough, we turn to deeds. Like in a brawl. At the end of the day, war is a giant brawl where everyone takes a beating. Mind you, in a brawl it’s me doing it personally, and it’s my own face that will be smashed, my own skull cracked. Politicians, officers, generals and heads of state let the poor do the brawling and at best lose their reputation. But even that is not always the case: sometimes they get the Nobel Peace Prize.

Which war interests you most from a historical point of view?

It goes almost without saying that our resistance and Italy’s war of liberation from nazism and fascism interests me most, because that is our history and the memory is still alive. Having had the opportunity to meet and talk to some of those who picked up a rifle between ’43 and ’45 and risked everything to kick the fascists’ and nazis’ arses is certainly an important element in answering your question.

The driving force behind the whole history of the twentieth century and hence of what we are living through even now is definitely World War I, though. It’s amazing to study and understand the mechanisms that brought Europe and the world to collapse, just as it’s shocking to understand how that huge bloodbath unfolded.

Who of the following was the greatest military leader:

1) Julius Caesar (Gallic Wars)

2) Hannibal (Second Punic War)

3) Napoleon Bonaparte (Napoleonic Wars 1803-1815)

5) Leon Trotsky (Russian Civil War 1917-1922)

6) Georgiy Zhukov (Great Patriotic War 1941-1945)

(If none of the above, nominate your own)

I couldn’t give you a name, partly because I’m not a military historian and I don’t know much about war strategy. In any case, I do not consider people who have tried to conquer the world with weapons, killing and raping and robbing whatever they found on their way to be great military leaders.

[I later asked Mattia to clarify – the latter sentence was meant to be a general statement, not a comment specifically on any of the names I cited – MC]

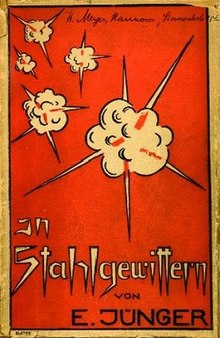

Which is the greatest war novel – All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque or Storm of Steel by Ernst Jünger?

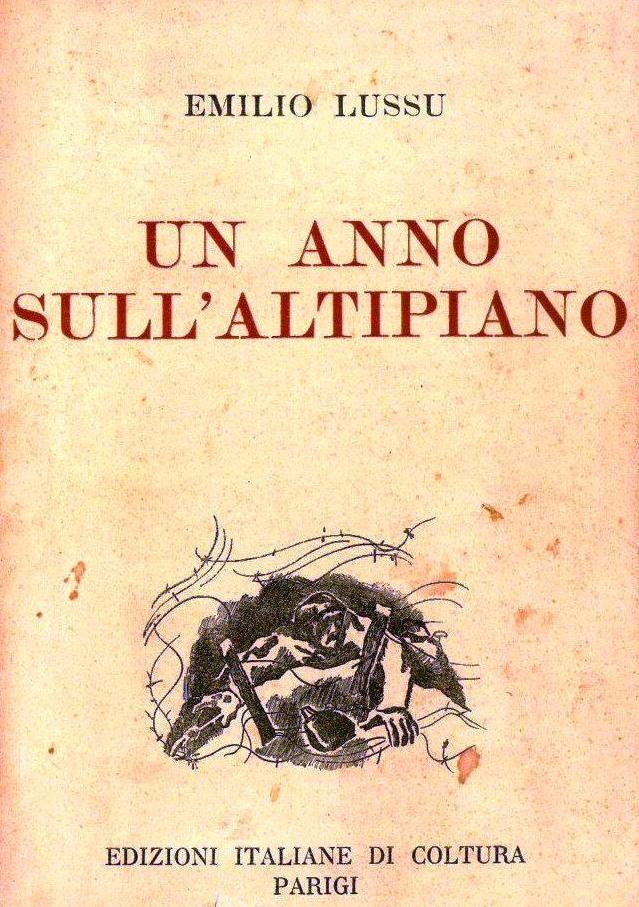

Which is the greatest war novel is not for me to say and I’ll be honest, I’m an ignoramus because I haven’t read the books you mentioned. But if I had to recommend one that I really liked and that affected me, regarding the cruelty, and irrationality of the First World War and of trench warfare in particular, where millions of poor wretches, commanded by their generals and officers glorifying the fatherland, died for a handful of stones along with millions of other poor wretches speaking a language different from their own, it would definitely be A Soldier On the Southern Front (Un anno sull’Altipiano, 1938), the classic Italian World War I memoir by Emilio Lussu.

And your favourite war movie?

The book I just mentioned was later made into a movie by Francesco Rosi, scripted by maestro Tonino Guerra (also from Romagna and with a surname to match) and starring the great Gian Maria Volonté. The film is called Many Wars Ago (Uomini contro,1970) and it’s also one of my favourite films, so everything falls into place. Here’s a quote from it: “Enough of this war of starving against starving – the enemy stands behind us”.

Should the professional army be replaced by a popular militia with general conscription?

What’s the point? A popular militia is supposed to make revolution. But times are long gone, capitalism has won. As far as I am concerned, the army should not exist at all.

‘Stop the war’ – yes or no?

Agree if you mean war in the present sense of the term. Disagree if you mean class war.

Some people see life as a war, others as a game. Which type are you?

In the days when we lost our friend Martino, Enrico and I sat on the pavement and said to each other that life has no meaning, and I still don’t think it does. But no matter how cruel it may be, we must not stop trying to laugh about it, no matter what – how boring would it be if we didn’t? So yeah, it’s both.