It’s fair to say you’ve made it in your writing career when your books are as anticipated as those of John King (The Football Factory), who as the saying goes needs no introduction to any sussed reader (though this is a good start). London Country (London Books, 2023) is a familiar canter through King’s authorly hinterland of West London (“Herbert Manor”), not only spliced and infused with more punk references than you could shake a mic stand at but revisiting three of his most popular and successful ‘cycle’ novels, Human Punk, White Trash and Skinheads.

London Country centres on familiar characters from those earlier novels, their personal crises and brushes with the judicial system, collapsing healthcare and occasionally boss sounds on tape and vinyl. Readers will be pleased to know that skinhead cabbie Hawkins makes an appearance amid the ruminations on the state of the nation, as Brexit hurtles from pinstriped gentlemen’s clubs and electoral fringe politics into daily life (King was once a leading light in the ‘Lexit’ No2EU coalition of trade unionists). Working class history writer and original skinhead Martin Knight was on hand to hear more.

MARTIN KNIGHT – I thoroughly enjoyed London Country. It has been a while coming, but well worth the wait. It returns to the physical landscapes of Human Punk, White Trash and Skinheads. Why do you focus on this area again to tell your story?

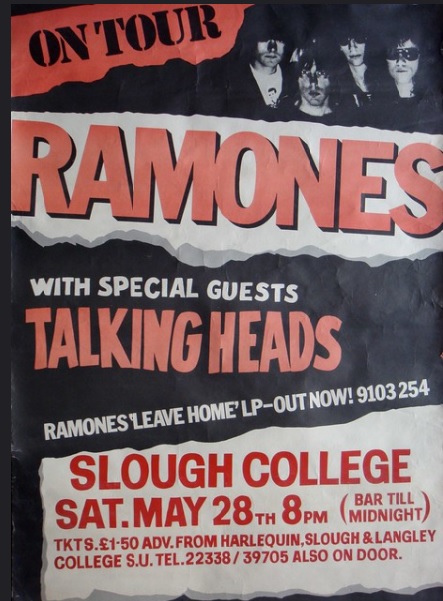

JOHN KING – At first it was due to the characters I decided to use, which made me think more about those earlier novels and what I had been trying to say in them, which in turn tapped into that post-referendum notion of London being separate and superior to the rest of England, that the city barely exists outside the inner core, and stops dead at the M25. I am talking about the section of London that is rich and elitist, thinks of location in terms of profit and prestige rather than family and culture. So my focus on the landscape of those Satellite novels returned and kept expanding in my mind and throughout the book. I grew up around Uxbridge and Slough, so there was always the pull to return to it in my fiction. Once I got started it all felt natural and fell into place.

I have always been interested in London, the older areas and traditions, but also the suburbs, new towns and satellites, the fields and woods in between, this merging of urban and rural. Generations of Londoners moved out and created these big suburban populations where the youth cultures of our younger days flourished, a vibrancy I have always loved. This movement of people was largely because of the bombing of the Second World War, but before that due to poverty and the need for better housing, which led to a rapid expansion, and over the last few decades by gentrification.

I used to spend ages waiting for those green double-deckers to arrive. They changed from red to green in Uxbridge Bus Station. Same buses, just a different colour, and their name – London Country – summed it up, even back then when I was a kid.

The book revisits some of the characters from the novels mentioned above. Was it hard to ‘grow them older’ if you see what I mean?

I started writing London Country using a new character, but quickly realised that everything I was thinking to say linked into those earlier books and people, so it was very easy taking them on from their younger selves. Events change us, obviously, but on a deeper level I think we remain the same. The problems we face are similar, and same stories play out across the age groups. I soon knew where Joe, Ruby and Ray were heading. There is a continuity there, which makes sense to me.

Ray English talks a lot about the EU in Skinheads, which was published in 2008, so I wanted to show him before the vote, just after it when he is so happy, and then later when there were those attempts to have a second referendum and Parliament was refusing to enact the decision. This remains in the background in London Country, as I didn’t want to rewrite The Liberal Politics Of Adolf Hitler, but it captures the anger Ray carries around inside him, all the unfairness and marginalisation he has felt since he was a boy.

I grew up listening to the Sex Pistols, The Clash, The Lurkers, The Ruts and the original punk bands, and I’m interested in the side of punk that spiralled off, followed its early links to dub and reggae, and through that trip hop, so Human Punk’s Joe Martin is as well. That was another no brain brainer. It all felt right once it came together. And of course there is Ruby and the way a large chunk of the population is insulted, nothing it does ever right. She brings everyone together as this spirit-like presence. At least that is the intention.

The novel is set in the winter of 2015, the spring of 2017 and the summer of 2019. Any particular reason? Were you avoiding the pandemic and the post-pandemic age?

Not consciously, no, as I had the book in my mind before covid, but I am completing the seasons and two-year jumps with my novella Grand Union, which will be part of Seal Club 2: The View From Poacher’s Hill and is set in the autumn of 2021, so that has to take the pandemic into consideration. Those first three Satellite novels were set between 1969 and 2008, and I wanted to take things on, chose the period 2015 to 2019 as it is interesting politically and socially, with enough distance from Skinheads. The sheer poison that had been directed at the masses in recent years is truly shocking, even if we always knew the hatred was there. Jonathan Jeffreys from White Trash is the personification of this. Again, it all fitted together.

We see the character Joe Martin travelling around the M25 buying records. Can you explain this day in his life and also his interest in sampling?

It was partly a device to move Joe through the outskirts of London, using the M25 to take him from Slough into Surrey and then through Kent to Essex, with a couple of stops in Stevenage and Luton on the return leg before Southall and finally Denham. Joe buys and sells records for a living, and the stars have aligned. Each of those people he visits represents an element of London Town. Their families have drifted out and their music reflects their ages and personalities.

Joe’s interest in sampling comes from buying DJ Shadow’s Endtroducing and later seeing him play in Kentish Town. I saw Shadow play twice there, and the first show in particular blew me away. Joe invests in an MPC2500 and trawls his records, has these huge collages forming in his mind, collisions of all the differences London has to offer. The sampler is a way of taking the past and creating a present, which is what we are doing all the time in everyday life. So this London Country I am trying to show isn’t stuck in the past or anything, it is alive and developing, just has its own foundations.

It was a thrill to me that Joe stumbles on one of my old characters Barry Desmond. You have been obsessed with this character and his covert personal habit for some years now. Can you explain why?

I have always been a big fan of Barry Desmond Is A Wanker, as you know. And of course, I have been urging you to write the follow-up for quite a few years now. It is a novel that mixes sadness and humour so brilliantly. It is a great overview of life. I got impatient waiting so thought I would visit Barry – with your permission, obviously – and it was a joy to meet him again. I am hoping that it will give you the nudge to pen a proper follow up. We need more Barry Desmond in our lives.

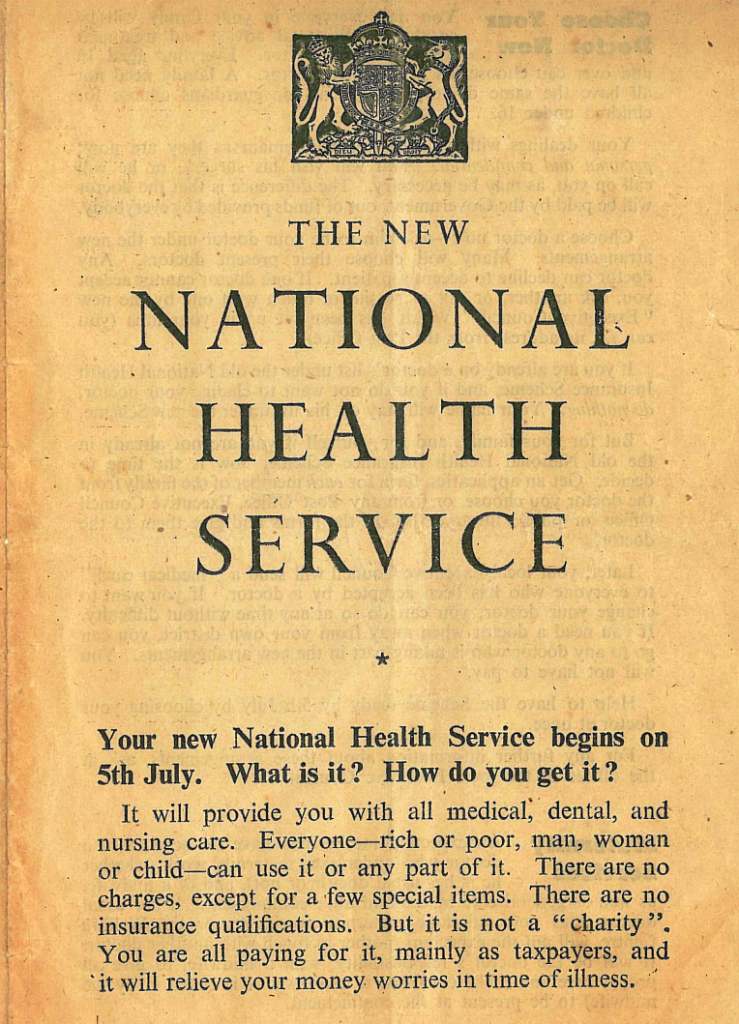

Ruby is the heroine from White Trash, a novel you described as a defence of the National Health Service in a Nursing Times interview. How have things changed for her and the NHS in this novel? Would Ruby be on strike now?

Ruby would be on strike, but reluctantly, like all the nurses. She would have thought about it long and hard, and be doing it for the future of the NHS as much as herself. I am a firm believer in the principles behind the NHS and indeed the post-war welfare state, which has been gradually dismantled since the 1980s. I believe in strong trade unions, as we would have nothing without them. A dynamic mixed economy with proper support and incentives for small businesses.

I would renationalise the Post Office, British Rail and other key industries if it was up to me. Manage them in the right way. I am a patriot and the country is its people. I don’t want these things run on the cheap, sold off to faceless companies who will bleed them dry. The NHS has often struggled during my lifetime, but with the after effects of the lockdowns things are clearly in a bad state, and it is under constant threat from those who want to privatise it, so things have got worse since White Trash was published, I’m afraid. But Ruby remains as committed as ever.

Then from Skinheads there is Ray English and his uncle Terry, the characters I most identify with, and Nutty Ray is once again walking on the edge. In later middle age they remain true to the original skinhead culture. Do you think there are many like Ray and Terry still out there?

There are hundreds of thousands of skinheads of all ages out there staying true to the culture. It is a way of life, after all. Skinhead and maybe more so the mod look is always with us. It is the classic English style. But it is as much about a pride in self, family and culture. Having a work ethic. Core British values. Skinhead came out of what went before, and it continues into what has followed.

Ray is in a constant battle to stay on the straight and narrow, as you say, to not deviate and go over the edge. He has this anger inside him, which many of us males feel. Terry is a more relaxed character, which again reflects his youth and the music he grew up listening to, and which he loves to this day. These two have been shaped by their teenage years – the 1960s and 1980s. The music captures those eras, whether it is the mellow sounds of ska, or the strident lyrics of Oi.

While Joe has gone off on a trip-hop path, Ray remains dedicated to Oi with a selection of bands mentioned. Can you tell us about some of these? Is Oi still popular today?

There are some fantastic bands around at the moment and along with my partner Andy Chesham at Human Punk, the nights we run at the 100 Club on Oxford Street, we have been putting some of them on for nearly ten years now. I am thinking about Knock Off, Crown Court, Tear Up and LOAD. Originals such as The Last Resort, Cockney Rejects, Infa-Riot and Gonads, bands who have been recording and performing new material, been on top of their game. The Angry Agenda, Arch Rivals, Hard Wax. It is a long list.

We have done a couple of Business nights following the tragic passing of Micky Fitz, and the Old Firm Casuals have played for us several times as well. We have put on Sham 69 on three occasions now. A lot of Oi’s good health is due to people from overseas, labels such as Randale in Germany and Pirates Press in the US. Lars Frederiksen has been a big supporter of the music. Oi is very underground here, but much bigger abroad. It has boomed in the US and Europe and travelled across the planet. That is pretty special, especially as it came from such a focused place. Look at the international pull of Cock Sparrer. They are bigger than most of the more mainstream punk bands.

I couldn’t help feeling that London Country is an exploration and a part eulogy even to a London that is fast slipping away – do you agree?

In a sense, yes, but it is also meant to show how London continues its older traditions in new locations and in evolving ways. It is the difference between the London that exists in place and the London that exists within people, and that is where the culture lives on in my view. London has always been expanding and changing, but of course that place we knew when we were young has largely gone, with globalisation and the focus on money-making. It is exciting in fresh ways, obviously, but very different.

I plan to write a novel called London Town to go with London Country eventually. It will be set on the four sides and centre of the city, run from the late 1800s up until the 1970s, maybe the early eighties. I will loosely draw on family history. The ghosts of people who lived in Whitechapel, Silvertown and East Ham before moving to the newly built West London. My grandfather came from Somers Town. There was a great grandfather who walked out of the house one day and vanished, and I am going to have him settle in the lavender fields in Battersea where he lives on forever.

My dad grew up in Hounslow and I want to write about the Tankerville pub that sold the cheapest cider in the area, the piano he played in a Brentford pub for beer, seeing the soldiers coming back from the war down the Great West Road when he was a boy. Tales to try and weave together. And I want to record an album or albums to go with it, use some traditional songs and mix them with the new. There’s lots to do.

Several of your books have been explorations of youth cults such as skinheads, punks, football fans etc. Do you think that there are mainstream youth cults today and will they remain as potent to the young when they get older as the ones we lived through are to us now?

Youth cults don’t exist in the same way as they did when we were kids, but it must be a good time to be young with lots of music about, and I am sure that will last people, but it does feel different, more transient somehow. Even so, imagine being a teenager today. How easy it would be for us to get credit. To have money. Being able to meet girls online rather than trying to spot one in dodgy pubs full of geezers. The general availability of everything. Don’t get me wrong, we were incredibly lucky to grow up when we did, and I wouldn’t change it for anything.

There must be a limit to the forms of music and styles of dress, and it feels to me as if most of that was crammed into a period running roughly from the mid-sixties to early-eighties, with the seventies the best decade ever. Life was rough and ready, but it was so exciting. Mind you, every generation probably says the same. I’m not a nostalgic person, tend to look forward rather than back. The past is what makes the present and future, so it is with us all the time.

Mediums and the Spiritual Church dip in and out of London Country. Do you feel that mediums and spiritualists really make contact with our lost loved ones, or do you think they merely provide a useful crutch to the bereft and despairing among us?

I don’t know for sure, but I have had some experiences that make me feel there is something there, plus we had and still have a Spiritualist streak in our family. My dad’s family were Spiritualists after the First World War, when a lot of people were attending. The country was in mourning, remember. My grandmother was a regular and practised psychometry. My Auntie Lucy was a medium. When my dad died, I was surprised I had a belief, as I was never formally raised with a religion, even if I’m culturally Christian. Even if it is a useful crutch, I don’t care, as we need to believe in something. Or at least I do. But I do feel there is an afterlife of some sort, and if I was pushed I would say that I do have some sort of belief in Spiritualism.

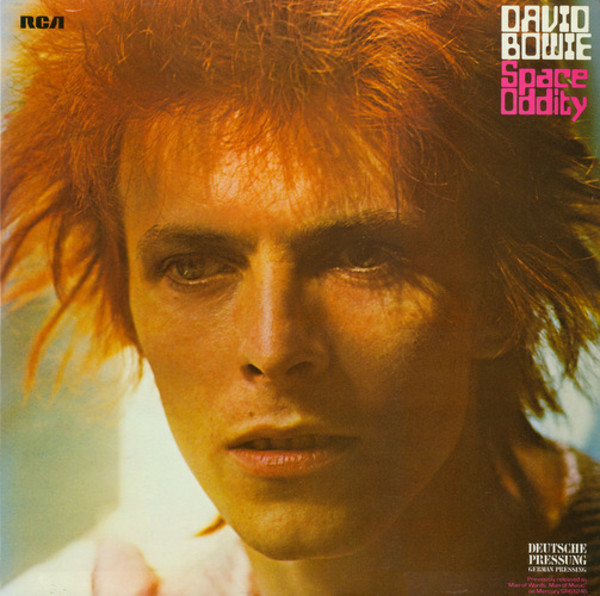

There is a quote by George Orwell at the front of Human Punk, and Orwell is a favourite of Ray in Skinheads and talked about again in London Country. David Bowie is also present in this book and Human Punk. Do you think Orwell still resonates with younger readers and what is it about Bowie beyond his music that you feel makes him so relevant today?

George Orwell is with us every day – 2+2=5. I think younger readers still look to his novels Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm, plus some of his essays. The thing that the likes of Orwell, Aldous Huxley and Ray Bradbury didn’t predict is the internet. There had always been propaganda, but it was easier to keep it at arm’s length in the past, but today there is this constant barrage that is always with people through their phones and laptops.

Orwell’s predictions on the distortion of truth have gone into overdrive. Huxley wrote about the dangers of genetic engineering and Bradbury about the destruction of literature. It is all happening. Novels such as The Circle by Dave Eggers and The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi are brilliant works by two contemporary authors who have carried on their traditions in a modern context.

David Bowie’s music remains popular, but I think what makes him relevant is its variation, the way he constructed his songs. He created these great sonic collages, which I see mirrored in hip hop and trip hop, the former such a huge musical force these last three or four decades. There is a superficial layer applied to Bowie, but dig beyond the eyeliner and he is all about time and how it passes, space and the nature of life, attempts at seeing into the future, a free-thinking spirituality. Like Orwell, I think of Bowie as very English, belonging to the new towns and satellites – a couple of future legends. Nineteen Eighty-Four meets Diamond Dogs.

Ray describes himself as “gammon”, the latest insult directed at the white, working-class male. Why do you think white working-class males are reviled so much and why are literary defences and representations of them so thin on the ground?

I think it goes back to the idea of The Mob, the unruly masses who could riot and challenge the status quo, so there had always been the need to demonise that element of the population. It has the physical strength and numbers to overthrow the rich and powerful. In more recent times, these males have become an easy target for the keyboard bigots. The sneaks and snides. I think anyone who dismisses someone because they are a white, working-class male is racist, classist and sexist. The numpties like to drop in middle-aged or old as well, when the chance presents itself, so they are ageist, which is gutter prejudice. When it comes to literature, well, publishing is controlled by a certain sort of person. There’s little chance of being treated fairly there, and especially over the last ten years or so, with mainstream publishing becoming more narrow-minded and snobbier,

I thought how you brought together the themes of gammon, Brexit, Trump etc was very bold. Many writers steer clear. Even though the people spoke over Brexit and electing “populist” leaders both sides of the Atlantic it’s looking like The Great Reversal is in full swing. How do you see the political landscape settling over the next decade?

There have been revolts against globalisation coming from the different sides of the political divide – here there was Jeremy Corbyn and Boris Johnson, in the US Bernie Saunders and Donald Trump – and due to mixtures of their own failings and establishment attacks they have been more or less sidelined. I think the political landscape will return to how it was, with a gradual eroding of democracy behind closed doors, a move towards a technocratic system, the centralising of power.

The corporations want this and the war in Ukraine and the growth of China is going to blur the lines of resistance. I can see us going back into the EU within twenty years, adopting the euro, the nations of Europe dismantled and a new empire / state created. In time this might well link with the USA. And one day maybe even with China. World government is the goal, after all. It is pretty depressing, and too many people seem more interested in petty grievances than confronting the bigger realities.

What is your view on the so-called culture wars? Does this affect what and how you write? Are you self-censoring – because plenty are and who can blame them – and do you think the pendulum will ever swing back? Do you think The Football Factory would get published today if it was a new submission?

That war has always been there during our lifetimes, but it has been given a name now, which has stuck lots of different views into smaller and smaller boxes, which makes people less tolerant than ever. Maybe not in real life, but in cyberspace, which seems to persuade those in positions of power to act in bizarre ways. So the divide does exist and it is getting worse. The internet and especially social media have played a huge part in the dumbing-down process. It works all ways, though, as dismissing anything you don’t like as ‘woke’ is as woke as woke.

I don’t self-censor and it doesn’t affect how I write, but I do bring these divisions into my work, and I have been doing that since my first novel The Football Factory. And I do blame people who self-censor. If you are going to do that, then in my view you really shouldn’t be writing serious fiction.

There are some fine writers out there waiting to be brought into print, but publishing is becoming less relevant. There are nicely designed books being released, and obviously some talented new authors, but most of the fiction that makes it through the filters of class and political correctness is directed at a tiny readership. English fiction is having the life sucked out of it, which goes back to who controls the means of production. There is little real diversity that I can see. The accountants are in control, but publishing is meant to be better than that. Without doubt there is increasing censorship, a pressure to conform and follow orders, to do as you are told.

Will things change? I like to think so, as there are some great independents out there, but it’s a battle. Would The Football Factory get published today? Not by a mainstream publisher it wouldn’t. No chance. It was hard enough when it came out in 1996, but I was lucky as I had Robin Robertson as an editor. He broke the mould. A great man responsible for giving us the likes of Irvine Welsh and Alan Warner. Seeing publishers fiddling with classic works of literature shows how low this has all sunk. I mean, who are these people? The arrogance. An author’s words should never be decided by someone else.

You have a new novella coming up in London Books’ Seal Club 2: The View From Poacher’s Hill. I’ve not seen it yet. Can you give any pointers on what to expect.

It is called Grand Union and centres around several characters from the novella in the first of the Seal Club books, The Beasts Of Brussels. It includes Ray and Terry from London Country and Skinheads, but the main focus is lorry driver Merlin, who gives up driving when the first lockdown starts, travels the canals on his narrowboat. He has a goat called Gary and isn’t going to leave him behind. We also have Stan, Darren and Matt from the first novella. A football meet is organised for when Merlin and Gary arrive in Uxbridge. The beer is flowing. What could possibly go wrong?

Can we expect another novel that follows these London Country characters into their senior years? Drawing pensions, facing up to their mortality, disrupting life in sheltered accommodation and suchlike.

It would be too sad writing about them getting old and one day falling ill. I always found Last Of The Summer Wine depressing. Even the theme song for Whatever Happened To The Likely Lads made me feel sad. The battle we all face is trying to pretend we aren’t going to die, so I would find it hard charting their decay. Writing Slaughterhouse Prayer was tough enough. I have obviously written about older characters before, but following these ones to the end would be too much.

I want to dip in and out of my short stories for a while, get a collection together as I have a lot of them sitting on my laptop, and I would like to write another book set in the future, a follow-up to The Liberal Politics, or at least something similar. That was the most fun I have ever had doing a novel. Some non-fiction as well. Make some music. Think about those collages Joe Martin talks about in London Country. Some lyrics for an Oi album. Finish off The Prison House album. There’s lots to do.

- London Country is published by London Books on May 1st, 2023.

- John King – https://www.john-king-author.co.uk/

- Martin Knight – https://www.london-books.co.uk/martin-knight

Intro: Andrew Stevens

Great read, thanks for that. I don’t read much ficton, but John King is one of the authors I make an exception for.

LikeLike